Reviews

Ping Zhu’s illustrations, with their distorted perspective, cartoonish drawings, and expansive, colorful stretches of empty space, would grab the attention of a four to nine year old, the age group that both picture books and easy readers target.

Alzanaur’s story celebrates the beauty of strangeness, affirming a truth every child (and adult) instinctively knows, and Ping Zhu’s illustrations make that beauty fully present to the reader in her captivating depictions of children, books, and birds of several kinds.

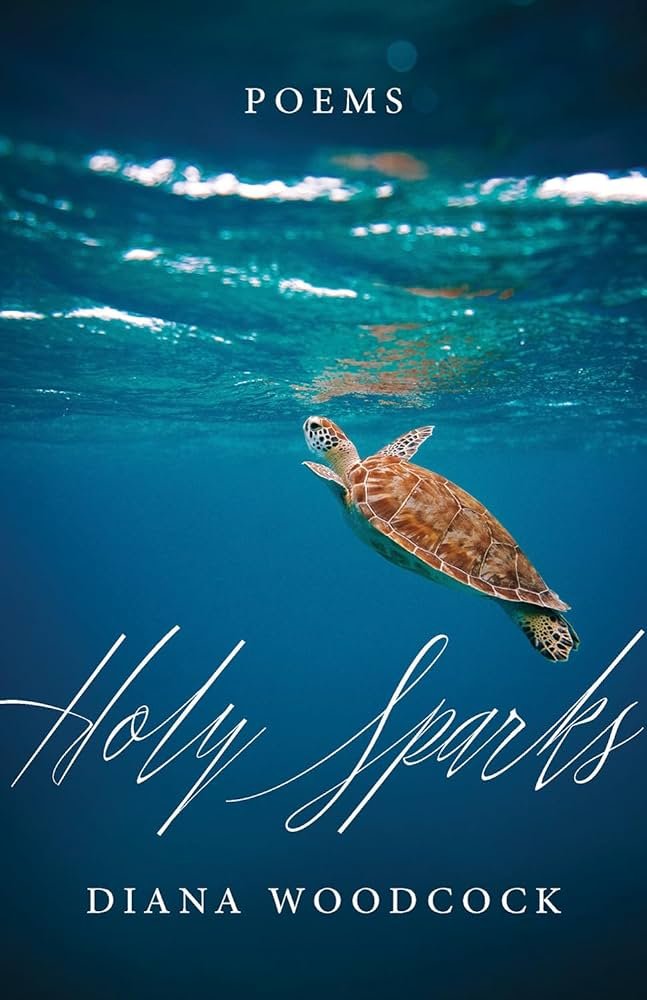

My favorite poetry texts of 2020 offered places to burrow into comfort without entering echo chambers. They charged through the overgrowth, clearing any number of paths I wished to take—through rage, sorrow, and desire to somewhere resembling peace and affirmation.

Charity Gingerich's debut collection of poetry is a case study in rhythms. The poems are filled to bursting with landscapes and choral hymns, while the poet's own internal rhythms pulse and hum just below the surface. The tension between these interior and exterior worlds, and the struggle to keep their rhythms in sync, form the emotional core of After June.

I have recommended this book to so many people for two reasons: Peterson’s reclamation of evangelical ideas, and her advocacy of women. She unblinkingly tackles evangelical failings: race, sexuality, indigenous rights, and poverty, to name a few.

Somewhere along the way, we have come to believe that a poet’s natural habitat is a coffee shop where—maintained and caffeinated by well-trained baristas—he can brood in private and pace his mind in tiny circles without breaking free to harm the general populace. So when Mr. Webster came to town, it seemed only fitting—however stereotypical—to meet him where he might feel most at home and discuss his latest poem: “The Solemn Sea.”

Wolfe elicits the praise of other novelists because he wields the powers they prize most, both as readers and fellow craftspeople: subtlety, complexity, a virtuosic handling of language, all married to a control that focuses the laser of his genius into the cutting of something greater than the sum of its parts. I suspect writers of speculative fiction love him with a special love because he is both the instantiation and justification of their much-maligned subculture.

The Book of Kells, winner of Poetry by the Sea’s 2018 Best Book Award, by acclaimed poet Barbara Crooker is her most luminous, multi-layered collection yet. Granted two writing fellowships at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Annaghmarkerrig, Ireland, Crooker spent time there researching, observing, and writing about the ancient, illuminated manuscript.

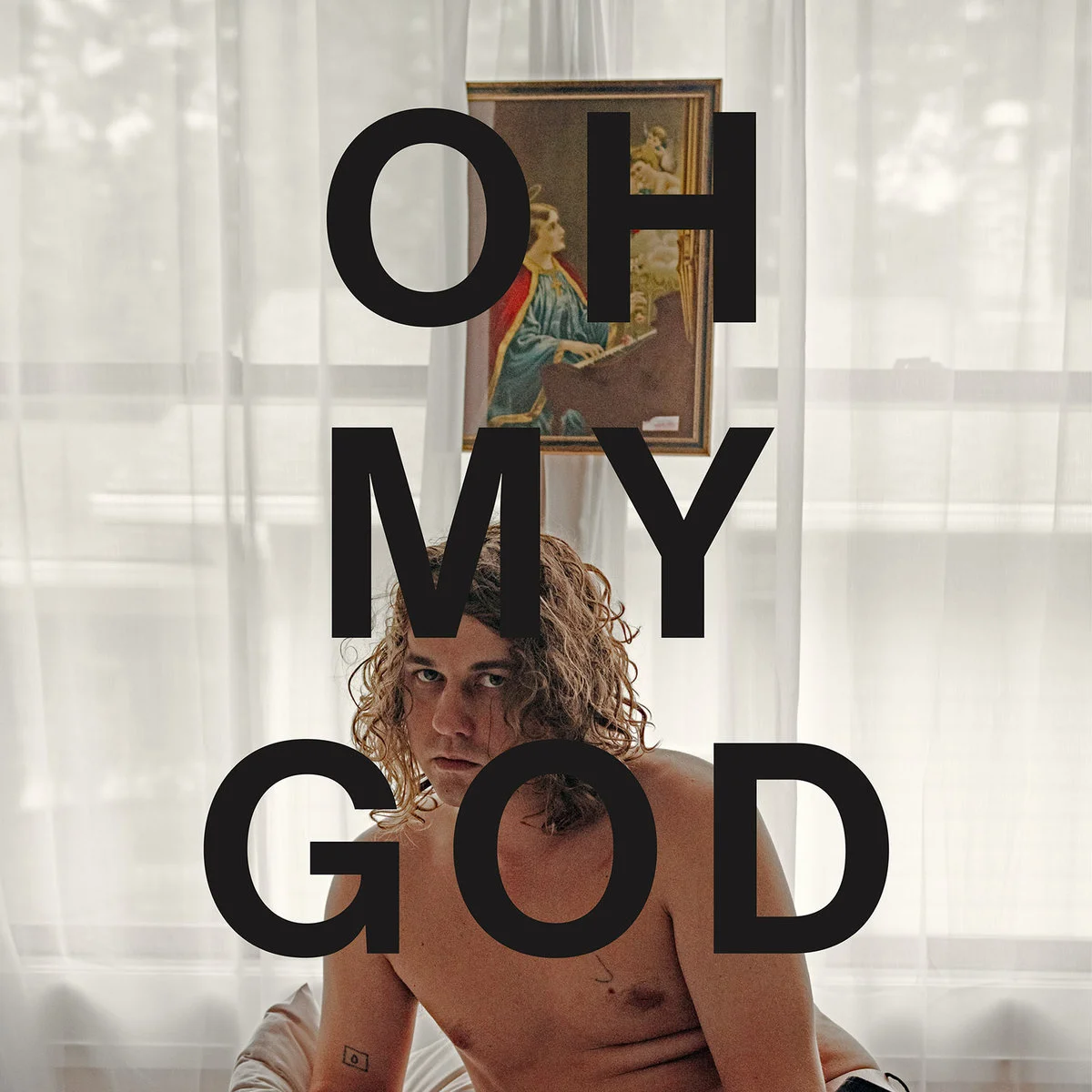

Kevin Morby’s fifth studio album, Oh My God, begins with the sound of an upright piano, past its prime—the kind you find in church backrooms, probably donated and used mostly to accompany Sunday school songs. He plays a flurry of clustered, bluesy notes up and down the keyboard before settling in on the chords, hammered out in steady quarter notes. It’s a good opening for an album, evoking a moment when sporadic musical noodling suddenly, as if through unknown inspiration, coalesces into song. I first listened to Oh My God the day my wife’s great aunt died. After the piano introduction, Morby starts singing a repetitive, “Oh my Lord, come carry me home.” It seemed appropriate. Perhaps more than coincidental.