Editorial Assistant Stephanie S. Smith meditates on the relationship between the Incarnation, the Word made flesh, and the writer, the wordsmith.

I often wonder why, out of all the ways to describe the miracle of God-made-Man, the writer of the gospel of John chose to call it “The Word.”

Editorial Assistant Stephanie S. Smith meditates on the relationship between the Incarnation, the Word made flesh, and the writer, the wordsmith.

I often wonder why, out of all the ways to describe the miracle of God-made-Man, the writer of the gospel of John chose to call it “The Word.”

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” –John 1:1

He says it three times; he really doesn’t want you to miss this: This Jesus? He’s the Word. As a writer who lives and breathes words, this intrigues me.

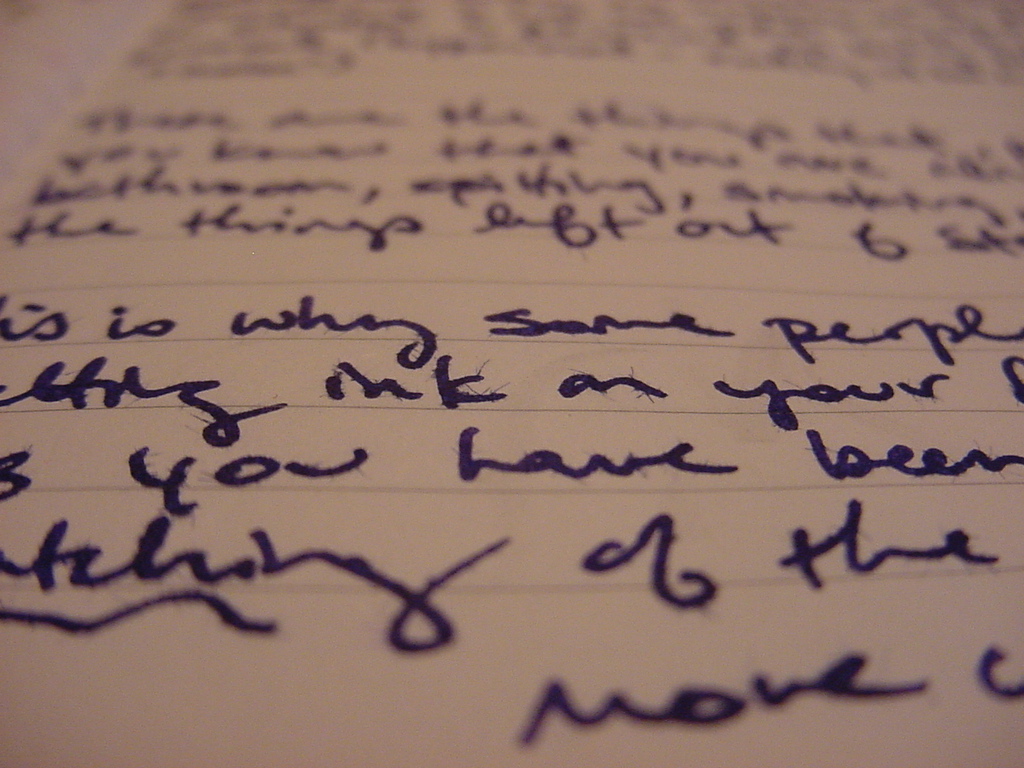

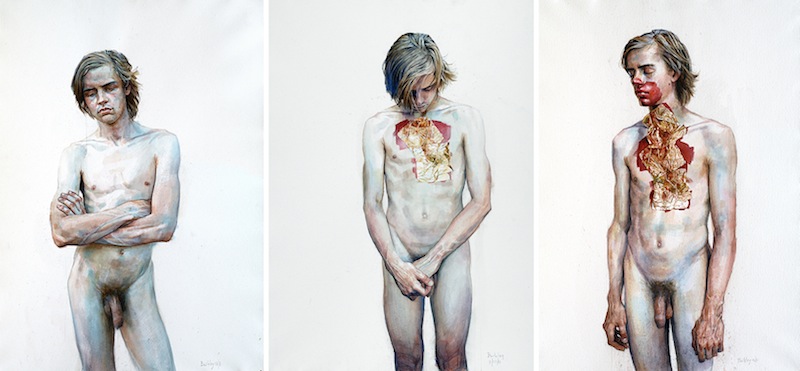

If the Incarnation is composed of the Word given skin, of theology given a body, lungs, hands, sweat glands and elbows, what do my creative words translate into? If the Word became flesh and brought Life to the world, can my words, fragile and human as they are, become something more than ink on a page? Can they also bring life?

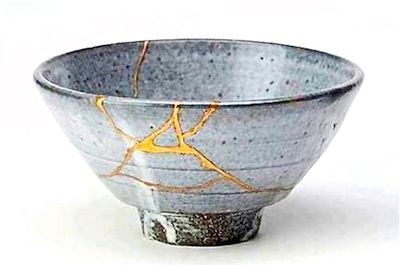

As writers, I believe that our words wield powerful weapons of influence, for better or for worse. And as Christians, I believe we are entrusted with language to point to redemption, by faithfully articulating the brokenness of our world and the wholeness of the gospel. The written word, as creatively communicated in story, poetry, and prose can help us to interpret our lives in light of the greater, eternal context.

Flannery O’Connor affirms this, “The writer operates at a peculiar crossroads where time and place and eternity somehow meet. His problem is to find that location.” Good writing connects the regular details of our lives with eternal reality and puts them on the same plane.

The response of the Christian to the revelation of God should be that of Mary’s, who said to the angel Gabriel, “May it be to me according to your word” (Luke 1:39). Mary, who Scripture describes as a woman in God’s favor, invited the divine word to manifest itself in her very life, which was fulfilled literally in the Incarnation. In the same way, we invite the Incarnation into our lives when we obey God’s Word. We give our faith a face when we love the widow, feed the hungry, visit the sick.

Madeleine L’Engle, in Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, says our writing should reflect the response of Mary, “who, when the angel told her that she was to bear the Messiah, was obedient to the command.” L’Engle remarks, “I believe that each work of art, whether it is a work of great genius or something very small, comes to the artist and says, ‘Here I am. Enflesh me. Give birth to me.’”

In the creative process, the writer-artist responds to each idea like Mary to the angel’s revelation: Yes, manifest yourself in my very flesh, that I may nurture you, cultivate you to grow, and pour you into the world for men to see. The Christian writer uses language as a frame, clothing the abstractness of idea in the flesh of syllables, sentences and words, and then presenting it to the world as a bright and shining advent.

Stephanie S. Smith graduated from Moody Bible Institute with a degree in Communications and Women’s Ministry, which she now puts to work freelancing as a book publicist and writer through her business, (In)dialogue Communications, at www.stephaniessmith.com. After living in Chicago for four years, traveling to Amsterdam for a spell, and then moving back home to Baltimore to plan a wedding, she now lives with her husband in Upstate New York where they make novice attempts at home renovation in their 1930s bungalow. She is a member of the Young Professionals of the Southern Tier and blogs for Moody Publishers at www.insidepages.net.

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement: