Blog

Here he was in the form within which he could play and be, where he could flourish in the tension between past and present, now and death, grief and paradise.

Last summer, I did a Reiki session at a yoga retreat twenty miles from Lake Michigan where the woman doing the treatment said you have a real battle between your head and your heart. Afterwards, all I wanted to do was cry, walk in the woods, and stare at Lake Michigan. Reiki felt like an emotional bypass of my brain that went straight to my heart. Poetry, I think, is like that–your heart feels the impact before your brain. I probably think that because of a writer named Jonathan MacGregor.

When I came across Image’s tenth-anniversary issue in a Barnes & Noble in 1999, I’d been failing to navigate my “separate” worlds of faith and imagination in an authentic way. It’s a story I would share with a cadre of lifelong friends I’d meet at Glen Workshops throughout my forties.

What I felt was how deeply the song pierced me, even as I could remember how deeply it pierced me when I was twenty. Like any classic, the song's relevance ages with us.

Abigail Franklin has been telling me for the better part of a year that I need to listen to Preacher’s Kid by Semler. I put it on in the background a few months ago and thought, “Yeah, I like this sound.” But last week I reflected through the entirety of the EP, reading the lyrics along with it and looking up anything that didn’t make sense.

I too find myself living in an age of anxiety. Tolkien worried that the Nazis would drop a bomb on him before his work was done. I “doomscroll” my national, state, and local COVID numbers daily.

My mother loved the sound of the sea. Listening to its rhythm subdued memories that shifted in her heart and soothed pain she carried in the present. There weren’t many books on our shelves at home but there were bits of the sea: sand dollars, bleached white in the sun, starfish and coral with their neon colors and iridescent abalone, mementos from childhood vacations.

Walking out in the bold noonday light

after these million years of cold and sullen darkness,

after nightmares, this world—the thing itself—

These are strange days, the likes of which we’ve never seen. We’ve been overwhelmed by the hot takes, the long reads and think pieces…even the best ones.

I’ve spent most of my life looking for my people. Riding my bicycle through neighborhoods. Knocking on doors. Introducing myself. Being let in for a visit. The land is the only surety. And even then.

Saturday night at the 2019 Nelsonville Music Festival, Death Cab for Cutie closes their set with “Transatlanticism.” It’s the one song the guy I just started dating, who brought me here tonight, had hoped to hear.

She’s one of those women who look like she walked out of a Dorothea Lange photograph. She’s not old enough to have gone through the Great Depression, but the lines on her face suggest a story she’d never cover with makeup. She wears her grey hair in a severe braid, and her painter’s pants reflect her utilitarian disposition.

A breast. A buttock. A hip. Belly buttons and dimples. Glaciers tend to leave full bodied women in their wake. Or rather, brief encounters. Like a slip showing. A chance moment with what is ordinarily hidden. These hills, these u-shaped valleys and curved mountains, maternal mountains, strong-feminine energy mountains that, yes, can kill you if you don’t plan properly or if you’re just one of the unlucky ones no matter your wisdom and ability.

I took lessons at the YMCA pool when I was a child, like everyone else, but I did not learn to swim. I had my dog paddle reprimanded. Learned to blow bubbles by ruffling my lips, horse-like, on the water’s surface. But I’d not been taught the necessary rhythm of breath in the water—out through your nose underneath; above, a quick gasp back in.

My mother has constructed a giant dragon in her backyard. She’s carted yards of dirt in her wheelbarrow to build up the body that stretches the width of her house. With a pickaxe and shovel, she’s chopped chunks of crusty clay from her property and arranged the pieces in a scaly spine running the length of the dragon’s back.

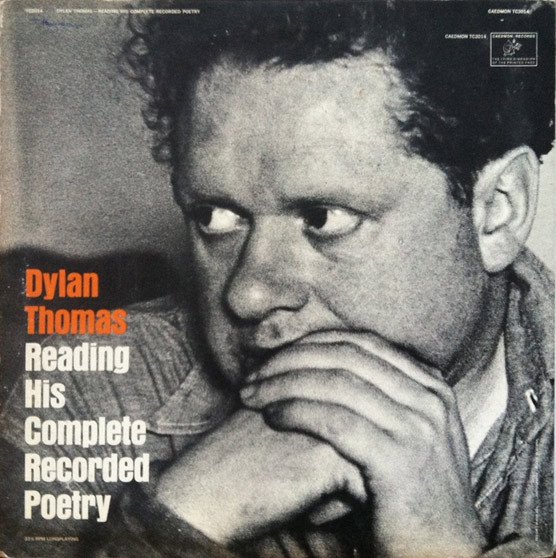

When I moved, after living for decades in one house, one of the first things I did was create a bedroom like a seaside sanctuary in shades of green and blue and sand. This is my serene thinking place, with late afternoon’s gold light streaming through the rippling, grey-green curtains. Next, I liberated my poetry books from their boxes and relocated them to alphabetical places of honor on shelves in my room and the connecting hallway. I needed their silent wisdom, their beauty, their bright light and deep shadows to surround me. They flicker alive as each day’s changing light passes over them.

Two weeks ago, I answered the phone. It’s close to 10 pm.

He is calling me up to talk politics again. ‘He’ being a family member. In our conversation where I can barely get a word in edgewise, I hear that I am a communist and a socialist and that an “illegal alien murdered Mollie Tibbetts.” I respond by telling him that her own family members didn’t want her death politicized. “Moreover, her father thanked the Latino community for their “support,” I say.

The park map had not shown the Whitetail Trail widening slightly, sprouting sparse grass to become the Bluebird, but that was my path. It cut through thick borders of leafy weed stalks and skinny-armed saplings and stocky, long trunks.

“Remember when our songs were just like prayers?” Gregory Alan Isakov asks quietly from my Pandora station. “Like gospel hymns that you called in the air?”

His guidance was gone. The number of emails we had sent each other was now fixed.