How the Light Gets In

Rebecca Spears

Buildings are expressions of humans, of us. . . . they have eyes. Windows are the eyes on a building. — Michael Pollan, NPR interview, 19 April 1997

This past summer I had a cabin built in the woods—a place for weekends and summers, for visiting with friends, and for writing. Before the cabin was built, I spent some hours (agonizing at times) on the design of the small place. It is, after all, only 400 square feet, not including the front and back porches. For anyone to live well in a small space, the design needs to be not just efficient but also pleasing. While planning the cabin’s inside features, I also had to think about outside details. Design is an organic process: all the particulars are fundamental to the soundness of the whole structure.

Windows became one of the more significant aspects that I had to deal with. Windows are meant to work both functionally and aesthetically, as portals and barriers, as frames and passive light contrivances. Everywhere that I thought to place a window, to give me a view of the surrounding piney woods, I also had to give up wall space. I had to think about where the sun rises and sets because the cabin sits in a southern latitude where the summer sun is a bigger concern than winter’s weak light.

Before I began the process of cabin design and building, I read Michael Pollan’s A Place of My Own. Although I didn’t plan to build the cabin myself, I did have to think about what materials to use, where the cabin would sit, and how the site would be prepared. My thinking also ran to whether or not I could keep the cabin off-the-grid, and if not, how the cabin could be designed to use very little electricity. Windows, from this perspective, serve as an important source for heating and cooling.

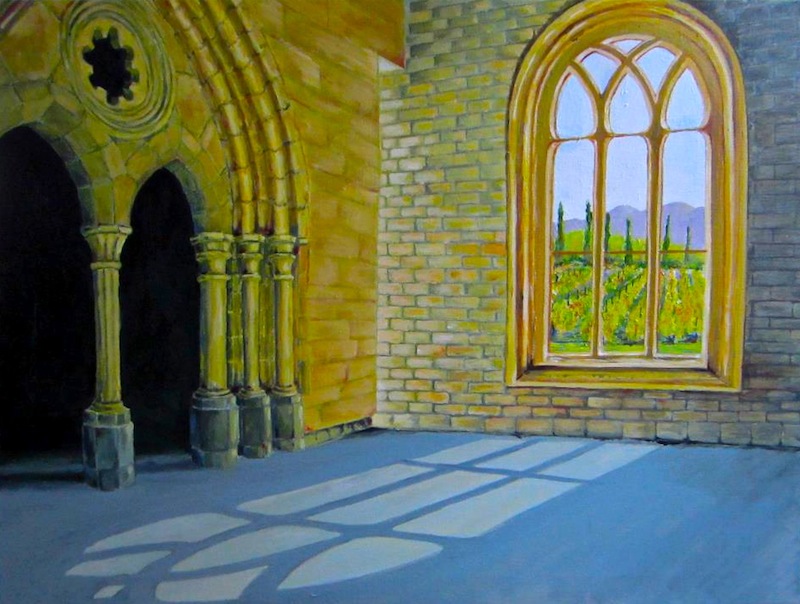

For me, the aesthetic function of windows is as significant as the environmental function. From the outside, windows add to the character and personality of a home. They are part of a structure’s face, as Michael Pollan notes. And I am drawn to clear panes of glass, not only in a house, but also in office buildings, stores, and churches. A long time ago, I fell in love with leaded glass windows in old houses and the way they divide the incoming light. It’s no surprise then that I also fell in love with the light of the “plain church” style when I attended a Congregational Church. The clear-glass windows provided perfect openings to use as a focus point during prayers and meditations.

Plain church style, with its clear windows, finds its precedent in twelfth-century Cistercian architecture. Because Cistercians believe that “prayer involves listening as much as asking,” their architectural principles emphasize “simplicity and an inner sense of quiet,” explains Thomas Davis, abbot of the Abbey of New Clairvaux. The early Cistercians built their monasteries of limestone with windows of clear glass. The light coming in through the windows is meant to link the monks to God.

Though I don’t have such high aspirations for my cabin, I wanted the windows to let in the natural light in a way that would frame the day and night and the changing weather patterns. So I chose clerestory windows for the southern face, and below them, large, divided-light windows—windows that when they are open will nearly erase the boundary between cabin and woods and let in generous breezes. In this way, I want to honor creation, the part of creation in my neck of the woods.