A Tale of Tweelie

Joy and Matthew Steem

This is neither ghost story nor a tale of suspense: it is a bit of writing about a bird teaching me insights that I should have learned a long while ago.

Read MoreUse the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

123 Street Avenue, City Town, 99999

(123) 555-6789

email@address.com

You can set your address, phone number, email and site description in the settings tab.

Link to read me page with more information.

Filtering by Category: General Curiosities

This is neither ghost story nor a tale of suspense: it is a bit of writing about a bird teaching me insights that I should have learned a long while ago.

Read More“The body interacts and changes places with apparel as we wear it, changing ruffle to ankle, in the vision of one motion. We let it affect the way we move, the way we interact, the way we shape affection, the means by which we negotiate other’s opinions of our social standing, the way we cognize our own body.”

—Daneen Wordrop,

As one who doesn’t typically pay a great deal of attention to the act of dressing, I have an ambiguous relationship with clothing. In fact, I often catch myself contemplating the necessity of clothing in negative terms, partly because over the years I have become increasingly aware of the class distinctions and identity communicating elements inherent in clothing choices. My mindset has been slowly changing though, in large part thanks to a generous benefactor of luxurious hand-me-downs.

Read MoreOne thought can produce millions of vibrations and they all go back to God ... everything does.

—John Coltrane

Do you remember playing with a gyroscope as a kid? You’d snap the string, lean down eye level with the table, and watch it spin on its axis until the momentum slowed and it wobbled to a stop. The gyroscope’s movements are the same ones that weave through our lives. It appears balanced enough, but the view from the axis can look like a lot of frantic spinning.

Read MoreWhen little, bed-bound Rusky Lionheart realizes he is going to die, he talks with his beloved older brother Jonathan, and Jonathan comforts Rusky with strange, magnificent words: “It’s only your shell that lies there, you know? You yourself fly away somewhere quite different.”

Read MoreWe are driving. My three year old daughter says cute things in the car. She says she is dreaming about brownies and milk. I want to kiss her cheeks every time she pipes up. I love her strangely and fiercely for the cute things she says at three.

Read MoreWhile writing on such a grandiose personage, it’s hard to not aspire to touch on a great many magnificent things. And what numerous numbers there are! Ashamedly, I have not read much Coleridge before. I knew of him historically speaking, and what he was known for and with whom he hob-knobbed, but I had read little past “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and a few others. Then I landed his Aids to Reflection.

Read MoreI am not here for my own inner peace.

No, I am at this for the inner pockets of my wallet. My boss walks into the office, which is separated from the studio by an opening in the wall and turns off the light, leaving me to sit alone in the darkness.

Read MoreI am not the first, nor will I be the last to quake and quiver at the rather odd, inexplicable mixture of symptoms to which artists will point for their embryonic work—that most baffling conundrum otherwise known as “the creative process.” It is a rather stupefying concoction of mysteries perhaps best left to psychologists, philosophers, and theologians. When it arrives at one’s door, it does so unbidden and with an inconvenient sense of either timing or manners.

Read More

The best reason for a revival of philosophy is that unless a man has a philosophy certain horrible things will happen to him. He will be practical; he will be progressive; he will cultivate efficiency. — G.K. Chesterton

Any reader of Chesterton knows that he is quite quotable; however, sometimes his quotidian nature can also stump and confound. Take the above for instance: while we can appreciate the need for good philosophy [think C.S. Lewis] what are we to do with the “horrible things” that Chesterton stands against? After all, in our culture isn’t practicality a good thing? And that goes for being progressive and efficient too, not?

We want practical money managers; progressive medical technology; and surely, efficient cars and refrigerators.

But it is not these things that Chesterton warns about.

G.K’s primary concern is that these traits become ends in and of themselves without reflection on their potential consequences. Take for instance his gripe about “a practical man.” For Chesterton, the practical man cares only about the final results of an endeavour (whether that be in business or politics or whatever) and not what took place in the interim (the steps which were taken to achieve the end result: an example would be the food industry using GMO food without considering the potential consequence). Chesterton posits, “When will people see the simple fact that practicality is a question of means, not of ends?”

For Chesterton, being practical is linked to being progressive. So back to the example of GMO: a perfect example of progress. Progressives look ahead to solve current problems without doing the hard work of fixing something now. A good example might be the average power consumer being unwilling to lower their power outage by 15%, instead trusting that the power companies will, with scientific aid, be able to simply reduce the amount of pollution that is created. Or, the desire to increase crop production through GMO – instead of tackling the uglier and slightly more work intensive trouble of consumer waste (stats proclaim that we waste between 30-40% of our food). Chesterton doesn’t approve of putting one’s trust in the future when we could take action now.

Lastly, efficiency itself is value neutral; as a tool it can be employed for either good or bad. Further, once turned into a process, it can be easily used for control. Most of us know that the Nazi death camps were pristinely efficient. It was this very efficiency which palpably made the death camps so heinous. Euthanasia is efficient as were the desired outcomes of eugenic programs. Less nasty examples were the assembly line productions which turned workers into automatons. Efficiency is a means, but it is not an end in itself. It’s a handy tool that can make our lives better, but it must be placed in its proper hierarchy—i.e. below us. Ultimately, Chesterton wants us to ascertain, whenever efficiency is employed, what is the end game? And whom does it ultimately serve?

We’re driving home from shopping, two 40-something parents and their three teen and tweens. It’s January. Call us old-fashioned—we listen to the radio, Rick Dees. It’s not just the Weekly Top Forty; it’s a countdown of #1s. A list of a list. We click around but the kids insist—“Go back to Rick Dees!”This pop culture is ruining them, I think, ruining us all, a proud tradition of pop culture ruin for every generation—Rick Dees, Casey Kasem, Dick Clark.

Read MoreHere's a game for wordophiles where earth, breath and sheet are three words you can spell with the letters in the word heartbeats. Setter, rate, and bra are three more. Steep, if your rules let the “b” swing around. Strafe if you let one “t” grow a canopy. Tree is there. There, too. And three. And others spring from the page if you string multiples:

Read MoreIn MacDonald’s classic story, the chronically neglected child, Phosy Greatorex, sits alone in church while the vicar preaches that God manifests his love by correcting human souls. Whom the Lord loveth, he chasteneth, he quotes from the heart of Scripture. In her lonely desperation, Phosy pines for this chastisement, if that be the proof of love—any love. When the bitter pallor of an unfathomable loss visits the child on Christmas morning, her innocent acceptance of love’s visitation is so complete that she does not recoil, but gazes full-faced into the heart of her grief, embracing what she must.

Read MoreI owe you an apology. I've overstayed my sabbatical. The one I never cleared with the Editor. The one, which by definition comes “every seven years”, I took five years early. And now I can only fall on my sword, which is my pen, which of course is this keyboard. Mea culpa. I very much desire reunion with you, Dear Reader, in its pain and joy. Yes, pain, salved in confession and return to labors, and joy that is regular mindfulness of you. So by the gravity of guilt and the hope of renewal, I sit to write.

Read More I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story, “Gimpel the Fool.” The story was in a literature textbook I was using, and I didn’t have anyone to tell me what it meant. That was all the better. Even though I count it as a real flaw in my literary education that no one brought up the archetype of the holy fool, a story like Singer’s is best stumbled on alone, where the story’s very oddity throws you into vertigo.

I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story, “Gimpel the Fool.” The story was in a literature textbook I was using, and I didn’t have anyone to tell me what it meant. That was all the better. Even though I count it as a real flaw in my literary education that no one brought up the archetype of the holy fool, a story like Singer’s is best stumbled on alone, where the story’s very oddity throws you into vertigo.

In the story, Gimpel the baker is the butt of everyone’s jokes. The biggest joke? The townspeople marry him off Hosea-like to the town prostitute, who bears him six illegitimate children. Repeatedly, Gimpel takes action to end the marriage, but instead comes to conclusions like, “What’s the good of not believing? Today it’s your wife you don’t believe; tomorrow it’s God himself you won’t take stock in.”

For a long time, I’ve struggled with the designation of Christians as “believers” for two reasons: on the one hand because it’s too wide, designating naivety and gullibility for products from Buddy Christ bobbleheads to the Precious Moments Chapel; on the other hand, because it’s too narrow, as Christians seem to be willing to believe in primarily one direction, primarily allegorical—as in, Gandalf is Jesus and the dwarves are the twelve disciples (Crap, there’s thirteen; well, Tolkien’s a word guy, must’ve miscounted).

Then, in graduate school, I came upon, well, unbelievers.

One of them, in 19th Century Nature Writing, called into question the basic ethic of the course, that we should value life because life was itself a good. “How do I know that ‘life’ is a ‘good’?” she asked. “How do I know that it’s not better that life go extinct?”

Now that’s radical, respectable doubt. She’s right: “We should value life because we should value life” is not believing; it’s tail-chasing.

In another class, I read Life of Pi with a smattering of students who were studying to be experts of story. Famously, that book spends two-hundred-plus pages recounting the trans-pacific trip of a boy on a lifeboat with a hyena, an orangutan, and a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. Then, it performs a bait-and-switch. Investigators arrive on the scene who doubt the story. The survivor, Pi, then tells them a different story than the one we’ve been reading, a naturalistic tale in which all the characters are humans who kill each other in order to survive. The dilemma is, which story do you believe?

I take pride in the fact that I was the only one who took the first story. After all, I’m a believer. The rest? Unbelievers.

As per Singer’s story, “believing” is dangerous business: other people might quite literally shit on you, continually heap insults on you, stick you with their illegitimate children. But if you clump together with other believers under one roof and call it a church, what better place for illegitimate children?

I remember one critic on Singer’s story suggested that the Gimpels of the world get cooked in Nazi ovens. But isn’t that exactly the problem—that we blame the victim, believers, at the expense of the cynics? “Don’t believe,” the lesson goes, “or the Nazi’s will get you—we’re helpless to prevent them from rising to power and killing millions.”

Here’s the dirty little secret of a rationalist society: we revile the believer who sends all his money to the TV evangelists more than the TV evangelist; we revile Trump or Hillary supporters more than Trump or Hillary him- or herself.

I wonder if radical believing could blow up our polarized society. What happens if you believe what you see on Fox and CNN? What happens if you believe climate change and believe its doubters? What would happen if we believed everything that was said by both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton—and the green party—and the legalize marijuana party?

Maybe the holy fool explains the election season in America. Maybe that’s the only way to explain it. We turn into believers every four years.

But only partial believers. We should throw open the floodgates of belief, believe in every and all directions.

The Holy Fool archetype has roots in scripture—in Isaiah, Hosea, Ezekiel, who actually refused God’s command to cook his food over burning human dung and settled for animal scat instead.

Why not give all away all your money, marry a prostitute, support her children with your diligent work at the bakery or prophesying at the town gate?

One final sign that I’m right on this, that I’m going to become an omnivorous believer: as I wrote this—no lie—I received a “random” email form a listserv I’m a part of.

It was from Richard Parker.

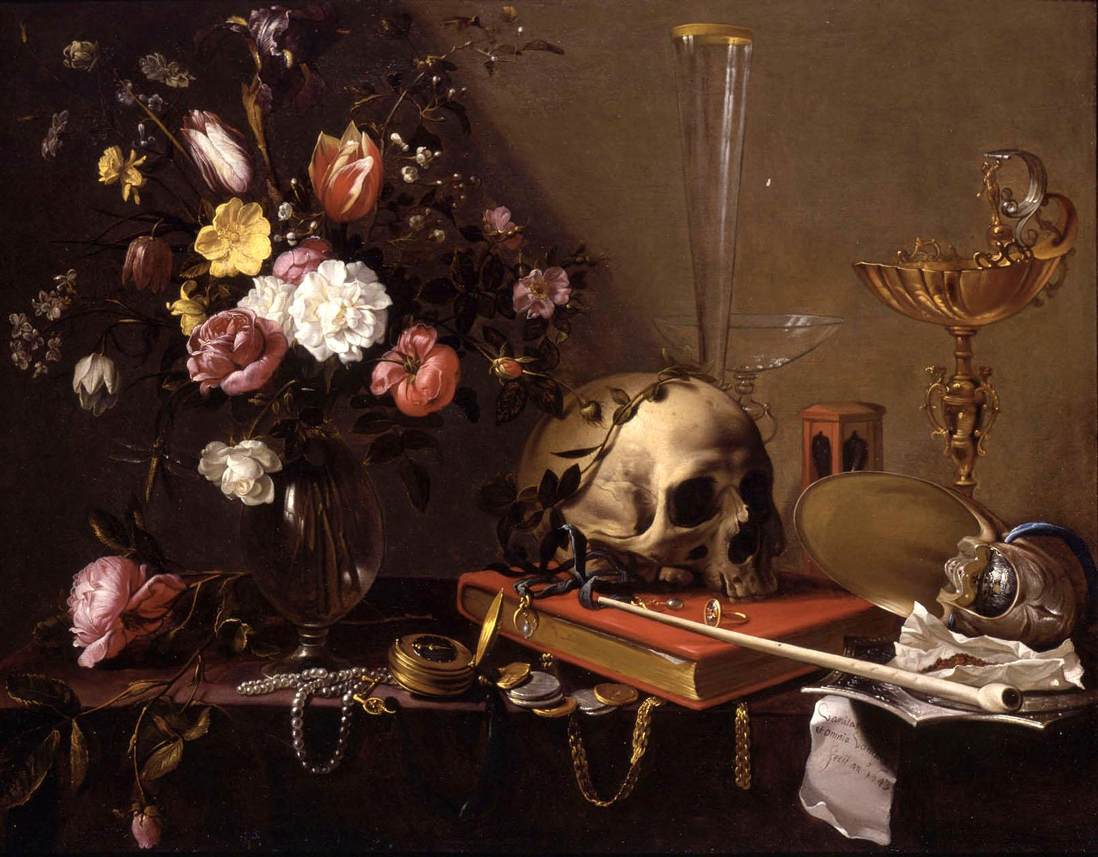

The truth is that man’s horror of the skeleton is not horror of death at all. It is man’s eccentric glory that he has not, generally speaking, any objection to being dead, but has a very serious objection to being undignified. And the fundamental matter which troubles him in the skeleton is the reminder that the ground-plan of his appearance is shamelessly grotesque. - G.K. Chesterton, "A Defense of Skeletons"

In his quirky essay, Chesterton writes of walking through woods where the forest folk kept apologizing that it was winter and the trees were bereft of foliage. “There was evidently a general feeling that I had caught the trees in a kind of disgraceful dishabille and that they ought not to be seen until, like the first human sinners, they had covered themselves with leaves.” We’re a lot like those peasants regarding our own souls, trying to appear more clothed and commendable than we are, knocking around with planks sticking out of our eye sockets while we swipe at someone else’s dislodged eyelash with a bony phalange and hope no one mistakes us for a character in Saint-Saëns tone poem, Danse Macabre. (See St. Matthew 7:3) Yet deep down we know that when death strips us of the pretty outer wrappings, our “shamelessly grotesque” frame will be exposed by the likes of devouring worms.

How little of grace we understand. For if our hearts were more gripped by grace, we might not only be less shy about our undignified skeletons, but waste less energy in denial about the inevitable core of our human nature. Who knows, laughing at our souls’ bare bones might be just the thing that begins to heal our poorly disguised pride.

As an example, I give you my recent preparation for the Sacrament of Confession. I wrote out my tiresome, amateurish sins on a 3x5 card as usual, using a pencil (badly in need of sharpening) so that I could tweak my wording. Somewhere down the list I wrote, “I’ve been jealous of another’s life.” What nonsense. It isn’t the other’s life I’m jealous of; I have one of my own. And who is this ambiguous “another?” I forced myself to erase and rewrite the embarrassing truth: “I’ve been chronically jealous of a close friend’s wealth and opportunities.” How petty the words looked on paper, how undignified. Still, I felt a twinge of elation in my brute honesty, blurted out the next day at church before the icon of Christ while the priest stood by. For in my insistence on specifics I had momentarily conquered that eccentric glory Chesterton talks about, that tendency to grope for coverings to hide the truth of what I am. And I take heart that someday I might be comfortable enough with my skeleton that I can boldly dash off concise sins of omission and commission with an expensive pen that doesn’t skip ink, and without hesitation. “Let our sins be strong,” Martin Luther said. And let our willingness to admit them for what they actually are be stronger still.

Afterward, I turned from the icon and went my way, vaguely amused. I forgot to look into its glossy surface to see whether a reflection of my own skull was grinning back at me.

“My heart is not proud, Lord, my eyes are not haughty; I do not concern myself with great matters or things too wonderful for me. But I have calmed and quieted myself, I am like a weaned child with its mother; like a weaned child I am content.” —Psalm 131:1-2

When I was 16 I spent three weeks on a Christian canoe trip in the northernmost part of Minnesota. Battling constant mosquitos (the other state bird, goes the joke), hoisting a 70 pound Alumacraft canoe on my sunburnt shoulders, and not showering for over 20 days were among the many challenges; discovering the tiniest blueberries along the rocky shore, hearing mournful loon cries, and journaling each morning were among the many joys. Looking back now, my age now doubled, I marvel at the sheer time I spent away from modern life and its responsibilities.

Being a Christian wilderness trip, our instructors made sure we had a daily dose of Jesus along with our morning oatmeal. They chose Psalm 131 as our theme scripture, which we read together many times by the smoky campfire. “I have calmed and quieted myself,” was an easy verse for me to ponder as I sat at the water’s edge, watching the morning sun burn off mist on the lake. The next part: “I am like a weaned child with its mother; like a weaned child I am content,” was more confusing. I was a teenager who didn’t know any nursing mothers; I had no younger siblings or cousins to observe. What was a weaned child like? How is God like a mother, one who no longer offers her breast?

This verse resurfaced for me recently when I was nursing my one-year old to sleep for his afternoon nap, his fingers reaching up to gently stroke my cheek. I could have stopped nursing him ages ago —he doesn’t need breastmilk to have a healthy diet—but I enjoy the time of connecting with my baby who is becoming more independent with each passing day. My son enjoys it too; he loudly cries for “milkies time!” when he needs extra comfort. Together we snuggle up, staring into each other’s eyes, and I marvel at how my body continues to provide food for this baby it grew and birthed.

Even so, the time is coming when our nursing times will dwindle. Weaning is inevitable. And, while I will mourn the end of this special connection, I will also feel relief. Breastfeeding can be painful, exhausting, annoying. Weaning my son will mean more personal freedom; it will mean I can leave him for several days if needed. It will mean I can wish him good morning without yanking up my shirt.

I wonder at how God as described in Psalm 131 must feel, her weaned child at her side. Does she feel relief that her baby no longer claws at her breast, demanding the most basic of nourishment? Does she grieve at how her baby is now a child, strong enough to eat solid food without any supplementation?

My guess is that God feels peace knowing her child has a strong enough attachment to contently sit by her side, no longer needing breastmilk. Her child sits quietly, trusting that the world is—on the whole—a safe place and that he or she is deeply loved. Infancy is over; the child only needs her mother’s presence.

When I was 16 and paddling into strong winds on windy lakes, I prayed for God’s strength and could literally feel new energy entering my muscles, powering my strokes. I was “on fire” for Jesus; God’s love was as real to me as the canoe paddle in my hand. These days, I cycle through doubt and cynicism, only to find myself crying during hymns in church. I am not a contented child, calm and quiet in the company of her mother. I yearn to understand all that I cannot understand.

I not the model child, but I know God is still here, sitting nearby. I imagine she is watching me fondly, offering her peace if only I will still my mind.

“Every day is a gift. It's just, does it have to be a pair of socks?” —Anthony Soprano

After nearly dying from a gunshot wound inflicted by his uncle, Tony Soprano discovered a new vibrancy to life. He was deeply moved by his wife, Carmela’s, watchfulness and care through his ordeal, and was overjoyed to have more time to spend with his daughter and son. But as his strength and health returned, Tony morosely quipped the line about socks when explaining to his therapist, Dr. Melfi, how his pursuit of other women was being strangled by his newfound gratefulness for Carmela.

In the first season of The Sopranos, I had hope for this complicated character. Tony was a murderous, blackhearted thug but he was also warmhearted and generous. I could not tell if his love for family would conquer his love for so many other things. But I thought something promising might be stirring when he became captivated by paintings. He assumed the one outside Melfi’s office was a “psychological picture” to trick him. Melfi asks, “What does that picture say to you?” Tony responds, “It says, ‘Hey asshole, we’re from Harvard, and what do you think of this spooky, drepressin’ barn and this rotted out tree we put here?’” Melfi helps Tony see that the painting is reflecting his turmoil over losing his good friend and mob boss, Jackie Aprile, to cancer. We know this by the way Tony shouts his favorite expletive at Melfi and slams her door as he leaves. Another painting that mystified Tony was in his cumare’s apartment. “What’s that paintin’ mean to you?” he asked Irina, scrutinizing it as he dressed. “Nothing,” she says through her Russian accent. “It just reminds me of David Hockey [sic].”

I think if Tony had pursued these shadows of that indefinable something that speaks to us—sometimes shakes us—from paintings and poems and literature, maybe he could have extracted himself from the gangster quagmire. Maybe that’s biting off more sfogliatella than we can chew.

But isn’t it true that art, in all its forms, is sometimes how God, the one who speaks through images and metaphor, draws our attention to him? Isn’t this a bounty that we, blackhearted as we are, really have no claim to? Why is there art in the first place? Why has it been saved throughout history? So much of the art we love would have been lost if not for the sometimes quixotic, sometimes manic rescue by those who felt called to preserve it. Van Gogh’s paintings rose to prominence after his death because his sister-in-law, Johanna Bonger, carefully sold and curated them; more than a thousand works of art that could have been destroyed in WWII were saved because Cornelius Gurlitt hid them and hermited himself with them in his Munich apartment for fifty years; Emily Dickinson’s family saved for us the 1,800 poems found in her room in tidy bundles after her death. Isn’t art a hint of God’s rescue? Just one example of the gracious unfairness he extends to us to point us to what lies beyond us, and within us?

I love how the ending of The Sopranos is left to our imaginations. I like to think that Tony began to accompany Carmella on her trips to museums, and engaged A.J. in the existential questions that were chasing him. I like to think his pursuit of questions and art woke him to this new sense of unfairness. Maybe it would have made a difference. Maybe he would have found that life’s gifts are far grander than socks.

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever Tottenham plays I wear a particular shirt. When I take foul shouts I spin the ball, bounce three times, spin the ball and shoot. Once, during a playoff game between the Red Sox and Cleveland in college, I refused to exit the dorm during a fire drill because I didn’t want to disturb the thin fabric between me and the late-inning rally occurring a thousand miles away. (Also: the guy who organized the fire drill and physically removed me was from Cleveland, so…) Because it seems to alway work, this entrenches the superstition.I do this with writing, too. Limiting the number of drafts, pre-determined writing times, who and who doesn’t read it before I feel it’s complete, writing in the study vs writing in the kitchen, surrounded by books or surrounded by the kids.

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever Tottenham plays I wear a particular shirt. When I take foul shouts I spin the ball, bounce three times, spin the ball and shoot. Once, during a playoff game between the Red Sox and Cleveland in college, I refused to exit the dorm during a fire drill because I didn’t want to disturb the thin fabric between me and the late-inning rally occurring a thousand miles away. (Also: the guy who organized the fire drill and physically removed me was from Cleveland, so…) Because it seems to alway work, this entrenches the superstition.I do this with writing, too. Limiting the number of drafts, pre-determined writing times, who and who doesn’t read it before I feel it’s complete, writing in the study vs writing in the kitchen, surrounded by books or surrounded by the kids.

But perhaps these replications aren’t superstition. Maybe it’s more scientific. Because whenever an experiment is produced, one that yields results, science demands that same experiment be exactly replicated. As Alan Lightman says, “the results must be reproduced… in order to gain acceptance.”

The deeply humorous Jorge Luis Borges examined this same tendency in the fantastic short story-disguised-as-an-imaginary book review, Pierre Menard, Author the Quixote. Menard wants to write Don Quixote. However, he does not want to compose another Don Quixote, or even an anachronistic 20th century version of Don Quixote. Menard wants to compose “the Don Quixote.” He wants to match it word for word, sentence for sentence, idea for idea. Don Quixote being an “accidental book”, Menard’s endeavor to recreate it will make it better.

He believes there is a way to accomplish this: “to know Spanish well, to re-embrace the Catholic faith, to fight against the Moors and Turks, to forget European history between 1602 and 1918 [the year this story takes place], and to be Miguel de Cervantes. Menard dismisses this method it for it’s obviousness (and impossibility!). Instead, he suggests it is infinitely more profound to be a 20th century author and arrive at Don Quixote. Borges reveals that Menard does accomplish this task and though the texts, he says, are identical, Menard’s is infinitely richer.

But literature (and all Art) isn’t like science. It absolutely balks at the need to be reproduced to find acceptance. That’s one of the ironies Borges is getting at, I think.

Because we homeschool, it’s our task to teach science. Whenever I recreate a science experiment for the kids, there is a certain awe that permeates. Because here I am, recreating this truth that helped change the world — whether it’s understanding the rotation of the earth or why things float or what happens to water at different stages of matter. I’ve found that these simple truths of science, so widely accepted, resonate even more strongly because I’ve made them occur myself.

Would it be better if writing worked liked this? What if you or I could compose a great work of literature verbatim? Would our exactly replicated version of Don Quixote or Pride and Prejudice or Things Fall Apart be better? Would this diminish the work itself because it ceases then to be unique, or would this cement the truth of the work more firmly?

![By Thesupermat (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12239656ca13c4525ec5/1487540771195/Pilate-Gesture.jpg?format=original) It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

I don't think I understood what gesture was before Paula Huston introduced it to me three years ago. Gestures come in all styles and types, from dramatic to mundane, even compulsive. Just yesterday, in the middle of a class that I team teach, as the other prof did his thing, I found myself pulling at the point of my lip, a bad habit from childhood that my wife has been trying to break me of for years. It’s the kind of thing I used to be self-conscious of, the unguarded moments when we return to childhood coping mechanisms.

It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

I don't think I understood what gesture was before Paula Huston introduced it to me three years ago. Gestures come in all styles and types, from dramatic to mundane, even compulsive. Just yesterday, in the middle of a class that I team teach, as the other prof did his thing, I found myself pulling at the point of my lip, a bad habit from childhood that my wife has been trying to break me of for years. It’s the kind of thing I used to be self-conscious of, the unguarded moments when we return to childhood coping mechanisms.

Then I learned about gesture.

In Bich Minh Nguyen’s book Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, a memoir about growing up Vietnamese and Buddhist in white, Christian Grand Rapids, Nguyen creates a character named Jennifer Vander Wal, a girl who seems straight out of a Cheer commercial due to the clean, controlled, middle class figure she cuts in life. Except for one thing: Jennifer compulsively licks her top lip, a glimpse, says Nguyen, of her lack of control, her humanity, and as such a hopeful gesture in its own mundane way.

So, standing in front of a class of college seniors, in that weird position of vulnerable power that is teaching, I kept pulling my lip, marking my humanity.

I love good gestures in writing, am constantly on the lookout for them. And I want to write good gestures, for which there is at least one clear truth: You can't force them. If they are to carry power, they should be either liturgical, coming from a pattern of gesture that lends them some weight, or they must spring from someplace so surprising that they flip the script. That's why every year students miss one of the simplest, most profound gesture in literature, that of the grandmother from Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”: “She reached out and touched him on the shoulder.” Simple, meaningful touch, reaching across the barriers that the grandmother herself has been attempting to put between her and the Misfit, and for which she receives a more violent return gesture, which is all students see.

The power of gesture is why Matthew doesn’t fail to give us the political stunt of Pontius Pilate. The staging, the liturgical water, a handwashing that washed nothing, an unbaptism. Or why several gospel writers give us our savior’s much more meaningful washing gesture, one that came out of a liturgy the disciples recognized as something performed by a servant: the stripped-down Son of God wrapped in a towel, bowing before them, the lowly-intimate touch of cleaning their dirty feet, a gesture that washed everything.

Yesterday, in Intro to Lit we looked at Kim Addonizio’s "First Poem for You." Students are mystified by the poem’s touches, how the speaker traces her lover’s tattoos, contemplating that they’ll last even beyond their love, till he’s “seared to ashes.” “Such permanence is terrifying,” the speaker says, “So I touch them in the dark; but touch them, trying.”

This is a pretty good prayer for our times. All of postmodern life feels like a handwashing. Black lives matter. Tribal battles for rights. Sex trafficking. Prison reform. International labor abuses. Environmental destruction. All broad headings about which we try to say, “It’s not my fault, it doesn’t concern me,” but behind which are specific lives, specific plots of land, local ecosystems.

Perhaps the answer is gesture. To move beyond the headline, to make contact with someone, to reach out a hand, to “touch them, trying.”

Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting

I do not know which to prefer, The beauty of inflections Or the beauty of innuendoes, The blackbird whistling Or just after.

— Wallace Stevens

I hear it first thing in the morning. Though it's not really silence. There's the whir of the fan, the slowly ticking clock. It's not so much the absence of sound that defines silence, but a moment when the second hand slows the spinning Earth and creates an expansiveness of time. Not just on the borderlands of waking and sleeping, we cross the threshold into this broad space more often than we realize. Usually artists take us there.

John Cage ushered us into this expansiveness in a concert hall. With a musician sitting quietly at the piano, we heard for 4’33” sounds that dwelled in the absence of the music; sounds the shifting audience made, sounds the building made as it breathed. Cage believed silence couldn’t be achieved because there are always sounds, even as he discovered two sounds in an anechoic chamber. In his book Silence: Lectures and Writings, he writes: “When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation.” Cage was influenced by . Which was simply that, canvases Rauschenberg had painted white (see image above). To Cage they were “not empty but supercharged with a kind of sacred joy.” Cage referred to the paintings as “airports for lights, shadows, and particles.” Silence, like an empty canvas, is a populated world.

Maybe silence was the world that opened to artist John Muth as he speaks about finding in brushstrokes “a quality to the line,” in the work of Japanese painters and calligraphers, that captured his attention as a young child. A quality that he carries into his own work. When he draws with children, he shows them that the “essential nature” of a subject “can be found very quickly in the movements of the lines.”

In her poem “Elm Street,” Suzanne Cleary leads us into this world of slow motion, of silence, by telling us the story of a man sitting on the porch with his guitar, not playing, but getting ready to play. The whole street is in a state of suspended animation before the first strings are strummed. She uses words like listen, pause, lost his place, the line halted, to help us step into the realm of silence. This is where the truck driver rolls down his window, not to call out to his neighbor, or shoo a dog out of the road. He rolls down the window to “stick an elbow out.” She tells us about the Matisse forger who could copy his paintings, “I mastered his line, it was his pause I could not master.” The whole poem is full of these heartbeats, like the music hall with a silent pianist. The poem doesn’t resolve with the man playing his guitar, it leaves us in this momentous expanse of time before he begins.

Clarinetist, Martin Frost describes entering this world when he speaks about his instrument. “‘What makes it special is the moment when silence suddenly starts to vibrate,’ he said. ‘Somewhere in that shadow land between silence and sound is the soul of the clarinet.’” He says “soul of the clarinet,” but you could easily fill in the blank with— the soul of the blackbird, the soul of the line of calligraphy, the soul of the neighborhood pulsing before the guitar strings are strummed.

What’s in the silence? Artists open its door for us, John Cage says, as “simply a way of waking up to the very life we're living.”