The Way of Grace: Malick's Tree of Life

Brad Fruhauff

Relief intern Jacob Slaughter can't stop thinking about this "filmmaker's film."

Relief intern Jacob Slaughter can't stop thinking about this "filmmaker's film."

“There” says the Mother to her three sons, pointing into the sky as the theme from Bedrich Smetana’s Vltava (Moldau) elegantly guides the viewer through the earliest years of a child’s life. “That’s where God lives.”

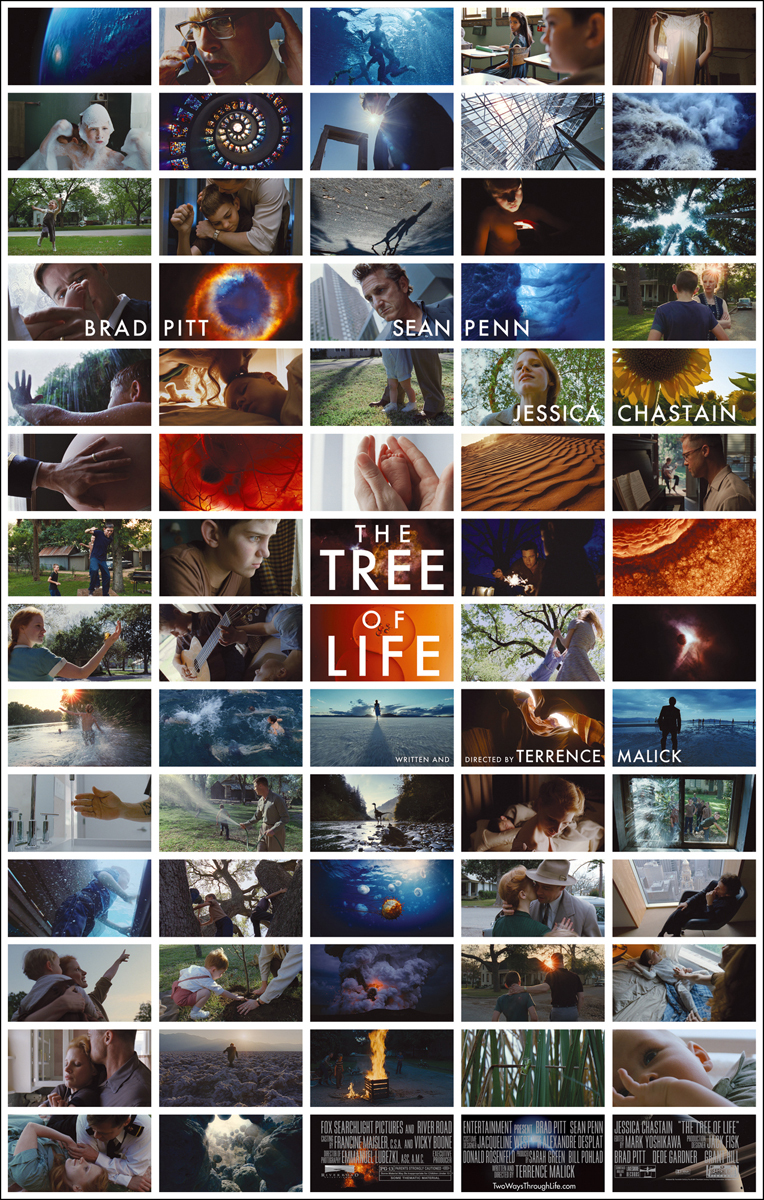

When Terence Malick’s film The Tree of Life won the Palme d'Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival last May, I was excited. Somehow the movie had worked its way into my cultural radar, and I was glad to hear positive commentary on the overall quality of the piece. To my mind Malick, like Cormac McCarthy, is one of those recluse creators who makes exactly what he wants and follows no one’s schedule but his own. Since 1973 he has directed and written only five movies, but these movies include Badlands and The Thin Red Line.

It is understandable why he is not a household name. His movies cannot be passively watched and enjoyed; they demand something which many people nowadays are unable or unwilling to give: attention. Malick’s style of filmmaking is like cinematic poetry. He is a filmmaker’s filmmaker.

Reviews of The Tree of Life exemplify this disconnect between critics and audiences perfectly. Websites that rely on content created by critics rank this film as among the best of the year. Websites that have primarily user-created content show that audience’s opinions are more polarized than I have ever seen. We’ve all said it about some piece of art before, but I think The Tree of Life is a modern example of the old cliché at work, “You either love it or hate it. Nothing in-between.”

I think it is a film better experienced than described, so I will avoid giving an intricate summary or an in-depth analysis of specific symbolism. From my own experience I can simply say that this movie has constantly been on my mind since I first saw it last summer, waiting to be watched again, once I get some time away from mountains of homework.

The movie starts with a quote from Job 38: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . . When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy.” We are introduced to a family in pain, a family experiencing the loss of one of their own. We are given insight into the mind of the Mother as she mourns the passing of a child. We hear the thoughts of the oldest son Jack as he tries to come to terms with the death of one of the people closest to him. This particular death is more than just a human tragedy, it is the cause for a religious depression. As they struggle to understand, they ask the inevitable question:

“Why? Where were You?”

The response? A twenty-minute sequence of the creation of the universe that contains some of the most awe-inspiring images in recent cinematic history.

Yet, that is not the whole response. There comes a sudden shift from the large and cosmic to the subtle and deeply personal history of the family. Through one of the better examples of montage, Malik takes us through the experiences before birth until that point of childhood in which we begin to understand the world on our own.

“There are two ways through life,” the three sons are told, “the way of nature or the way of grace.” As Jack and his two brothers grow up they have these two ways exemplified by their Father and Mother, respectively. This conflicting duality will be a part of Jack’s own journey to understanding the faith of his parents in an attempt to make it his own, and the bulk of the film functions as Jack’s bildungsroman.

The film ends with a vision of the afterlife, a moment of reconciliation between loved ones on a beach in which all that can be seen is the never-ending horizon. The scene makes sense, after all, “That’s where God lives,” as Jack was told earlier.

The last words are uttered by the Mother, “I give him to you. I give you my son.” While the meaning is explicitly an acceptance of her son’s death, I think the Biblical framework allows for one to see a secondary implication: a John 3:16 reassurance of the love of God for not only the world, but for the individual. In light of that Son, the Mother is able to trust her own into the hands of God.

As I said, I’ve just skimmed the surface of what is to be realized throughout The Tree of Life. I’ve barely mentioned any of the symbolism at play throughout the film, but hopefully you are intrigued enough to experience it for yourself. I am willing to admit that I may be inserting aspects of my own biases onto the piece, but you can’t watch The Tree of Life without engaging with the Christian faith. While Malick may not have set out to make “Christian Art,” I cannot think of a better work that portrays the tension between God’s unimaginable immensity and his love and interaction with the individual through the world He created and the people placed in one’s life.

Do yourself a favor: see this film.

Jacob Slaughter is an editorial intern with Relief. He will graduate from Trinity International University this spring with a degree in English.