7.1 author Jay Torrence tells some of his motivations for writing Ivywild while sharing his faith, story and creative process through an interview with one of our volunteer staff members, Alyssa Dixon.

What formal education did you receive?

For my undergraduate, I got an English degree from Wheaton College. For my MFA (Masters of Fine Art), I studied Creative writing at the University of British Columbia which is set up to dabble in different genres. I went in with a nonfiction focus and then played with nonfiction, graphic novel and play writing. I had done about ten years of professional play writing, and I wanted to play around with other creative writing genres.

How and when did you begin your career as an actor and playwright?

I actually started performing after I received my undergraduate degree. My younger brother, Ryan, and I created a sketch group in our home town, the Amish country of Ohio. Every month, we would put on a show in our church’s youth room, eventually as our crowd got larger we rented out the local high school’s auditorium.

We had a lot of fun in those years and it taught me a lot about performing and writing. I wrote the majority of what we performed and after four years of doing this, I auditioned and was casted for the Neo-Futurists. Their work was very similar to the work that I was doing with my brother.

How does your faith play into what you do as an artist?

I grew up in the church and heard these stories about flawed people and how they related to the world in very important ways. I think that these stories were meant to teach me how to think and how to respond to large issues that were beyond me as a child, adolescent and even at times as an adult. As often times, we are in the world and can not grasp these big issues. Those stories were always teaching me how to interact with the role of story telling and its relationship to real people and large concepts of wisdom and truth. That connection is in my work because it is the complexity of being human. I hope it is a small thumb print on our grasp of truth. It is not something that I am really thinking about all the time, but it is something I try to recognize and honor in my work.

How does your team work together to produce the plays you write?

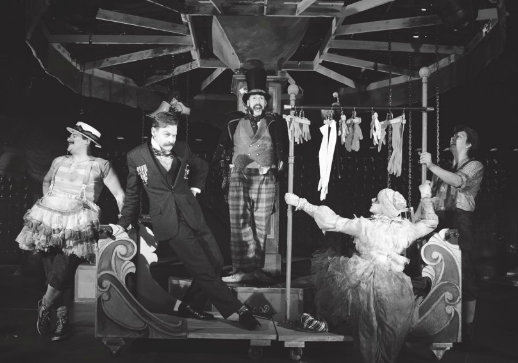

Halena Kays, the creative director of The Hypocrites theatre, of whom I worked with on Burning Bluebeard and Ivy Wild, creates a collaborative room where we come together and play with what I have written. My team really does grow the pieces I write, and I totally depend on the group as a source of inspiration, when I start writing something new. They are constantly offering ideas and voice to further what I am trying to do.

I really credit the smoothness of the collaborative process to Halena because she is really good at leading a collaborative group. We all have this goal in mind and all of our ideas are meant only to serve that goal and not ourselves at all. That creative process is a love of ours.

I have found as a playwright, getting something as far as I can creatively and then bringing it to a collaborative table allows my work to go a step further.

What I like about art is taking something from an idea and pushing it through the creative process into a final thing. I like being on that journey.

What do you love about the writing process?

For the writing process, I usually get something about history which motivates me to do the research.

The act of writing, in this process of art, is the most miserable part for me. It is the most isolated and lonely part about theatre. Sometimes when I am there, there is inspiration, but for the most part, that part of the process is pretty agonizing. It is just such an intense birthing process going from nothing to something.

I haven’t found that I am good at it and I definitely haven't found a way to avoid the misery of it. However, I have gotten good at recognizing the fact that, oh, this is familiar and I can get through it.

I wish I could say that I love sitting down and writing, but I do not. That is the part that feels like work and it is good work, a discipline. But it does not end there for me, I love hanging out and creating with the people on my team. Then getting it in front of an audience is really fun and that usually is the most rewarding and satisfying part of the process.

What was your motivation for writing Ivy Wild?

Halena Kays approached me about writing something for the The Hypocrites theatre. So we sat down and threw out a couple of ideas for new plays. When I did my research for Burning Bluebeard, I had stumbled upon the Levee District and the names “Bathhouse John” and “Hinky Dink.” I decided to come back to it when writing Ivy Wild.

I had researched about this red-light district and all the vice that was concentrated in one terrible neighborhood in Chicago. And at the helm of it was this duo Bathhouse John and Hinky DInk. The people loved John and he was this loud, brass character. He would walk down the street and people would just follow him. His partner, Hinky Dink, was the fist behind John’s life, on the sidelines taking care of business. But as a duo, historically, they set up the biggest money laundering scheme the city had ever seen.

When I stumbled on these characters, I got so excited. I get fascinated with the historical things of this world that are forgotten. I often get this romantic idea of paying tribute to people that are forgotten and I relate that to the art and the type of art that I make. Theatre happens for the people that are there, and then it disappears like a circus leaving town or like a tragic fire that consumes everything, it is very temporary. So I relate to these people who spent their lives creating art in the way that I create art, and then they are forgotten or dead. History has forgotten them.

I was fascinated about why he went to Colorado and decided to build this amusement park, it just seemed weird to me on paper. When I do research, there are always these gaps and conflicting ideas. I am just piecing it together and often take the liberty of putting myself into it and trying to answer the question “why?”. I mean, I don’t know who Bathhouse John was, other than what these people wrote and described him as. I don’t know the intentions behind his actions.

Through exploring these ideas, I became fascinated with the idea of penance, atonement and what it means to live a life of good works. I asked questions like; “Do our good works make up for our bad?” “Is that true and what does that mean?”, and “What is forgiveness?”.

I did know for sure that John went to Colorado to make an amusement park that was fun for family and kids. As I read, it felt like his life there was very distinct from his life in Chicago. I inferred that Colorado meant something to this guy, but it failed miserably.

So, I was very curious about this idea of what it means to be forgiven.

Through my research, I never knew if John’s heart was really pure, because for every gesture of goodness, there was also this flip side of gain that could be read into it. John did take a train full of dying prostitutes to Colorado Springs to get treatment. If he were a sincere person, the act of trying to help these prostitutes would be a selfless and wonderful act. However, then the Hinky Dink side of that was like “ya! get those girls better so we can make cash off of them.”

Historically, I do not know where they landed on that spectrum because its a mixture of goodness and gain. There was this tension between the two of them that I tried to create: Bathhouse John was all heart and Hinky Dink encouraged that heart because of the money it produced.

Bathhouse didn’t really think in those terms, at least in my play he didn’t. In reality, historically they could have been totally different. Their gestures of goodness are seemingly good, but what was it motivated by? Was it motivated by heart or by gain? In reality, none of that is clear historically.

My heart for my play was this: Bathhouse John returns to this abandoned park and he is given another chance to make it a place of beauty and wholesome goodness. John is hoping that it will be enough to release him from whatever void or guilt that he was in.

The first scene is just him walking around in the void, holding this consumptive amusement. That image is really specific and I wanted him to enter through nothing. He is back at the place where he got it all wrong. Now is his chance to do it all again, where he might be released from this blind empty place of guilt.

I also wanted the art of my story to celebrate fun parts of their lives and different details about the park. Some of that allows me to celebrate their lives historically and also this story of Bathhouse John trying to get it right. Ultimately, he fails again and the park burns and what he doesn't want to happen, happens. He tried to create this beautiful place that people could come and be happy at. I believe his effort was self-motivated because he wanted to make up for all the bad that he had done and in my play that was not enough.

At the end, I wrote this monologue of him owning the facts of who he is and what he did. It ends with a simple statement of him just earnestly apologizing and when he does, the park comes alive. The park in a sense accepted his apology.

Jay Torrence is author of the drama "Ivywild" in issue 7.1 of Relief.

7.1 Poet Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo writes about a broken wrist and the ritual of seeing.

7.1 Poet Elizabeth Harlan-Ferlo writes about a broken wrist and the ritual of seeing.

In the following (a reprint of the editor's note for

In the following (a reprint of the editor's note for