The Woman Who Was Chesterton: Where Did the Spouses Go?

Joy and Matthew Steem

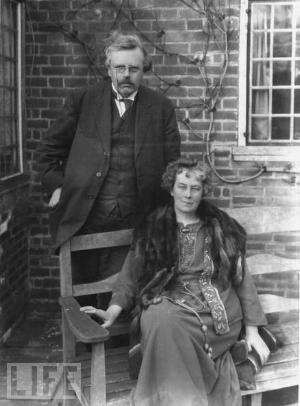

Frances Chesterton with G.K. Chesterton.

I have been an avid fan of G. K Chesterton for a number of years. I have read numerous biographies, perused through his essays, novels, short stories, and poems, and found them all bright and useful. I had no complaints with the biographies—until now. Enter Nancy Carpentier Brown’s The Woman Who Was Chesterton (2015). Suddenly, I realized that my knowledge of Chesterton was lacking, and in a big way: I didn’t know much about his wife, Frances.

And while she wasn’t as large as he, either in physical size or reputation, after reading Carpentier Brown I came to appreciate that I hadn’t given her the respect that she was due. Not necessarily directly in the literary world, but what she contributed to making her husband’s literary yield a possibility. Previously, I had only been let in on an aspect of Chesterton, but by not knowing more about Frances, my understanding of him was limited.

I think, to a large degree, many of the biographers didn’t touch on her much because of the accepted historical view, which minimised the role of the home and of the nurturing that happens there. Ergo, the role of homemakers also got cut. What was important was the big ideas, the meeting of the big people—mainly men—and the big influences that these big men had on society (whether that was in politics, religion or whatever). However, what this excluded was “the little things” which were contributed by the spouse. In her book, Carpentier Brown demonstrates how Frances’s attention to detail in the home (this included the cooking, taking care of animals, which, among others, included chickens and a donkey) compounded the happiness of both Chestertons. And while Frances may have well enjoyed keeping a memorable flower garden (which G.K loved romping through), she also had to attempt curbing G.K’s diet: this sometimes put her at odds with his doting mother. In other words, Frances was responsible as her husband’s primary caretaker. The joke was that G.K. was her job.

If it wouldn’t have been for Frances, it’s likely that along with not showing up for lectures and appointments of varying types, G.K. might not have come fully clothed or bathed. If it would not have been for her, there simply wouldn’t have been the Chesterton that I know. This is an unquestionable fact.

Previous to reading The Woman Who Was Chesterton, I had known a slightly different G.K. Chesterton. Afterward, I came to a more Catholic version of him. And I say Catholic because in a faith based world we see that people work together, people create together, they rely on each other—in other words, they depend on the other to help them in their weakness. They are a community. In the Chestertons’ case, I learned that Frances and G.K. frequently discussed in-depth the concepts that would later show up in his published work. He believed in her poetic ability enough to endeavor to get some of her work published into the public sphere: some of which was awarded prizes. Finally, G.K never forgot that it was Frances who brought him to faith in the first place. This alone was worth more than the world—literally—to G.K. Truly, together they were stronger.