Power of Meditation

Joy and Matthew Steem

Is it possible that William Fisk, the arch-villain in Marvel’s Daredevil TV series, admired Thomas Merton? That was the thought that came to my mind after hearing him look down at the nearly dead hero, Matthew Murdoch, and calmly state, “I find it difficult to meditate. My mind won't quiet. It’s a character flaw, I suppose.”

Is it possible that William Fisk, the arch-villain in Marvel’s Daredevil TV series, admired Thomas Merton? That was the thought that came to my mind after hearing him look down at the nearly dead hero, Matthew Murdoch, and calmly state, “I find it difficult to meditate. My mind won't quiet. It’s a character flaw, I suppose.”

Touché Mr. Fisk, touché.

I also took much pleasure from the fact that it was the bad guy who was saying that. Now I know for certain that the writers didn't put that line there for no good reason. They, like so many of the TV shows of the day, are also trying to educate their audience in some way. But while in many cases it’s a bit cheap— take for example the continual mawkish jabs which the TV series Elementary takes at tobacco and car idling—I was quite moved at such a nicely delivered snub to a more rooted problem in our culture: the near aversion to silence and its sibling solitude.

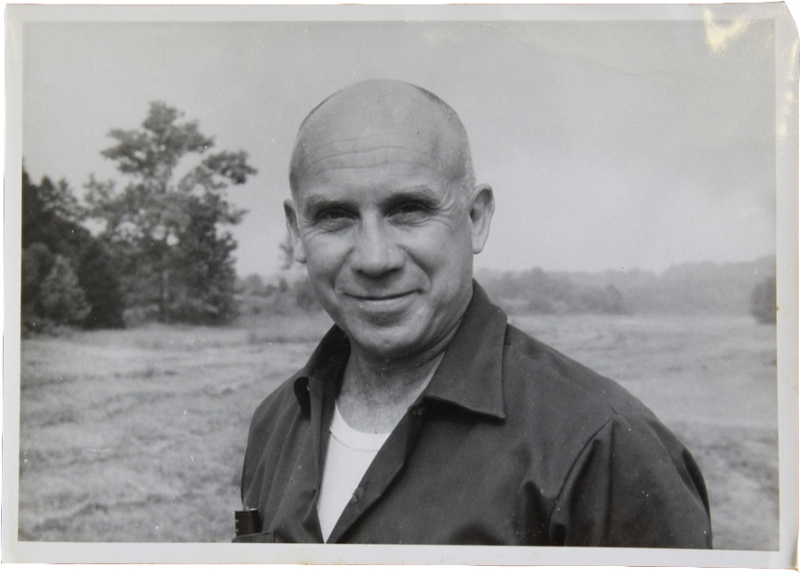

So you probably can see how Merton (contemplative extraordinaire) might have come to mind. And indeed, Merton would have probably had even harsher words about the near whole of our society being little able to quiet our minds than simply calling it a “character flaw.” Perhaps because while a character flaw is something that is individual, the near entirety of our society is antagonistic to a quieted mind. Yet at the same time, I believe Merton would have softly suggested that this perpetuation to an un-quieted mind is something that is remediable too, both in an individual and a society—though it might require more time and patient effort on the latter front.

So, first for the individual. It’s important to note that Merton believed that when it came to both solitude and silence, and the important role they play in our contemplative lives, people shouldn’t assume that it’s a topic only for monks or hermits. Rather, Merton made the strong case that a developed contemplative life is needed for all of us to live meaningfully and joyously.

Important to keep in mind is that solitude is assuredly not individualistic or rooted in desires for individualism. Merton says, “the true solitary is not one who simply withdraws from society. Mere withdrawal, regression, leads to a sick solitude.” That is to say, the person who simply seeks solitude to avoid the company of others will find a solitude that lacks both meaning and fruit. Indeed, for Merton, “false solitude separates a man from his brothers in such a way that he can no longer effectively give them anything or receive anything from them in his own spirit. It establishes him in a state of indigence, misery, blindness, torment, and despair.” The desire for true solitude will be best represented by “those who live for God, live with other people and live in the activities of their community.” Thus, “the true solitary does not renounce anything that is basic and human about his relationship to other men. He is deeply united to them.” In fact, in a later writing, Merton cautioned that “in prolonged separation from other men[,] there is a real danger of delusion and mental derangement.”

And just where best are we to find this solitude? Again, it doesn't lie in individualism. Merton clarifies that one certainly doesn't have to go out into the desert either: for “the desert does not necessarily have to be physical – it can be found even in the midst of men.” In fact, our contemplative guide assures us that “as soon as a man is fully disposed to be alone with God, he is alone with God no matter where he may be—in the country, the monastery, the woods or the city.” And so, back to Mr. Fisk, perhaps he is an apt reminder that without cultivating our capacity for the true solitude of inner stillness, we indeed risk endangering ourselves from experiencing the fullness of our humanity.