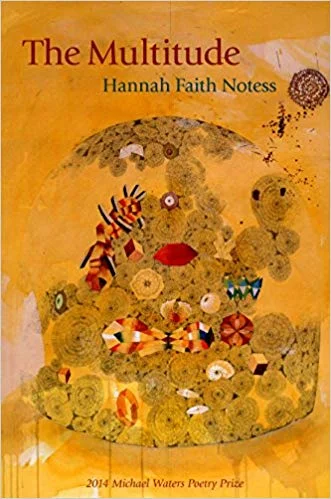

The Multitude, Hannah Faith Notess

Megan Pooler

Every once in a while, a writer beautifully expresses the human longing for illumination, causing the reader to sit still for a moment, unable to jump right up and re-enter the everyday world. Hannah Faith Notess offers this experience in her collection of poems, The Multitude. Elements of fantasy run throughout the collection, but the poems remain grounded in the crusty details of daily life. Their array of images builds layers of meaning and connection which become fleeting with any attempt to firmly explain them. With a quiet mix of doubt and certainty, Notess’ poems share the desire to define the unknown with the reader.

Notess opens the collection with “Endor (Disambiguation),” where “a creature carefully draws a map / of things connected to other things” (lines 3-4). There are many aspects, like this Star Wars reference, that bring nerdish joy to reading Notess’ poems. This poem returns to the speaker’s childhood when “There were so many worlds / I longed to visit” and be welcomed (26-27). She dreams of a place where disambiguation happens. The hunt for clarity carries through many of the poems in The Multitude.

That desire becomes the soul’s search in “St. Augustine Enters the World’s Largest Pac-Man Maze.” The speaker says, “Through rooms and corridors / … / I seek you, my Creator” but, she is unable to find him as she attempts to understand the nature of the soul (5, 8). The poem ends with determination, but no answers: “Oh, I will search / every corner of each city. / … / yet / will I hunger” (24-25, 28-29). This nod to Pac-Man, who is always eating, shows Notess’ gentle humor and use of video games, as well as other elements of fantasy, to depict the need to pin down what faith means.

The Pac-Man maze seems inescapable, but, video games always start over. Notess uses this fact to describe the necessity of facing our past. Many poems in The Multitude have ghosts and memories the speaker revisits in her quest to understand the unknown and, perhaps, find faith. While there is a sense of being haunted by these ghosts—“You are not alone / … / the dead wait patiently at the back of your neck”—returning to the past is part of the quest for meaning (“The Multitude,” lines 1, 3). In “Mario World,” the speaker realizes that “Ghosts find us every day, / but we’ll go back to gather what we need” (10, 13-14). Time folds over on itself, bringing past and present together in the continual chance to begin again and carry on. This is often presented as a terrifying proposition, but, for Notess, it is full of hope and potential. One of my personal favorites, “Yoshi (A Pastoral),” uses video game imagery to create a vision of paradise where “even the deserts will bloom / with brilliant sand blossoms” (15, 16). The poem’s speaker says, “Meet me in arcadia / the forest where I was born/ … / I will be reborn / and reborn and reborn” (1-2, 27-28). Without any punctuation, this poem flows through its lines seamlessly, never ending, always being reborn.

The exploration is continual because as soon as we think we’ve perfectly mapped connections, their meanings slip out of our grasp. Understanding is elusive. The collection’s title poem, “The Multitude,” comes last. It ends with silence, “the kind / that makes you wonder what you were meant to hear” (29-30). Notess’ poems give the reader a momentary experience of clarity before it shifts and becomes something new, quietly undoing the work we put into clearly defining their essence. She tells us we can try but may never find the definitions we’re looking for. Instead, this collection encourages us to “Think of all the farthest places you never reached / … / Parts of you are still there waiting for you” (“Ghost House Level,” 1, 17). The beauty of these poems, and the search they describe, is deeply satisfying yet leaves you hungry for more.

Megan Pooler is the Book Review Editor for Relief journal and is grateful to be part of a community celebrating the intersection of art and faith. A creative nonfiction writer and graduate of Whitworth University, she lives in Bend, OR where she works as a digital content curator for a travel company. When not agonizing over the right word choice for her essays, she can be found cooking with her family and friends, playing on the water, or curled up with her dog and a classic movie.