A Tale of Tweelie

Joy and Matthew Steem

This is neither ghost story nor a tale of suspense: it is a bit of writing about a bird teaching me insights that I should have learned a long while ago.

Read MoreUse the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

123 Street Avenue, City Town, 99999

(123) 555-6789

email@address.com

You can set your address, phone number, email and site description in the settings tab.

Link to read me page with more information.

Filtering by Tag: Joy and Matthew Steem

This is neither ghost story nor a tale of suspense: it is a bit of writing about a bird teaching me insights that I should have learned a long while ago.

Read MoreI have been an avid fan of G. K Chesterton for a number of years. I have read numerous biographies, perused through his essays, novels, short stories, and poems, and found them all bright and useful. I had no complaints with the biographies—until now. Enter Nancy Carpentier Brown’s The Woman Who Was Chesterton (2015). Suddenly, I realized that my knowledge of Chesterton was lacking, and in a big way: I didn’t know much about his wife, Frances.

Read More“The body interacts and changes places with apparel as we wear it, changing ruffle to ankle, in the vision of one motion. We let it affect the way we move, the way we interact, the way we shape affection, the means by which we negotiate other’s opinions of our social standing, the way we cognize our own body.”

—Daneen Wordrop,

As one who doesn’t typically pay a great deal of attention to the act of dressing, I have an ambiguous relationship with clothing. In fact, I often catch myself contemplating the necessity of clothing in negative terms, partly because over the years I have become increasingly aware of the class distinctions and identity communicating elements inherent in clothing choices. My mindset has been slowly changing though, in large part thanks to a generous benefactor of luxurious hand-me-downs.

Read MoreI remember the first time I experienced the blunt heaviness of homesickness: the pulsing desire to return to the place of belonging, to people who care, and an environment that’s safe. I was in grade two and had been away from my family for about five days at a non-profit kid’s camp a few hours away. Curiously, the wumping of homeward ache didn’t hit me until after arriving at my friend’s house, where I awaited mom to pick me up. Suddenly, less than half an hour from home, the telltale symptoms of loneliness started leaking out my eyes. I remember my friend’s gentle dad leaving a message on my parents’ machine, “come whenever you can, I think someone is quite homesick.”

Read MoreThe trouble with T.S Eliot’s reputation, many writers have said, is that his early work has been explored (think “The Wasteland”) while the later has been ignored. This has changed somewhat lately, but it’s still fairly pervasive. For example, in many poetry anthologies – the place where students get their first taste of poetry – it will be the younger, non-believing rather nihilistic Eliot they are introduced to. It’s not too often that something like the Four Quartets will be provided. Nope, the concluding sentiment received will be, likely, from “The Hollow Men”:

“This is the way the world ends (x3)

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

For a long while—years—an exceedingly good friend pestered me to read Graham Greene, specifically The Power and The Glory. When I finally made the right choice, I had a sense of loss—grief that had I read the work earlier, I may have been a more replete and insightful person. I now personally know why he has been called one of the better writers (and a Catholic to boot) of the century.

Read MoreWhile writing on such a grandiose personage, it’s hard to not aspire to touch on a great many magnificent things. And what numerous numbers there are! Ashamedly, I have not read much Coleridge before. I knew of him historically speaking, and what he was known for and with whom he hob-knobbed, but I had read little past “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and a few others. Then I landed his Aids to Reflection.

Read More

The best reason for a revival of philosophy is that unless a man has a philosophy certain horrible things will happen to him. He will be practical; he will be progressive; he will cultivate efficiency. — G.K. Chesterton

Any reader of Chesterton knows that he is quite quotable; however, sometimes his quotidian nature can also stump and confound. Take the above for instance: while we can appreciate the need for good philosophy [think C.S. Lewis] what are we to do with the “horrible things” that Chesterton stands against? After all, in our culture isn’t practicality a good thing? And that goes for being progressive and efficient too, not?

We want practical money managers; progressive medical technology; and surely, efficient cars and refrigerators.

But it is not these things that Chesterton warns about.

G.K’s primary concern is that these traits become ends in and of themselves without reflection on their potential consequences. Take for instance his gripe about “a practical man.” For Chesterton, the practical man cares only about the final results of an endeavour (whether that be in business or politics or whatever) and not what took place in the interim (the steps which were taken to achieve the end result: an example would be the food industry using GMO food without considering the potential consequence). Chesterton posits, “When will people see the simple fact that practicality is a question of means, not of ends?”

For Chesterton, being practical is linked to being progressive. So back to the example of GMO: a perfect example of progress. Progressives look ahead to solve current problems without doing the hard work of fixing something now. A good example might be the average power consumer being unwilling to lower their power outage by 15%, instead trusting that the power companies will, with scientific aid, be able to simply reduce the amount of pollution that is created. Or, the desire to increase crop production through GMO – instead of tackling the uglier and slightly more work intensive trouble of consumer waste (stats proclaim that we waste between 30-40% of our food). Chesterton doesn’t approve of putting one’s trust in the future when we could take action now.

Lastly, efficiency itself is value neutral; as a tool it can be employed for either good or bad. Further, once turned into a process, it can be easily used for control. Most of us know that the Nazi death camps were pristinely efficient. It was this very efficiency which palpably made the death camps so heinous. Euthanasia is efficient as were the desired outcomes of eugenic programs. Less nasty examples were the assembly line productions which turned workers into automatons. Efficiency is a means, but it is not an end in itself. It’s a handy tool that can make our lives better, but it must be placed in its proper hierarchy—i.e. below us. Ultimately, Chesterton wants us to ascertain, whenever efficiency is employed, what is the end game? And whom does it ultimately serve?

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a McSweeny’s Internet Tendency entry that suggested a simple fail proof way of attracting (and keeping) more readers: insert GIFs of jiggling breasts throughout the text. For those of us who laugh, is there a ring of fatigued disillusionment in it? As song writers or poets or visual artists or composers our creations feel sterile without some type of social interaction, or at least recognition. Having an audience is nice.

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a McSweeny’s Internet Tendency entry that suggested a simple fail proof way of attracting (and keeping) more readers: insert GIFs of jiggling breasts throughout the text. For those of us who laugh, is there a ring of fatigued disillusionment in it? As song writers or poets or visual artists or composers our creations feel sterile without some type of social interaction, or at least recognition. Having an audience is nice.

We yearn to connect. It chafes the less mature of us when we see mere scandal and spectacle reap a harvest of readers/watchers/listeners that objects of genuine artistry are likely to never see. Ever. The mean-well people (often non-creatives) who empathetically suggest a genuinely creative spirit doesn’t need any sort of audience because the joy rests in the act of creation are, well, wrong. (In part, Jacque Maritan’s reminder that true creativity is not mere self-expression or cathartic release of personal feelings; rather, it is the building of something for its own good, seems to make sense here.)

We are an interactive people. It’s not mere egotism which drives our desire for communicating our work; it’s the desire to connect, to grow, to truly communicate. This impulse to share is not one that should be repressed or bemoaned, but rather one to be celebrated because it reflects the desire for communion with others. In God Has A Dream, Desmond Tutu relates the concept of ubuntu beautifully: “[ubuntu] does not say, ‘I think therefore I am.’ It says rather: 'I am human because I belong. I participate I share.’” This insight is especially pertinent for us in a culture that, despite all our communication technologies, urges us towards isolation and the tendency to see success as the achievement of ultimate independence.

In a lecture on virtue based ethics, Bill Dejong suggested that there can be a sinful element in the “in the comfort of your own home” culture. (I.E “Enjoy theatre or gormeau cooking or symphony or whatever in your own home” that we hear from the advertisers of giant television screens etc.) He suggests that to deliberately participate in practices of isolation is to indulge pride: pride that we can be happy and fulfilled only with ourselves—that we don’t need the participation of others in our emotionally, spiritually, and perhaps even physically, isolated lives.

I’ve been thinking that creativity, with its deep longing for resonance, perhaps, could be part of a solution for the dehumanizing idealization of the isolated hero. After all, creativity yearns for relationship, for response, for connection: for the acknowledgement that we are human and that we belong.

Read Part 1

Read Part 1

For Josef Pieper, leisure is certainly connected to the older Platonic and Aristotelian concept of leisure as contemplation; however, it’s more than just that. For him, in the classical sense, leisure was something tied to the liberal arts: human activities that are separate from the servile works (those works that have a utilitarian purpose) and which have an end beyond themselves—a practicable, utilitarian result.

But leisure is not merely contemplation. Pieper calls it "a mental and spiritual attitude" and "a condition of the soul” that goes against the "exclusive ideal of work as activity.” Instead, this attitude is one “of non-activity, of inward calm, of silence; it means not being busy but letting things happen."

It is possible that some may read Pieper’s views and wonder if he considers work ethic alone as a bit … shallow. Is he saying that leisure ameliorates a working life?

No indeed. Yes, Pieper believes leisure can restore a person’s mental, physical, and even psychical state, but its impact is far greater than that. He goes so far as to call leisure “the power of stepping beyond the workaday world, and in so doing touching upon the superhuman life-giving powers which, incidentally almost, renew and quicken us for our everyday tasks.” He sees leisure as a means to opening the “gate to freedom,” where one can escape the world “where work and unemployment are the two inescapable poles of existence.’”

Many times we do not attain leisure precisely because we haven't a clue about the function of work and what humans are actually placed on earth for. It is a confusion related to issues such as materialism and consumerism.

When another excellent author, Sebastian de Grazia, was asked what his book Of Time, Work, and Leisure was about, he said his questioners laughingly had responses such as: “when you find out where to get it, let me know, because I desperately want some.”

To read Pieper is to rediscover “the point and the justification of leisure.” It is ultimately a pursuit of wholeness.

To be human is to be whole; and work alone will never make us whole. Work is but a part of our life: it contributes to our needs. However, it is never an end. Pieper tells us that if we feel that we must always be working, it may

be ultimately due to the inner impoverishment of [that] individual: in this context everyone whose life is completely filled by his work ... has shrunk inwardly, and contracted, with the result that [he] can no longer act significantly outside his work, and perhaps can no longer even conceive of such a thing.

This last part “and perhaps can no longer even conceive of such a thing,” seems to speak to many of our culture, no? How tragic. Thomas Merton, who loved silence for its stilling and centering effect, spoke against the seeming need of our society to dull our real human desire to be whole. He saw noise as an opiate.

We want noise because we are not comfortable—yet we know something is amiss. You will probably recall that Pascal spoke of this a long while back: “All human unhappiness comes from not knowing how to stay quietly in a room.” Pieper speaks to the silence issue as well. He tells us “leisure is a form of silence, of that silence which is the prerequisite of the apprehension of reality: only the silent hear and those who do not remain silent do not hear.”

And so back to the initial assertion about work being divine, and to repudiate it is to commit suicide. This is partly true. We are to take value in work. But this is not the ultimate conclusion of our life. We are to live, and to know why we live requires leisure.

Work is divine. God is revealed as the great worker and it is through work that men become like God. It is through work that man finds his life and his life is measured by his work ... to run away from work is to run away from life. To repudiate work is to commit suicide. —Gus Dyer, columnist in the 1930s

Many times the happy benefit of belonging to a certain nationality is that one can riotously criticize it, where otherwise it would be sacrosanct—and worse, politically incorrect! Anyway, coming from a rural German Protestant family I know a thing or two about a work ethic. Cleanliness might be next to Godliness, but work is even holier than soap. “Idle hands are the devil’s workshop, right”? Ever since being young enough to remember, a pristinely praiseworthy comment was, “oh my, but that person is a good worker.” And when that worker was me it was enough to motivate the righteous action of “putting one’s back into it” even more.

Oh yes, you could know a person by their fruits. In fact, chances were that if those fruits reeked of sweat and toil—Jesus was totally happy too. After all, you will remember scripture commanding, “do it as unto the Lord” (i.e. the Lord wants your all) and do it with all your strength (with that I would ask myself, “would Jesus be ok with just an 8 hour workday?”). If doing for God and with all your strength wasn't enough, the proviso was added, “do it without grumbling and complaining too” (you wanna argue with Jesus?!! Now get back to work, slob! ... after all Jesus went to the cross for you).

God bless my grandmother, but even when it comes to potential relationships, work ethic is one of the first questions asked. “Is this person a good worker”?

Thanks grandma.

And so I was stilled for a moment when I read “have leisure and know that I am God” in Josef Pieper’s Leisure the Basis of Culture (which has an excellent introduction by T.S. Eliot, by the way).

The search engine in my mind came up with nothing like that in the scripture I had read. I had never heard that verse before. (This will show my lack of Catholic bible tradition.) Trusting Pieper’s credentials, I went on to one of the most contrary ideas I had come across in my German upbringing, and it was written by a German none-the-less! Stupendous.

So what of grandma’s high valuation of a good work ethic? Well of course a good worker is something to be valued. If you have read Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism you will have read that capitalism itself has been greatly shaped by it. (It should be noted here that good ol’ Weber was prone to cherry picking quotes—a horrid thing—and his thesis actually shouldn’t be taken quite as serious as it is, considering proper historiographical methodology.)

Pieper is not against work itself—in fact, he says that you can't have leisure without it! —however, he asserts, since God’s creation is good, our enjoyment is of the utmost to God. And of course enjoyment is not merely efficiency or production. It can include that, but those things in themselves aren’t ends. Ultimately, it is ends with which Pieper is interested.

Enter leisure.

To be continued tomorrow.

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with G.K. Chesterton quite some time ago, but I didn't. The surprising insight was that he was, like, actually, friendly.

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with G.K. Chesterton quite some time ago, but I didn't. The surprising insight was that he was, like, actually, friendly.

I was introduced to a Chesterton who was so cool a cat that he could trounce any erroneous and ill-conceived ideology: political or religious or anything else which might stand in the way of orthodoxy. This Chesterton destroyed the proud scientific triumphalism of H.G. Wells and Huxley (think eugenics), the utopian dreams of Shaw, and other secular humanists of his time. This giant, mentally and otherwise, trounced the materialists and atheists with blasting wit and withering humour. To be truthful, I originally read the man in the following way: I searched for a topic that I disliked and then would try to find an essay on which Chesterton criticized it. (This is a wretchedly shameful thing, and I have since repented heartily.) Of course, generally if you look for a thing, you can find it. But it’s just not the right way to go about it. But everybody knows this, so I will move on.

I suppose I might have seen Chesterton as the Crusader—sword of truth in hand, gleefully excited to bloodily slay the perfidious untruth—in light of him being introduced to me as an apologist. This is one of the troubles with some Christian apologetics: it seems that often the desire to be correct is more important than that the apologist demonstrates a loving alternative to an error in reason, however, that's another topic. Anyway, I read how Chesterton had, with short shrift, dealt with the heretics of his day. To make matters worse, I read some of his more popular works (Orthodoxy, Heretics, What’s Wrong with the World and others) through that lens: tinted with impatience, brute force and pomposity. And of course, sometimes when having a crusader mentality, that seems pretty cool!

Yet, having read more of the man, I see that my early assumptions were about as far out to lunch as ... well, I don't know what. I was just really wrong. Chesterton was actually hugely humble, rarely took to an uncharitable offensive—according to most who knew him and all the biographers—and was exceedingly gracious. He also took the time to understand thoroughly the arguments of his opponents—a thing that Thomas Aquinas would approve—and tried to always gain some type of common ground with an opponent.

Moreover, unlike debaters of our own time, Chesterton was actually friends with many of his opponents. Yes, he actually was. I mean no disrespect towards to apologists like William Lane Craig for instance, but I doubt very much that if Mr. Craig died, Hitchens (if he were alive today) or Dawkins or Sam Harris etc., etc., would offer the widow financial assistance! Yet after Gilbert Keith Chesterton had passed away, this is exactly what Shaw did. During his lifetime, his opponents were truly his friends. And I wonder if this is why he was so persuasive in his life: because he was not wrestling against a person but rather an ideology. He loved people, and because his actions followed suit, people listened to him.

I wonder if today many of the apologist types—all of us—need to worry more about initiating conversation and friendship than in just being right.

It happened in the closing days of an expansive week and a half in Scotland seeing the awe inspiring ruins, breathing the thick Celtic air, rambling on the highlands and feasting on their startlingly fresh strawberries and unbeatable spuds. Settling into my early morning flight to London, I saw a ghastly image that has never quite left me: a spiny, mustard-yellow man whose grizzled body displayed with such shocking translucence the clawing effects of a life-sucking illness that the look at his decaying body arrested me with a terror so sudden and thorough that all human compassion was replaced with a gripping horror. I sat debilitated, crushingly ashamed and utterly terrified.

It happened in the closing days of an expansive week and a half in Scotland seeing the awe inspiring ruins, breathing the thick Celtic air, rambling on the highlands and feasting on their startlingly fresh strawberries and unbeatable spuds. Settling into my early morning flight to London, I saw a ghastly image that has never quite left me: a spiny, mustard-yellow man whose grizzled body displayed with such shocking translucence the clawing effects of a life-sucking illness that the look at his decaying body arrested me with a terror so sudden and thorough that all human compassion was replaced with a gripping horror. I sat debilitated, crushingly ashamed and utterly terrified.

Searching the caches of memories filed under “comfort,” I inwardly regenerated the likeness of Great Great Grandmother from George MacDonald’s Princess stories. Reassured by the gentle crooning that all worthy rockers make under the noble weight of maternal figures, I pictured Great-Great Grandmother sitting in her attic spinning: the splendour of her luxurious silver hair softening the sharper angles of her shoulders, her rich sparkling eyes evidencing shimmering wells of compassion and strength. At that moment, as I stood in the doorway to Great Great Grandmother’s attic, I knew she would welcome me to her side, despite, perhaps even because, of the weight of my shame and fear. She, MacDonald’s illustrious depiction of the feminine side of God, would call me to her warmth and envelop me with strength and courage.

The Princess stories were my introduction to MacDonald, and the image of Great Great Grandmother has been significant in my spiritual development. My head and heart have had a thorough plunging into the world of George MacDonald of recent. MacDonald's letters, unspoken sermons, essays, fiction, poems and biographies are in the process of burrowing into my heart and soul, much like a tick into the damp fleshy parts of a mammal.

This absorption evidences itself in several ways, I sometimes catch myself three bumpy lines into a sentence, hoping against hope to smooth out the rough waters of miss mashed consonants and commas, semi-colons and symbols all fighting for prominence. When this happens, my groan is swiftly followed with an optimistic sigh; I am pleased that MacDonald’s influence is consciously and unconsciously making its way into my inner workings. Although I don’t necessarily agree with the entirety of his world view, now that I know more about it, he has illustrated a more compassionate, gracious and loving approach to life. And, as such, philosophy, theology, personality and penmanship, when I see bits of it eeking out in my own work? Well, I couldn’t be more thrilled.

The world of written personal correspondence can be a tremulous one. I discovered this while in the preliminary stages of a questing romantic relationship. I was, not unkindly, told that the “real life me” was quite pleasantly different than the more opaque “me in letters.”

The world of written personal correspondence can be a tremulous one. I discovered this while in the preliminary stages of a questing romantic relationship. I was, not unkindly, told that the “real life me” was quite pleasantly different than the more opaque “me in letters.”

Now, this judgement had nothing to do with how or in what light I presented myself, but the way I presented myself. In print, it was gently suggested, it seemed I may have felt the urge to prove prowess and hide true meanings in complex language and ideologies—trying to demonstrate ability rather than authenticity. In my letters, it seemed to my correspondent, I took pains to veil myself: to create complexities of meaning that, in real life, were an illegitimate representation of the real time me. This suggestion, though not intended to hurt, did indeed cause much troubling self-doubt and questioning of my abilities and motivations as a communicator. In truth, I was not trying to flex an amateur writing muscle, and I was tender that the attempt to bare my soul and thoughts in letters was interpreted as mere posturing. Many maturing persons learn to cultivate the painful experience of being misunderstood into fodder for genuine flourishing: leaning with greater trust into the true self and the Person from whom it has been forged. Perhaps it wasn’t the complete misunderstanding that I had earlier hoped, though. In this case, I have wondered for years if those letters belied an unconscious belief about what the important stuff is: the stuff which deserves to be written about.

There are limitations to words on a page, of course. We all know what these are: turns of words and phrases shorn of tone, facial expression or body language. It seems in this age of communicative technology we have aids to visual transparency—though if our relationships are richer for it I am in great doubt. But this is not a diatribe on the dying art of penmanship; it is a meditation on what I learned of George MacDonald the man through his letters.

I started out expecting to learn some behind the scenes information about his theology, approach to composition, relationships and outlook on life in general. And while I did get some glimpses into these issues, what I really gained was perspective on MacDonald as a human being. A man who started a great deal of his letters with phrases like “I am ashamed to see by the date of your note how long I have delayed my answer” or “I am dreadfully busy, and carry a conscience oppressed with letters unwritten.” MacDonald the sufferer: a man often afflicted at various stages of his life with lumbago, back aches, abscesses, asthma, pleurisy, bronchitis, sleep disturbances, poverty and loss. MacDonald the requester: the hopeful often asking for help, whether monetary, materially or for a recommendation from a person of influence. MacDonald the friend: the writer of hope filled birthday wishes and heart filled condolences, gratitude rich thank you notes and pain soaked news of personal loss.

Perhaps, unconsciously, I was hoping to discover a hidden artifact or a little known nugget of knowledge that would help me piece together his vision: instead what I saw was evidence of the merit he placed in the daily-ness of life. George MacDonald the man of personal correspondence was just that: a man. Of course, as a human saturated and consummated in the vast breadth of Love, these themes pervade his letters, but the letters themselves are not necessarily about them. The near ordinariness of his topics is compelling. I should, of course, not be surprised by this because he did not reject the stuff our days are made of. He knew that no person is ordinary and no life is humdrum: we are children of “a live heart at the center of the lovely order of the Universe—a heart to which all the rest is but a clothing form—a heart that bears every truthful thought, every help-needing cry of each of its children.”

“Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

—Margaret Laurence, The Stone Angel

“Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

—Margaret Laurence, The Stone Angel

Last summer a friend and I pooled together some resources to cross half an ocean and take an elderly friend of the family on a day long excursion to a tourist attraction (we did other stuff when we were there too, so don’t esteem my altruism too highly). Not adept at planning, we took great care in organizing transportation, meals, operation hours, admission costs/requirements, mobility aids etc. On the way home from our pleasant outing, my friend asked the dozing but cognitively sharp octogenarian what was one of the most important things to living a worthwhile life.

The response? “Don’t ever go into debt. Save all your money.”

That’s it.

That was her advice.

In the months that have ensued I have been thinking a lot about the expectations we place on others, particularly the elderly. When I find myself frustrated with the ones in front of me, I often reach for the ones from literature for guidance. For me, one of these fictive individuals is Hagar Shipley from Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel.

Canadian author and literary critic George Woodcock recounts that the staying power of great literature in general, and Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel in particular, is related to its ability to depict universality as well as uniqueness. In Hagar Shipley, the increasingly dependent 90 year old protagonist, he says, we recognize enough aspects of our own grandmother that we have a certain sense of familiarity. Too much familiarity though, he warns, is tedious so all good authors also establish a degree of uniqueness which draws us in.

I’m not sure I see either of my grandmothers in Hagar, nor would I particularly want to. She treats others with harsh judgement, spite, resentment and a startling lack of insight. She assumes the worst intentions and is not easily entreatable. She is in fact, as her son refers to her, “a holy terror.”

So just what is it about Hagar that I find myself being drawn to again and again? What is in the recollection of this terrifying woman that revitalizes my patience and maybe even kindness when I find myself in the extended company of the aged? Perhaps it is my sympathy to Hagar’s dogged determination to the North American ideal of freedom (which, according to Margaret Atwood and others, defines her struggle). Or maybe, as Woodcock suggests, it is the loud grumblings and rumblings humanity makes along the path of mere survival. How can this story's startling reminder of mortality, human frailty, and tendency to egoism possibly encourage gentleness?

I think, for me, it is this: Laurence has entrusted something to the embittered and feisty Hagar that I sometimes forget to concede to people labeled “other”: humanity. Laurence has created a character with foibles and flaws and a striking sense of individuality. Hagar Shipley busts through the stereotypes we often place on the elderly: she is neither sweet nor kind nor senile nor particularly sagacious in a way we recognize.

And she, just as we, when asked “does one get used to life?” must shrug. She has not gotten used to life. Life, after all, is not a pizza or a bedspread. Life is not conquerable; it is not predictable; it is usually not even understandable. It just is.

Hagar’s tale is not necessarily a cautionary one, though she does eventually recognize that she has carried the backbreaking chains of pride throughout her life which has tragically “shackled all she touched.” I’m not sure Laurence means for me to pity Hagar, just as she does not entice me to emulate her. What Laurence does do is help me see: help me see the humanity in others and the humanity in me. And, while I am looking through that view, my capacity for compassion is enlarged.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Often, in an attempt to make me feel better, people will tell me that they are not very good with directions either. They mean well, but it doesn’t really help; it makes me feel like they think they understand, but they don’t. It can be somewhat isolating. So, when I meet someone who has a similar challenge it can be really quite bonding.

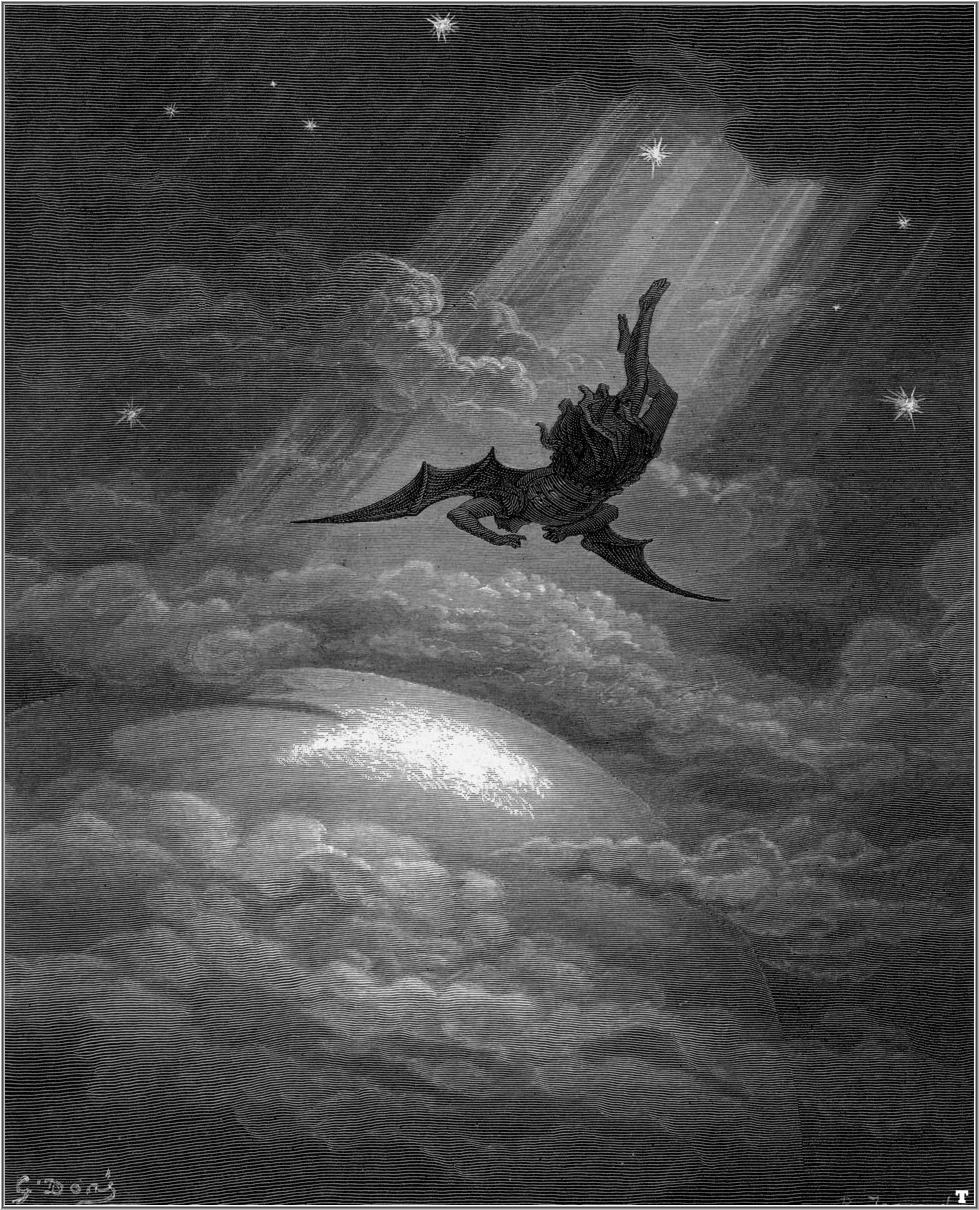

The petite elderly professor who taught me Paradise Lost was like that. One of her colleagues once told our class that said professor was so perpetually lost that it was sometimes an accomplishment for her to find her way home from a neighbour’s. True or not, the impression stuck and she became among my favorite instructors. When she spoke of Milton’s Satan, Adam, and Eve, I paid attention and was quite nearly riveted. Without power point, whiteboard, props or even a dramatic voice, the passages she pointed to were gripping. I still read it from time to time. The story fascinates me. I know the ending, how can I possibly be so transfixed, I sometimes wonder. I’m beginning to think I might have an inkling of what particularly fascinates me about the story: Satan.

Perhaps of all the lines in Paradise Lost, the description of Satan’s “stubborn patience as with triple steel” is among the most chilling for me. The Fallen Angel’s designs to deceive and destroy God’s freshly created Eve and Adam stuns me with its icy resolution. It strikes me because of its dissimilarity with the nature of evil that I often see portrayed in culture and literature: hot, passionate, sensual desire with searing results. Milton, however, shows us a Satan who is not sexy, only stubborn.

Like Francis Underwood of House of Cards, Satan’s plans are strategic, stealthy and unwearied: his will is enduring and his resilience indestructible. Perhaps this image is so striking for me because of the composed calmness the line suggests he possesses. There is little hustle and bustle going on at this moment; instead, there is cold calculation. Rather than the perpetrator of forbidden fun like the devil (who can forget Al Pacino in this role) in Devil’s Advocate, Milton’s antagonist embodies the nature of evil Charles Williams explores in Descent into Hell: deliberate, incremental and isolating steps that go deeper and deeper into the non-spectacular: the anti-spectacular, in fact, for it is oblivion.

The label “heretic” has such an interesting draw to it doesn't it. It holds a special charm for a variety of reasons I think: it’s generally anti-conformist, anti-populist, and anti-status-quo. That makes it unique, and unique can be quite attractive. Since everybody wants to be unique – especially in a culture of conformity – what’s not to like about heresy. Plus, it’s not all bad either. T. S Eliot spoke of it more than once and in some cases of it as a good. Anyway, all that to say that a label of something being potentially heretical makes it ... could I use the word “hot”?

The label “heretic” has such an interesting draw to it doesn't it. It holds a special charm for a variety of reasons I think: it’s generally anti-conformist, anti-populist, and anti-status-quo. That makes it unique, and unique can be quite attractive. Since everybody wants to be unique – especially in a culture of conformity – what’s not to like about heresy. Plus, it’s not all bad either. T. S Eliot spoke of it more than once and in some cases of it as a good. Anyway, all that to say that a label of something being potentially heretical makes it ... could I use the word “hot”?

So when I heard that one of the popular Inklings other than Lewis and Tolkien had it suggested of him that it would be understandable to have him burned at the stake, I was quite taken. “Cool,” I thought to myself. But then, because I was young I had a difficult time in reading Charles Williams. However, some years ago I came back to him and was most heartily surprised. And sure enough, the heresy claim isn't too far off. So of course I read him all the more. Now it’s not all that un-orthodox, but there are some interesting thoughts he brings up.

Just recently I was re-reading his second last novel, Descent into Hell, and found something interesting concerning his thoughts on Sodom and Gomorrah. Nope, it’s probably not what many others might be thinking (we here at Relief are a clever bunch). These two cities are connected for Williams with un-neighbourliness (which for Williams was a form of sterility in that it doesn't contribute to generating life) and solitude, and their direct association with hell.

Now, since I have tendencies towards introversion, I was not just a little annoyed at the strong connection with solitude and damnation. Plus, have you ever read what early psychological theory – Jung was a little kinder – said about those who were essentially introverted? It was basically pathological narcissism. However, as I continued to read Williams I was quite taken with his ideas and began to have self-to-self conversation/conversion. (Ever have a conversation with yourself and afterwards noticed that your view changed – it’s cool right? It might be difficult, but I think we actually can change our own bias.) I was persuaded that Williams had made a great point about solitude being the pathway to damnation when it is mixed with selfishness. Thomas Merton, who spoke a great deal of the importance of solitude, went to great lengths to clarify that while solitude is exceedingly important, it cannot be practiced for the sake of the self. If self is the primary concern, then this solitude is actually wicked. And the reader is lead to seeing selfish solitude as the ultimate undoing for anybody when practiced fully as William’s work depicts. I won't spoil the ending of Decent into Hell, but I think the suspense factor would have Stephen King green with envy.

Back to solitude as selfishness though. I once remember hearing a respected minister say something to a largish crowd that s/he just didn't have much time to spend chatting with friends and others when invited out because the time would be better spent with God. You know how Jesus was known to be meek? Yah, I wasn't at that moment. I didn't know how to voice it, but it felt, well, selfish. I mean I get separating yourself from the hordes from time to time – Jesus did that too, after all – but Jesus also spent lots of time with people. I think there should be a balance. Holiness that excludes itself from public life – from being human – might not be as holy as it thinks. We were made to live in communion with each other: which means both, sharing and imparting life with each other. So, of course we need alone time – I demand it regularly – but I was gently warned by Williams cautionary tale that solitude can't be mixed with selfishness. Because that is real heresy – and it’s not cool.

“It tastes healthy,” my friend benignly replied to my increasingly inquisitive gestures in the church potluck dining hall. The substance before us had the color of chocolate mousse; it had the consistency of chocolate mousse; it certainly felt like chocolate mousse on the tongue, but upon taking a mouthful, it immediately introduced itself with that telltale vegan, no sugar added, and nutrients aplenty sensation. It wagged its tongue at the sweet sultry flavor that chocolate offers—no sir, this stuff boasted dates, avocados, and coconut milk!

“It tastes healthy,” my friend benignly replied to my increasingly inquisitive gestures in the church potluck dining hall. The substance before us had the color of chocolate mousse; it had the consistency of chocolate mousse; it certainly felt like chocolate mousse on the tongue, but upon taking a mouthful, it immediately introduced itself with that telltale vegan, no sugar added, and nutrients aplenty sensation. It wagged its tongue at the sweet sultry flavor that chocolate offers—no sir, this stuff boasted dates, avocados, and coconut milk!

Now, I actually have a pretty strong affinity for quirky health-filled kitchen concoctions. Pinto bean brownies, dessert hummus, beet breakfast bars with chilli peppers and cardamom, gingered lentil goji berry cereal: these are things that find their way into my edible creations. Someone might call my concoctions bizarre, but most nutritionally minded people I know would call them wholesome, or guilt free, or maybe even innocent: and they would mean it as a compliment. Still, though, there is no denying it, sugar-free, dairy-free, gluten-free food generally has that healthy taste about it. And to be honest, as a metaphorical concept, the whole healthy food versus yummy food dichotomy deeply troubles me. I struggle against the thought because as someone who aspires to a spiritually enriched life, I feel that the polarization relegates my pursuits to the healthy tasting section of the potluck table: the brownish, runny bland dish in a homely, well-used crockpot that people look at probingly before quickly darting to the next dish.

Several years ago I found it quite convenient to partake in an exclusively strict superfood laden regimen. I had some spare time on my hands so I figured taking the effort to prepare really healthy stuff would be a good experiment in how it made me feel. For months I ate sprouts, beans, kale, spinach and tofu—it was a banquet of nutrition packed awesomeness. And then a friend of mine, who happens to be an excellent cook, came to stay with me.

During the week together we feasted on homemade buttery shrimp bisque, Greek pasta salads that luxuriated in feta cheese and oil, crème brulee and cake so delightful that I could have written romantic odes to it. Meal after meal I quietly moaned to my friend, “I didn’t know food could taste this good.” Every meal was like a Dionysian festival betwixt my lips.

When my friend left and the culinary expedition ended, I felt as though I had two stark choices for restocking my refrigerator: sprouts or stroganoff. I approached my food choices as I sometimes subconsciously approach life: I could make the healthy and responsible choice or the delicious and enjoyable one. My mouth, accustomed to the sweet joys of butter, sugar and cream howled for satisfaction, my body, slightly sluggish but staunch, quietly demanded some veggies. I had to make a choice, there was only room for one.

What I am seeing more of is that, as a general concept, enjoyment and responsibility are not necessarily as dichotomous as I sometimes have been led to believe though. Surprising as it is to me, my pursuits can’t quite be compacted down to the category of a vegetable or a cake. This is particularly applicable to a nuanced spiritual perspective. In an excerpt of Miroslav Volf’s book, Flourishing: Why We Need Religion in a Globalized World, posted in Christian Century, he says:

In choosing between meaning and pleasure we always make the wrong choice. Pleasure without meaning is vapid; meaning without pleasure is crushing. In its own way, each is nihilistic without the other. But we don’t need to choose. The unity of meaning and pleasure, which we experience as joy, is given with the God who is Love.

This is truly magnificent news, for it tells me my dichotomy is off. Love personified has constructed a world in which, when approached from a spiritual lens, proffers things both beneficial and satisfying. Our spiritual awareness, far from making us and our world the unappealing undercooked onion puree in the potluck of life, enhances flavor.

I have a friend who was once viewing an article on Mother Theresa. Somehow, the advertisements on the webpage were not set to “Catholic approved,” since, alongside the picture of the now saint, was an ostentatious full screen ad for Plan B. Seriously. It was a perfect example of “what’s wrong with this picture.” Recently, as I was merrily skipping/clicking links that looked interesting, I came to a well-known religious leadership publication. Maybe it was the devil, because he knew it would assuredly annoy me, but the thing my eye caught under the name of the journal was the two words placed next to each other. It looked like this:

I have a friend who was once viewing an article on Mother Theresa. Somehow, the advertisements on the webpage were not set to “Catholic approved,” since, alongside the picture of the now saint, was an ostentatious full screen ad for Plan B. Seriously. It was a perfect example of “what’s wrong with this picture.” Recently, as I was merrily skipping/clicking links that looked interesting, I came to a well-known religious leadership publication. Maybe it was the devil, because he knew it would assuredly annoy me, but the thing my eye caught under the name of the journal was the two words placed next to each other. It looked like this:

GUEST|LIMITED ACCESS

Now, I know this sounds prideful, but as someone who has a handy prime college access, one thing I rarely see when spending time in online journals is “limited access.” Mine isn't limited, it’s full—at least in academic journals. And yet here I was being called a guest, with “limited access.” I was instantly offended. Then I felt guilty about being offended. Here is the thing though, nobody wants to be knowingly excluded to the outer regions of power. This got me to thinking.

I have for a while wondered over the seeming insatiable lust which seems to be incited over positions of leadership. Maybe “lust” is too strong a word; perhaps positions of leadership are more of a thing “craved” than lusted over ... but that would be a hard call. It doesn't matter what setting these leadership positions are in either: be they at a university, church, community, in politics or whatever, the desire to be in a location of leadership seems to be fairly intense. As if to confirm this, more than ever before, I am seeing leadership courses being taught at public libraries, colleges, universities, and even churches. They are popping up everywhere. You can take them in-class, online, or over Skype—whatever method is best for your busy schedule. And such courses fetch good money, too. If you’re worried about your job, don't; you can even get a Masters in Leadership while working full time!

Now, I am not dissing people in positions of authority at all: we need profs and pastors and presidents and prime ministers. Neither am I picking on leadership courses, from what I hear, they bring in much needed funding for places of education. However, I am curious: why the upsurge in interest over leadership? I wonder if the interest is driven by advertisers—like the craze over teeth whitening products. Or is it driven by average Janes or Joes who are suddenly realizing that they would like a title or a position of respect?

Here is the question churning inside my head though: are people becoming more curious about getting into leadership because they feel that it is the primary way they will actually be heard? I.e. that the only way to be listened to, in whatever place they happen to be in, is to be a leader? I realize that there are a few more possibilities than that, but I do wonder if being heard is one of the main reasons.

And if that’s the case, isn't it saying something about our culture? Like, maybe we haven't been willing to pay attention—literally!—to people around us because we assume they don’t have something of worth to say? And if we all think that, then one seemingly reasonable way to get other people to listen to us is not to be an everybody, but a somebody—specifically a leader. After all—leaders have to/must be listened to, right? Again, I am not implying that those in leadership don't have worthy things to say, I just wonder how many times I have contributed to another person not feeling listened to, and thus unwittingly encouraged him or her to seek more formal routes to not only speak, but ensure being heard.

You have probably heard the over-used saw, “tis better to give than to receive.” Now aside from the advertisers who glibly employ it for entirely selfish reasons (may they be sent for a week to the 8th circle of Dante’s hell) here is my annoyance: a gift with a motive is no gift at all, unless it’s to make the receiver thrilled to their booties. Romantic friends with pure intentions know that warming glow felt deep in their hearts as the beloved opens up some carefully chosen little treasure. Parents also know a similar feeling – or so I am told, not yet partaking in parenthood – of watching a twinkly eyed tot ogling over their gifts. I rather doubt that the parents were secretly plotting in the corners of toy department how best to psychologically manipulate their children into being better behaved, or quicker memorise their classical education. If they did, the gift would cease being a gift.

You have probably heard the over-used saw, “tis better to give than to receive.” Now aside from the advertisers who glibly employ it for entirely selfish reasons (may they be sent for a week to the 8th circle of Dante’s hell) here is my annoyance: a gift with a motive is no gift at all, unless it’s to make the receiver thrilled to their booties. Romantic friends with pure intentions know that warming glow felt deep in their hearts as the beloved opens up some carefully chosen little treasure. Parents also know a similar feeling – or so I am told, not yet partaking in parenthood – of watching a twinkly eyed tot ogling over their gifts. I rather doubt that the parents were secretly plotting in the corners of toy department how best to psychologically manipulate their children into being better behaved, or quicker memorise their classical education. If they did, the gift would cease being a gift.

And so, I find myself troubled when one of the greatest Deific gifts offered is seemingly proffered with a large string. Maybe it’s just me, but so often during the holidays I hear, often performed with beautiful voices in song and hymn, that the Christ child has been given to the world as God’s heavenly priceless gift. I feel the tingles now just thinking of it. In the second breath coming from the preacher though, we are told that we owe this divine sovereign something in return. I am bothered.

Sure. I suppose that is the truth. I guess the tot who has just received the gift from pleased parents should feel indebted to her or his familial guardian. (Though, isn't it funny how often the parents look happier than the child!) And yet despite that being the case – maybe – I think if we were to ask the gifting parent whether their child should primarily feel obligation, that parent would suggest that we had never been a parent, or at any rate a true parent. They might even give us a rude look from over a shoulder as they left us standing by the punch bowl.

And so back to the well-meaning religious types who proudly proclaim God’s best gift to humanity ever, ever in one breath, but then in the next espouse how unrighteous we are if we don't hold up to our end of the gift.

Did you see that? The last word shouldn’t have been “gift,” it should have been “deal.” But is that what we humans were given at Christmas, a deal?

G.K Chesterton speaks very fondly of Christmas and of gift giving and goodwill, but also of the nature of the grandest giver of them all. He cleverly uses the name Santa, but all the adults will know exactly of whom he is talking. During the holidays, he says,

[As a child] I hung up at the end of my bed an empty stocking, which in the morning became a full stocking. I had done nothing to produce the things that filled it. I had not worked for them.... I had not even been good— far from it. And the explanation was that a certain being whom people called Santa Claus ... was [a] benevolent agency... [that gave us] toys for nothing. Of course, most people who talk about these things get into a state of some mental confusion by attaching tremendous importance to the name of the entity. We called him Santa Claus, ... but the name of a god is a mere human label. ... [As a child] I only wondered who put the toys in the stocking; now I wonder who put the stocking by the bed, and the bed in the room, and the room in the house, and the house on the planet ... Once I only thanked Santa Claus for a few dolls and crackers, now I thank him for stars and street faces and wine and the great sea. Once I thought it delightful and astonishing to find a present so big that it only went halfway into the stocking. Now I am delighted and astonished every morning to find a present so big that it takes two stockings to hold it.

So why did “Santa” give him the gift of existence? “It was,” says Chesterton, given in “a fit of peculiarly fantastic goodwill.” No strings attached. Except maybe thankfulness.