The room (she looked round it) was very shabby. There was no beauty anywhere . . . Nothing seemed to have merged. They all sat separate. And whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her.

The room (she looked round it) was very shabby. There was no beauty anywhere . . . Nothing seemed to have merged. They all sat separate. And whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her.

We remove the low table from its place in the entryway, fold out and lock its two sets of legs, and place it on the area rug in the center of the living room. The table is inlaid with a fancy-looking peacock, but the plastic white edging is now almost completely broken off, and even the glossy surface is cracked and beginning to reveal the particle-board realities underneath. We accumulate mismatched sets of silverware and plates and water, a jug of water, and a roll of paper towels for napkins.

It’s August, the doldrums. People are dying: an elderly neighbor, a man from bible study, to say nothing of world terrors. With the frenetic academic year looming, there’s no telling how our family, together for the moment, might fragment.

. . . an exquisite scent of olives and oil and juice rose from the great brown dish as Marthe, with a little flourish, took the cover off. The cook had spent three days over that dish. And she must take great care, Mrs. Ramsay thought, diving into the soft mass, to choose a specially tender piece for William Bankes. And she peered into the dish, with its shiny walls and its confusion of savoury brown and yellow meats and its bay leaves and its wine, and thought.

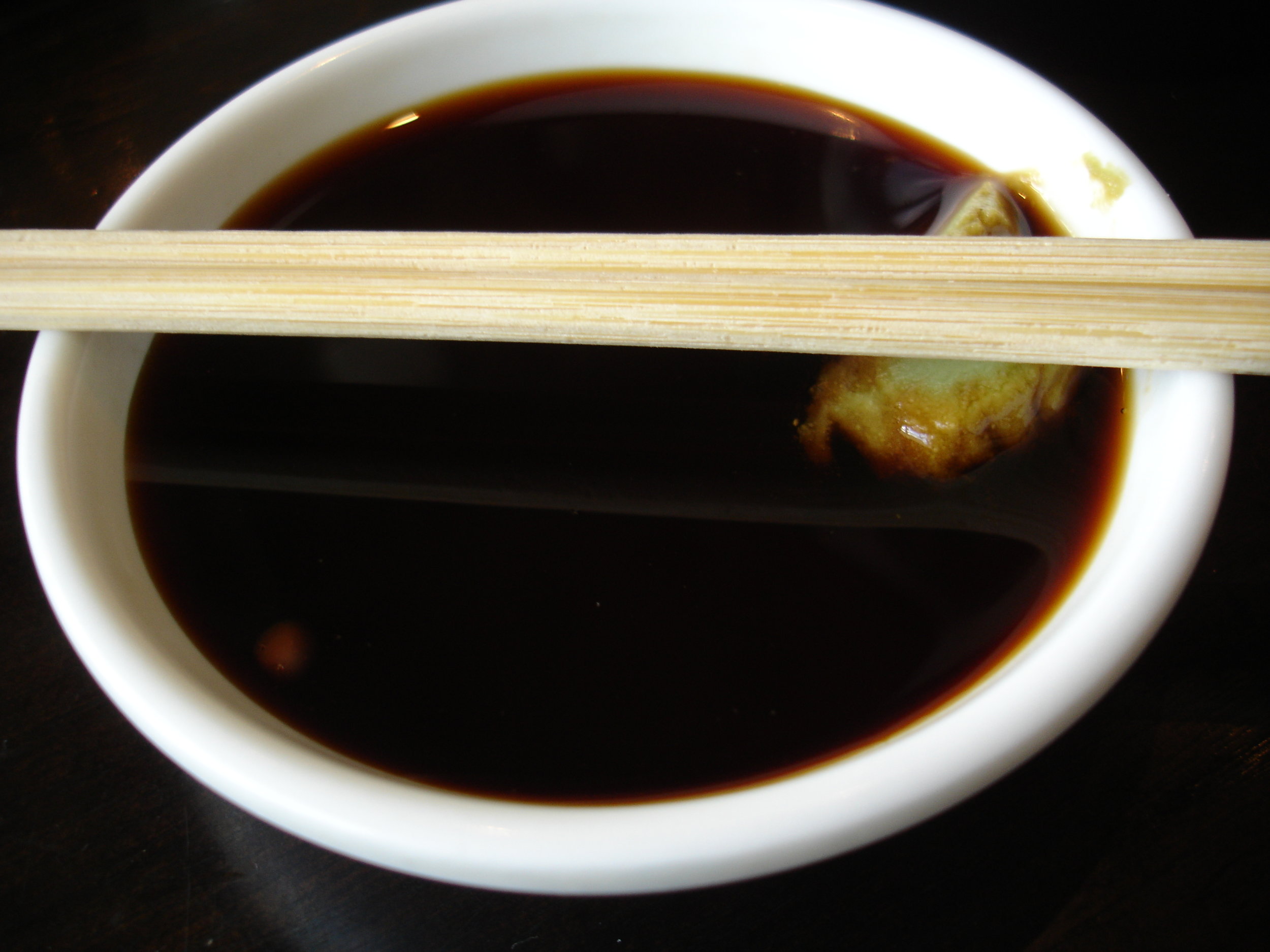

The meal is a drawing together, as all meals are, an orchestration. The jaew bdak, a spicy fish paste, comes from minnows Keo salted and allowed to ferment for weeks in a pail under her table, salting and turning it until it became something powerful and lasting.

The two kinds of sausage, spicy and not, were made by a friend, given within the transaction of friendship that’s really a window between hearts allowing for the free exchange of goodnesses, tomatoes for sausages, without accounting.

The pak bone, the English name for which I can’t find even on the Internet, is a Lao vegetable we coddled through a cool spring while Keo was away, distinguishing its frail leaves from among the spurious seeds which combust spontaneously from soil.

Two types of long bean, the usual green type and a beautiful purple long bean, that someone on Facebook identifies in Chinese and Bing translates to cicada beans. These, too, are called up from the garden, as if the smell of the sky and the weight of the air made this the perfect year to grow them.

Sticky rice from Thailand in a bamboo basket.

Nothing need be said; nothing could be said. There it was, all round them. It partook, she felt, carefully helping Mr. Bankes to a specially tender piece, of eternity; as she had already felt about something different once before that afternoon; there is a coherence in things, a stability; something, she meant, is immune from change, and shines out . . . in the face of the flowing, the fleeting, the spectral, like a ruby; so that again tonight she had the feeling she had had once today, already, of peace, of rest. Of such moments, she thought, the thing is made that endures.

The meal is a part of Keo, my mother-in-law. She’s drawn forth the frail pak bone by sheer force of will, stir-fried the dark green leaves and tougher stalks at full length so you have to wrestle with them, know their full being as you eat. She’s similarly ministered to the beans as they lengthen on their fence. Now, these are smashed in a mortar (koak) and pestle (sakk), again in a way so as to know their texture and fresh taste: the dry, earthy juice of beans among the sweetness of cherry tomatoes, the salt of fish sauce, garlic and Thai peppers on their way from green to red.

This August meal with Keo and the one orchestrated by Mrs. Ramsay in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse are aesthetically and materially different, there’s no doubt, but both share a beauty rooted in care that opens onto something greater. The placement of the purples and reds on the backdrop of greens in the bean dish; that dish flanked by the light colored sausage, the dark green pak bone, the pale warmth of rice, the light ochre jaew bdak—it works upon us this August, a meal, a piece of eternity.

I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in

I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in  It usually doesn’t happen until about mid-journey. Up till that point, the sun has been up, and you can see where you’re going. You’ve never been in this kind of car before, and you like some of the buttons and the scenery outside your window—old barns or even the edges of industrial wastes—and just the experience of being in the passenger seat and wondering where it is you’re going. The driver has a hypnotic voice and quirks that are fascinating; a tattoo runs down the side of his neck—“R-A-” something.

It usually doesn’t happen until about mid-journey. Up till that point, the sun has been up, and you can see where you’re going. You’ve never been in this kind of car before, and you like some of the buttons and the scenery outside your window—old barns or even the edges of industrial wastes—and just the experience of being in the passenger seat and wondering where it is you’re going. The driver has a hypnotic voice and quirks that are fascinating; a tattoo runs down the side of his neck—“R-A-” something.![By Thesupermat (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12239656ca13c4525ec5/1487540771195/Pilate-Gesture.jpg?format=original) It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.

A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.  I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world.

I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world. This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question: It can’t make sense everywhere. I assume it has a temperate climate bias. Or, to be more precise, a four-season climate bias, yet it’s arguably one of the most lasting pieces of colloquial insight bequeathed to us from the recent past: “March comes in like a lion and goes out like lamb.” Or vice versa. That’s the allure of the phrase, I think, its seesaw mechanics. Pay attention to this one month, this little adage promises us, and you too can predict the weather. It’s tempting to make weather simple. The weather in any given place is distillable to a few features, to northeasters and lake-effect snow and Santa Ana winds. Where I live, any given day is likely to be ruined by wind, first and foremost from the northwest, straight out the arctic, and second from dead south, straight out the furnaces of hell.

It can’t make sense everywhere. I assume it has a temperate climate bias. Or, to be more precise, a four-season climate bias, yet it’s arguably one of the most lasting pieces of colloquial insight bequeathed to us from the recent past: “March comes in like a lion and goes out like lamb.” Or vice versa. That’s the allure of the phrase, I think, its seesaw mechanics. Pay attention to this one month, this little adage promises us, and you too can predict the weather. It’s tempting to make weather simple. The weather in any given place is distillable to a few features, to northeasters and lake-effect snow and Santa Ana winds. Where I live, any given day is likely to be ruined by wind, first and foremost from the northwest, straight out the arctic, and second from dead south, straight out the furnaces of hell.