Breathe Lightning

Jayne English

“Exile brings you overnight where it would normally take a lifetime to go.”

― Joseph Brodsky

“Exile brings you overnight where it would normally take a lifetime to go.”

― Joseph Brodsky

On days when the sun is shining across the oak outside my door, and colors I didn’t know it possessed bloom in the bark’s inscribed lines – gold, green, sage – I like to think about the concept of limits. The Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky, spent 18 months in a labor camp in subzero temperatures along the Arctic Circle. Some have said of this time that “Brodsky’s exile was the best year of his life...because it gave him time to read and write.” Brodsky agrees, “Even sitting there between those walls, locked up, then being moved from place to place, I was writing poems.” Brodsky’s writing flourished in confinement.

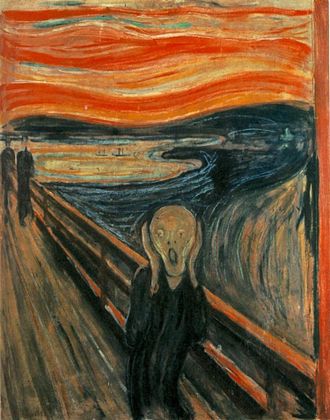

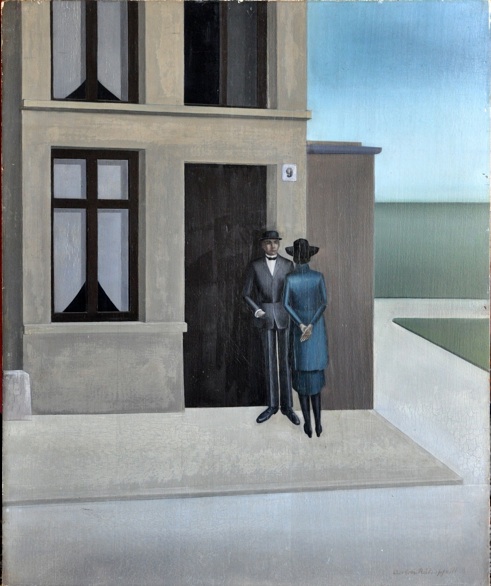

This paradox has a parallel in the art world. Post-expressionism was a revolt against Expressionism; an attempt to put the rampaging genie back in the bottle. It countered Expressionism’s fluid and mainly angst-ridden style with one placed inside limits. As Carlo Carrà suggested, it put things “in the space allotted to them.” Consider Edvard Munch’s The Scream (Expressionism) and Anton Räderscheidt’s House Nr. 9 (Post-expressionism) side by side.

The Scream seems to overflow the canvas in its intensity, while House Nr. 9 is rendered in parallels, angles, and is fixed within its borders. The painting’s strength comes from creating its essence within its limits. The overflow of emotion in The Scream plays on our senses, but so do the constraints of House Nr. 9. Its lines and muted colors present a stable backdrop for the mysterious couple. Who are they and what is their relationship to each other? Is one a door-to-door salesperson; are they lovers; is one an angel in human form? The window’s acute angles form a cross on a hill. Räderscheidt creates mood and room for imaginative interpretations within the stylistic constraints.

Don’t immovable lines seem counterproductive, and limitations seem to keep us from accomplishing our good work? Even in what might be considered an unfettered life, Emily Brontë’s prison imagery would have made the exiled Brodsky feel at home. Anne Carson’s poem, The Glass Essay, speaks about the poet and novelist:

Yet her poetry from beginning to end is concerned with prisons, vaults, cages, bars, curbs, bits, bolts, fetters, locked windows, narrow frames, aching walls.

Outwardly, Emily Brontë didn’t seem to have lines hemming her in; she was free to write and roam the moors. Whatever the constraining forces were that shaped her writing, Emily yielded to them. Carson’s poem continues from Charlotte Brontë’s perspective:

Charlotte talks firmly and calmly about…

Emily’s total subjection to a creative project she could neither understand nor control, and for which she deserves no more praise nor blame than if she had opened her mouth

“to breathe lightning.”

What is God creating in the midst of your parallel lines, your locked windows and aching walls? Do you dare? Breathe lightning.