On Balance

Rebecca Spears

Your hand opens and closes, opens and closes.

If it were always a fist or always stretched open, you would be paralyzed.

Your deepest presence is in every small contracting and expanding,

the two as beautifully balanced and coordinated as birds' wings.

Your hand opens and closes, opens and closes.

If it were always a fist or always stretched open, you would be paralyzed.

Your deepest presence is in every small contracting and expanding,

the two as beautifully balanced and coordinated as birds' wings.

—Rumi

I teach literature and writing to students at a modern Orthodox Jewish high school. In a school where students take as many Judaic Studies classes as General Studies classes, they are regularly pulled from class for assemblies that have to do with holidays I am only beginning to learn about, even in my third year of teaching at the school—Sukkot, Purim, the Fast of Esther, Shavuot.

Parents enroll their students in our academy because the school mission proposes a balance between religious studies and academics. In fact, Modern Orthodox Judaism itself invites a balance between the life of the Jewish community and the life of the secular world; between religious observance and modernity (which includes academic studies); and between strictures and leniencies.

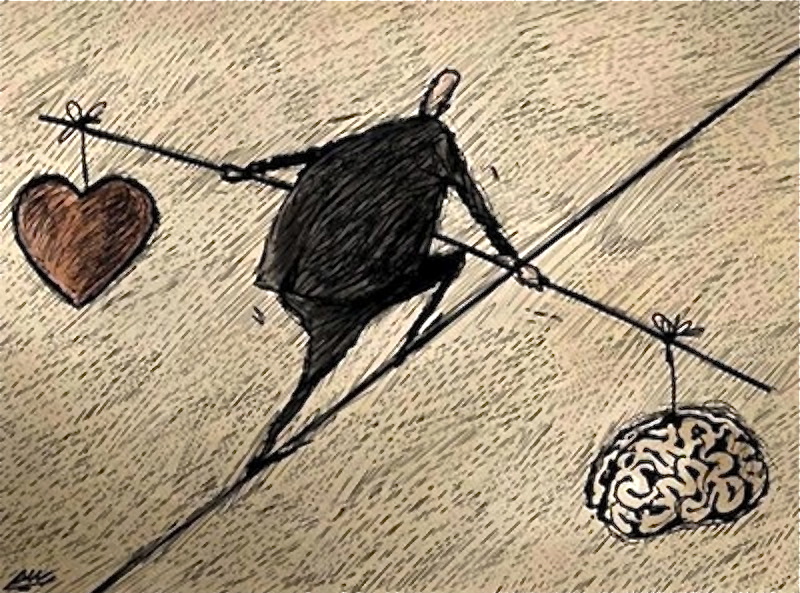

In terms of definition, “balance” is the result of two equal weights offsetting one another. Any extra weight added to one side disturbs the equilibrium. So the task to find harmony between religion and academics is necessarily delicate. Often General Studies teachers, myself included, proclaim frustration at the lack of time to teach a college preparatory curriculum to our busy students. Yet I know that my students will matriculate into colleges and universities based on their academic strengths; their Judaic classes “out there” in the secular world will be evaluated as “electives.” And so we have this argument always in play at the school—especially when students are pulled from class for assemblies—as to whether or not Judaic Studies are being privileged over General Studies and vice versa. All teachers, whether academic or Judaic, are constantly working to persuade the other “side” as to the value of our classes.

And yet I have to admire my students and colleagues who seek to weigh religious life with secular life. If pressed, I would say that I am a modern, progressive Christian. Lately, I have been seeking equilibrium in life similar to the Modern Orthodox Jews. Being a teacher at this academy has made me aware that while “balance” may look static, it is an active state. In contrast to Modern Orthodox Jews, I am coming at the problem from a decidedly different perspective because my life frequently feels defined by heavy engagement in the secular world, with a little spiritual activity on the side.

Not long ago, several friends introduced me to the work of the Franciscan priest, Richard Rohr. He advocates finding balance by setting aside time for contemplative practice daily, either early in the morning “before your brain has a chance to begin its list-making and judgments,” or in the evening, when you might examine the “God-encounters during your day.” This is the sacrament of Sabbath, which, he tells us, is “offered by the Jewish people as a gift for all humanity.” The sacrament of the Sabbath means surrendering one-seventh of your life to resting in awareness of a sacred presence. This practice makes sense to me, a way to give symmetry to my spiritual and secular lives. While I am usually averse to New Year’s resolutions, I am going to try to incorporate more contemplation into my life this year, an offset to my daily concerns.