Macondo and Leota

Howard Schaap

Reading One Hundred Years of Solitude as an undergrad was the joy of the deep end of the pool. Ghosts, mysterious ascensions into heaven, ageless gypsies selling wonders to drive one mad, generations of family traits and vices that vine and tangle about us until we’re all firmly in the grasp of immanence. Into these strange and profound waters we were thrown and told to swim, and nobody was an expert, all of us floundered, tried to touch the bottom and failed, got worn out and doggy-paddled to the side for a break. It felt dangerous and new; it felt fun.

Reading One Hundred Years of Solitude as an undergrad was the joy of the deep end of the pool. Ghosts, mysterious ascensions into heaven, ageless gypsies selling wonders to drive one mad, generations of family traits and vices that vine and tangle about us until we’re all firmly in the grasp of immanence. Into these strange and profound waters we were thrown and told to swim, and nobody was an expert, all of us floundered, tried to touch the bottom and failed, got worn out and doggy-paddled to the side for a break. It felt dangerous and new; it felt fun.

Not long ago, I needed to write about my hometown, the same hometown I’ve written about a million times, the same hometown that we have oft dismissed with a wave of the hand around the table at family reunions. The writing was flavored by this humdrum shortsightedness. It was that small town with those same old gossip and false gods.

Not only was this description of the place false in its genericity, it was against a personal philosophy of mine: no small town, no landscape is exactly the same; each needs to be recognized for its nuance and character apart from our stereotypes of places like it. Simply put, I needed to see the place with new eyes.

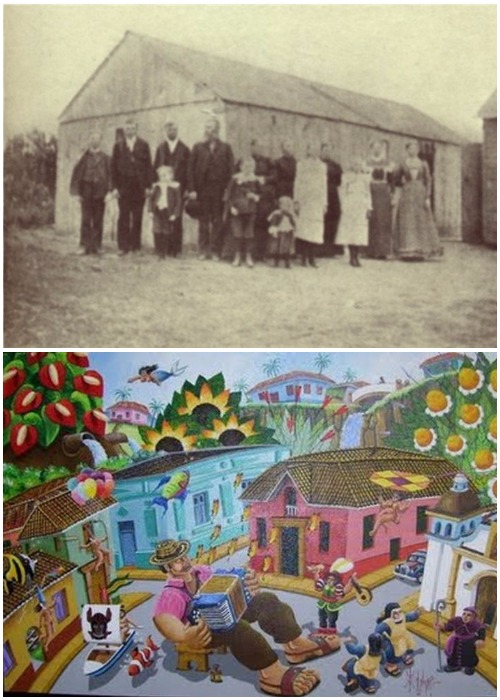

So I thought, what would Gabriel Garcia Marquez do? What about this small town, Leota, Minnesota, is Macondo-like?

The short answer might be nothing. Setting does matter; Minnesota prairie is not Colombia rain forest. Then, too, the belief system is different; a certain calculating realism of North America may simply iron the magic out of life with the tall grass. Remove 99% of the local ecosystem and see what happens to the magic in your neighborhood.

However, every place has its leveling forces, its conspirators against belief and wonder and hope. The artist has to have the power to follow the roots of these things deeper than simple pettiness of persons or pervasiveness of ideology. This is what makes Garcia Marquez’s vision so stunning. It’s so rooted in history that it’s mythic. And magic.

So, okay. Take a central image of village life for me. For his birthday, we would give my frugal grandfather a bottle of Mogen David wine. A sort of mischievous smile would spread across his face momentarily before being replaced by a more solemn one. Rising on shaky feet, he would close the window shades, lest the neighbors pass by and see him drinking a glass of wine on his birthday.

But what else was a-loose in the streets that Grampa was keeping out? Had the ghost of the man said to have been killed in a bar fight by my great-great grandfather trailed the family here, to the backstreets of Leota, from the Netherlands? Had the Huguenot martyrs, from even deeper in the family line, two languages removed from the English in the room? When you invite in the great cloud of witnesses—and when you make those witnesses, for the sake of story, the undead—suddenly the place takes on a whole new tone.

When I thought of the place this way, something sparked.

Then I texted my sisters. “Sibs,” I said, “I need colorful characters from Leota. I know you remember some, so . . . go!”

The exchange went on for hours. There was the wandering prophet selling Jerusalem artichokes whose magic crop withered in the fields as soon as he dissolved on the horizon. The substantial piano teacher who lived in the hardware store, big enough to divide herself in two and teach lessons in the back while serving customers in the front. The lone organist who played at her own funeral like everybody knew she would. There were divining rods and town festivals with angels and gypsies and dead men that wouldn’t lay down and families with fifteen children all with different colored teeth.

Not so un-Macondo-like after all.

And not so made up.

All of the magic was in the stories already, I just had to listen.