Believing in Poetry in Haiti - Part 2 of 2

Adele Gallogly

(Read Part 1)

(Read Part 1)

“Create dangerously, for people who read dangerously. This is what I’ve always thought it meant to be a writer. Writing, knowing in part that no matter how trivial your words may seem, someday, somewhere, someone may risk his or her life to read them.” —Edwidge Danticat

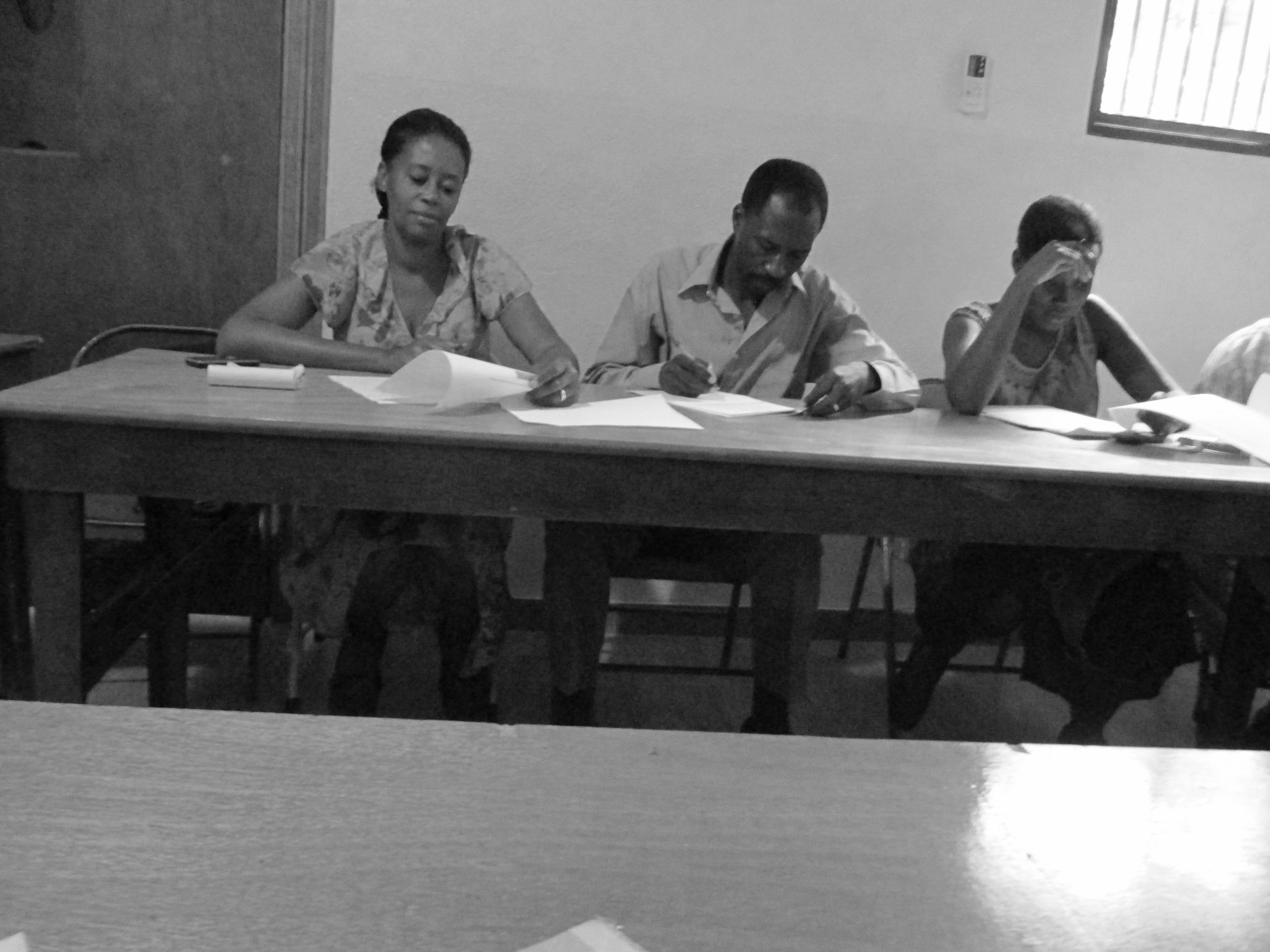

A group of Haitian men and women sit around tables in a classroom with small windows. Fans are whirring, cutting some thickness from the warm morning air. The instructor, Lunise, is teaching Chapter 4 of a literacy program in a language I do not know. She translates for me when she can, but her main focus is, as it should be, on her class. Despite the distance of my foreigner’s ear, I am grateful to be among these attentive literacy students for an hour. I make a note to try and use “we” and “our” when I write about this later.

We are learning in Creole. I have been told this is not the educational language of choice for most Haitians. Most of them would prefer to learn in French, since it is considered the language of the elite. But French would be an extra step for learners who already know word meanings and organize their thoughts in Creole. The incorporation of poetry helps make the familiar fresh. “Poetry makes Creole attractive and new for them again,” Lunise told me. I like that, a familiar language reborn through a literary form.

We learn new words to build our vocabulary, copying them out while watching the clock to time the exercise. We work through a fictional set of letters between two characters who are talking about what they have learned—how each unit of rhythm is called a "foot" of poetry and how poetry is an expression of feelings. We copy out Psalm 23 and then paraphrase it. Some students share their phrases—and while the words have necessarily shifted, the sentiments hold. “I will fear no evil, for you are with me,” for example, becomes “I won’t be afraid, you won’t leave me behind.”

The language barrier makes it difficult for me to keep up at times. The student to my left gently taps his packet of worksheets with his finger to guide me to the right page. I smile and nod in thanks as I turn to where I am supposed to be.

The Psalm 23 phrase “dark valleys” fits with the topics of a writing exercise given as homework. Students are to write three sentences analyzing the cause and effect in these topics, which Lunise translates for me. Twop moun nan prizon—overcrowding in prisons. Lapenn—sorrow or grief. Goudougoudou—a nickname for the December 2010 earthquake that is onomatopoeic, since it mimics the sounds buildings made as the ground shook.

I do not have the chance to interview these students one on one; I’m scheduled to travel out to another area to meet with students in a beginner’s class. I would love to go home with samples of poetry they have written, but they are not at that stage in their literacy journey, not yet. I have faith in the work to come, though. Poetry is taking root.

***

As I travel through the tight, packed city streets to the next literary class site, I spot a man in a baseball cap and grey t-shirt. I read the yellow text over his chest, a phrase in English: "I am not perfect, just forgive".

Or does it say just forgiven? Our car is beyond him before I can confirm. So even if I read his shirt in error, I will now remember the ending as a kind of plea or command: just forgive.

***

I am home and working on a web story about Haiti. I email Lunise to ask her about some of her favorite Haitian poets. It is still quite rare to find Haitian Creole poems translated into English, but I would love a taste of a work, however small. She sends me the poem “Testamen” (Testament) by Félix Morisseau-Leroy. It is a version that can be read online here, as posted by the Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat.

I read the poem once and immediately over again, more slowly. Then I sit awhile with the short, lively work.

A quick Google search reveals that Morisseau-Leroy was one of the first prominent writers of poetry and plays in Creole. He wrote during Papa Doc Duvalier’s autocratic regime, which was set on stopping free expression. He was nearly killed and eventually exiled. Literacy is particularly risky in tyranny.

The image of the man in the forgive t-shirt comes back to me. Forgiveness is risky, too. A forgiven person may fail us again. Reading and writing can follow this same tenuous track of comprehension found and lost.

As I remember the beginner students, Josette and Mirlaine (who I eventually wrote a story about), the phrase “nervous yet excited” comes to mind. These women fidgeted and grinned as they talked about using their new skills to find jobs that enable them to provide well for their families. Both spoke of one day reading scripture aloud in church. They are unsure yet trusting, learning lesson by lesson, and taking steps to build a healthier, more secure life.

Perhaps they, and the other Haitian students I encountered, will go on to write and even publish poetry of their own one day. Perhaps they will not. Regardless, I am heartened to know that people in their country celebrate this form's mysterious, muscular voice. Morisseau-Leroy’s poem and countless other literary works will be there for them to discover, along with the written language of the everyday.

I believe acts of forgiving have a witness which abides long after forgiveness has been given or received. Isn’t this similar to literacy, too? By writing and reading texts, we give them power and place beyond the time we know. Consider Edwidge Danticat's observations about a someday, somewhere, someone reader. There is legacy in the work of words, and these Haitian students are now a part of it.

Our literacy always outlives us. Books may puzzle us and imperfect creations may fall short of what we mean to say. Of course they do. But we are daring to read and create dangerously, anyway—making small testaments that speak to what is greater than ourselves.