Review: No Parking at the End Times

Amy Peterson

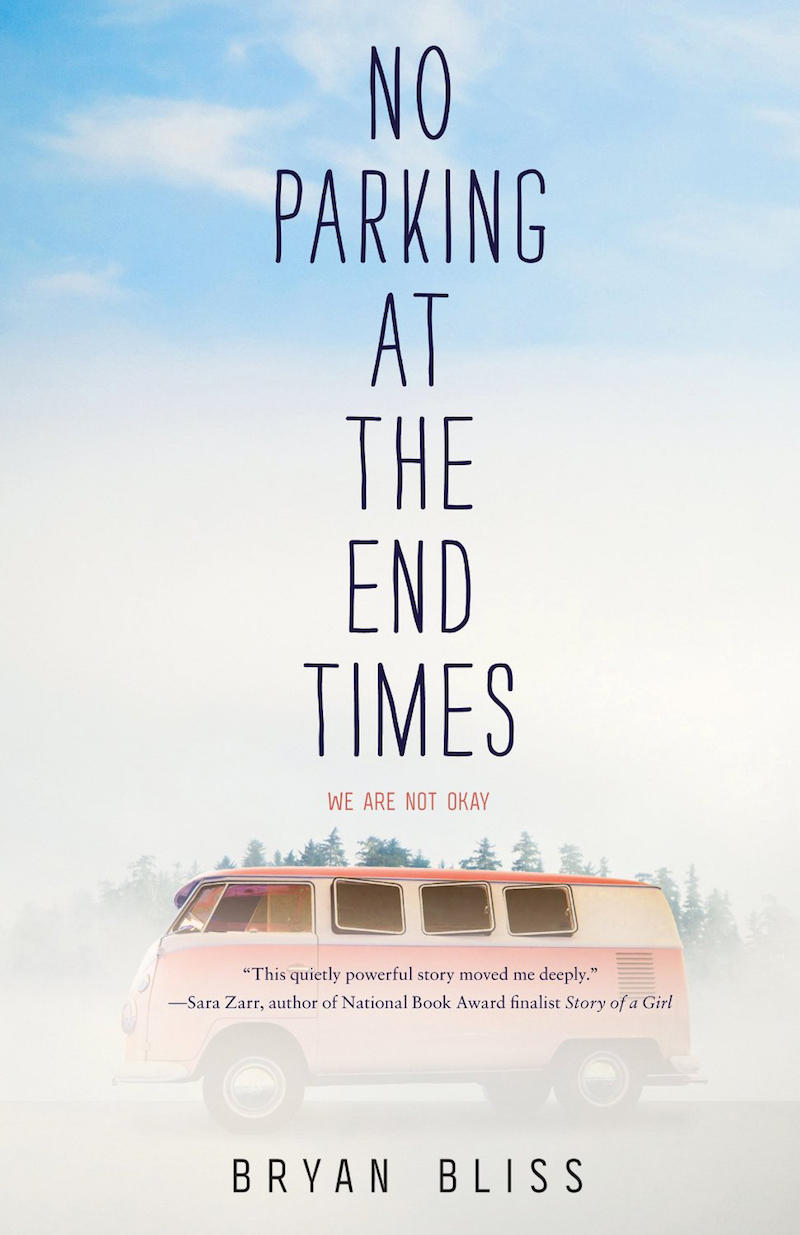

No Parking at the End Times

Bryan Bliss

Greenwillow Books, 2015

No Parking at the End Times

Bryan Bliss

Greenwillow Books, 2015

When do you give up on someone?

In Bryan Bliss’s haunting debut novel No Parking at the End Times, twins Abigail and Aaron don’t agree on an answer to that question.

The book opens in San Francisco, ten minutes before the end of the world, the twins and their parents kneeling in Brother John’s church. Abby, the narrator, prays furiously, half-hoping her faith won’t be in vain, half-hoping it will.

Of course, when the world doesn’t end, Abby’s existence in the realm of childhood innocence ends quite definitively.

Several months before the end of the world, Abby’s family had been happy, lower-middle-class residents of North Carolina. Some time after Abby’s dad lost his job, he began following the radio preacher Brother John, selling off their possessions one by one in order to contribute to the end-times preacher’s “ministry.” Ultimately, they sell their house and move across the country, where they live in their van, praying daily at Brother John’s church. When the world fails to end as predicted, Abby’s dad’s faith is unchanged. Enthralled with the spiritually abusive cult leader, he even sells the van and turns the money over to him.

Though her own faith in God is deeply shaken, Abby refuses to give up on her dad, expecting him to come to his senses and take the family home to North Carolina. But Aaron is certain that they can no longer rely on their parents, and tries to convince Abby that they should leave their parents and take the bus to their uncle. I don’t want to give too much away, but as the twins broker their escape from the cult, they make friends with a group of local homeless kids and become embroiled in new conflicts before finding a way out.

In prose that is spare, certain, and lyrical—an economic style that matches the characters’ environment, no frills to cover the truth—Bliss tells a story of exceptional circumstances with universal relevance. Realistic teenage dialogue and a strong, reliable narrator anchor the story, which covers traditional YA territory (loss of innocence and conflict with parents) while also deftly and sympathetically negotiating larger social themes of homelessness, poverty, and religion.

I didn’t feel sure, as I ended the book, who had been right: was Abby correct to refuse to leave her parents behind, or was Aaron right that they would have to save themselves? I wanted a more conclusive answer. When is it ok to give up on someone—especially someone who has begun to perpetuate a cycle of abuse—spiritual, physical, or otherwise? When does love equal staying, and when must it mean to leave? After all, when your father’s captivity to an abusive cult leader leaves you homeless, shouldn’t you give up on him?

Maybe the closest Bliss comes to suggesting an answer is in The Trumpet Man. A homeless man in Golden Gate Park, the Trumpet Man sings simply, “I am bound!” And being bound means many things. We are bound to our families. We are bound to people who make mistakes, who hurt just as they’ve been hurt. Even the binds that should be cut can’t ever be fully loosed. But we are also bound for a Promised Land, where hurts will be redeemed, unjust inequalities will be set right, and relationships will be restored. No Parking at the End Times points us with hope toward that land.