Our Turn to Remember Ray Bradbury

Brad Fruhauff

Ray Bradbury died on June 5 after a lengthy illness. We at Relief try not to be foolishly nostalgic, so we are not "devastated" by this news, as some people put it: the man lived a vibrant, active life and had few regrets. The best way to mark his death is to pay our respects to his gift to us. Following are reflections from three of us at Relief and The Midnight Diner.

Ray Bradbury died on June 5 after a lengthy illness. We at Relief try not to be foolishly nostalgic, so we are not "devastated" by this news, as some people put it: the man lived a vibrant, active life and had few regrets. The best way to mark his death is to pay our respects to his gift to us. Following are reflections from three of us at Relief and The Midnight Diner.

Brad Fruhauff, Editor-in-Chief, Relief

I'm a Dickens guy, so I appreciate the manner and voice of the storyteller, and Bradbury was a kind of architect of English sentences. He was in the masculine tradition of Hemingway, pounding out strong, solid sentences that made his stories things of weight to bear in your arms. His views of art and gender are perhaps "Romantic" or "old-fashioned" at times, but his imagination was nothing short of visionary. This was his great power and his great gift. When I read him, I see the nightmare aspect of our modernist fantasies, but I also see the hope and the proof of the power of the imagination to confront our monsters, self-created or otherwise.

Scott Garbacz, Editor-in-Chief, The Midnight Diner

There are a few irreplaceable voices, authors who have a certain tone and attitude that becomes a treasured part of oneself. Ray Bradbury was one of those for me, as important to my intellectual maturity as John Steinbeck.

Each story he wrote was a vision – often presented without judgment – of some present or future possibility of what humans could be. When the rest of the world struggled with the bitter realities of civil rights, he wrote a Martian landscape colonized by African-Americans tired of putting up with the bullshit of earthbound racism and inequality. He dreamed of a great slumbering sea-beast whose thousand years of loneliness were cruelly interrupted by a fog horn that emulated the sound of his mate. He threw out an image of a slimy spaceman following a literal Jesus Christ from planet to planet, hoping for financial gain but always one moment too late. He even transformed his age's darkest fear, turning the threat of nuclear holocaust into a baptism by fire in which much of our hatred, consumerism, and alienation was burned away, leaving behind wiser humans who must (as Cormack McCarthy would later put it) "carry the fire" of our greatest cultural gifts.

Through all of his contradictory visions, he ever reminded us that mankind's immediate future might be neither a glorious eschaton nor an inhuman machine of oppression, but rather an unpredictable adventure to be lived out with courage and compassion.

Jake Slaughter, Relief staff

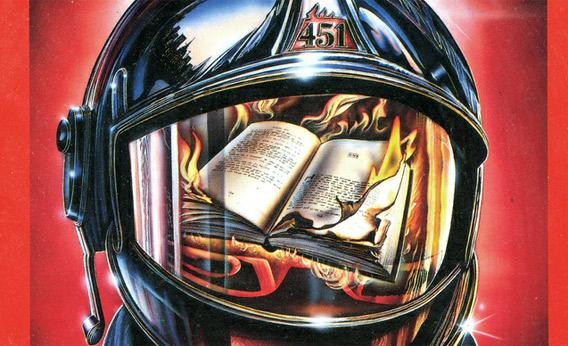

I first found Ray Bradbury’s work as I rummaged through the science fiction section of my local library during one of my middle school reading spurts. Nestled between two of the genre’s greats –Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke – I saw the eye-catching covers to paperback editions of The Illustrated Man, The Martian Chronicles, and Fahrenheit 451 and knew that I needed to read him.

When I was younger I was interested in the type of stories he told, but the thing about Bradbury is that he is more important than just the genre he helped to define. I look at his work now and realize how talented of a wordsmith he was. The paperback science fiction of the ’50s is known for fun narratives, not poetic writing. But Bradbury was a master of both.

Do you remember the point at the end of Fahrenheit 451 [mild spoiler alert] where Guy meets with the refugees outside of the city? As the war on culture begins again, these individuals have found a way of preserving the contents of their favorite literary works. Through memorization they are able to carry a work with them forever:

“Each man had a book he wanted to remember, and did. . . . We’re nothing more than dust jackets for books, of no significance otherwise. . . . And when the war’s over, someday, some year, the books can be written again, the people will be called in, one by one, to recite what they know. . . . But that’s the wonderful thing about man; he never gets so discouraged or disgusted that he gives up doing it all over again, because he knows very well it is important and worth the doing.”

Even when I was young this scene blew my mind. It is a brilliant statement on a reader’s role in culture. What we read and remember is carried with us throughout life. For Guy and the others in Fahrenheit 451, it becomes their identity. As a Christian, we might be reminded that the truths of the Bible are still communicated to us as a text.

I look and recognize that I am influenced by much of Bradbury’s work. I notice it when I read a piece of science fiction, or a short story, or when I consider the role of art in society. I carry his words with me.