Ice Cream Poems

Jayne English

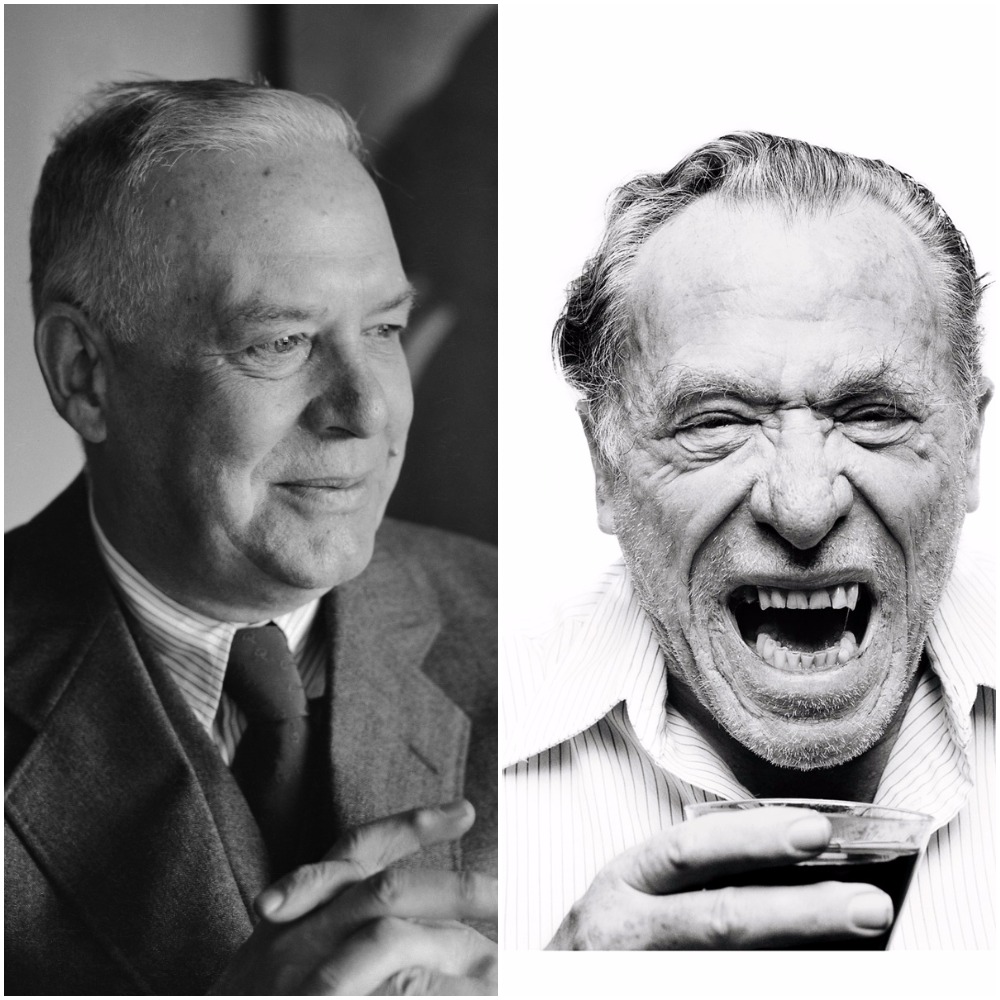

It’s summer, the sky’s a hazy blue and the clouds are piling up like ice cream scoops in a bowl. All motion rendered lazy by the humidity allows my mind to wander. I wonder how many poems there are about ice cream. I know one by Wallace Stevens, “The Emperor of Ice-Cream.” But I stop my languid search as soon as I find Charles Bukowski’s “The Icecream People.” Thinking about the differences between the lives and writing styles of these two poets is as delicious as sampling dulche de leche ice cream and rocky road.

It’s summer, the sky’s a hazy blue and the clouds are piling up like ice cream scoops in a bowl. All motion rendered lazy by the humidity allows my mind to wander. I wonder how many poems there are about ice cream. I know one by Wallace Stevens, “The Emperor of Ice-Cream.” But I stop my languid search as soon as I find Charles Bukowski’s “The Icecream People.” Thinking about the differences between the lives and writing styles of these two poets is as delicious as sampling dulche de leche ice cream and rocky road.

At first, I didn’t see similarities, except that they cohabited the same blue Earth for about 35 years. Wallace was a Modernist poet, breaking with the pre-modern forms of rhyme and the usual subjects of nature and religion to explore ideas about reality being a confluence of imagination and perception. He writes in elegant language with a well-varied vocabulary. Bukowski is also a modern writer who carved a new niche for himself sometimes called “dirty realism.” His poems, short stories, and novels chase a hard, fast line of drinking and women and running riot.

The two poets’ upbringings were very different. Stevens was from a wealthy family and benefitted from his father’s guidance regarding his education and career. Bukowski, who emigrated as a child from Germany to the U.S., was from a poor family. Bukowski’s father’s guidance came on the end of a leather strap that he used to consistently beat him.

Stevens’ education led through Harvard and then New York Law School. He eventually became an insurance executive with The Hartford, and lived a comfortable lifestyle in Connecticut. Bukowski dropped out of Los Angeles City College after two years, and moved to New York to begin a career as a writer. After receiving more rejections than his psyche could tolerate, Bukowski took off across the country on a ten year bender that nearly killed him. Once back in Los Angeles, he began to write again, and began to be published, at first by small publications.

Their book titles alone are interesting contrasts, and give us a vision of at least some of their personality layers. Stevens used elegant titles: Harmonium; Ideas of Order; The Auroras of Autumn. Bukowski’s titles took a different slant: Flower, Fist, and Bestial Wail; Poems Written Before Jumping Out of an 8 Story Window; and Love is a Dog from Hell.

Their language and imagery is wildly different. In the two ice cream poems alone, we come across words and phrases like these in Bukowski: pecker, leper, “nary a potential suicide,” jails, hangovers. In Stevens’ poem we see: concupiscent, “let be be the finale of seem,” “embroidered fantails,” “lamp affix its beam.” Stevens’ thoughts are more abstract, and he dresses them up. As Robert Frost complained, “it purports to make me think.” Bukowski’s ideas are clear, as John William Corrington says, his poetic world is one “in which meditation and analysis have little part.” Bukowski doesn’t dress up his ideas, he strips them naked.

Once his poems are naked, Bukowski speaks of a quasi virility, for example, like this in “The Icecream People”:

the lady has me temporarily off the bottle and now the pecker stands up better.

While Stevens expresses the loss of the same in “Le Monocle de Mon Oncle” like this:

We hang like warty squashes, streaked and rayed, The laughing sky will see the two of us Washed into rinds by rotting winter rains.

While their lifestyles and writing styles are polar opposites, the two men have commonalities. One is a vulnerability to pain. We’ve already seen how Bukowski spent formative years beaten by his father. He said this experience benefitted his writing because through it “he came to understand undeserved pain.” Once on his own, Bukowski lived life running across broken glass—chasing women, gambling, and drinking excessively. Stevens had his miseries too. He married his wife, Elsie, against his father’s wishes. When no one in the family attended his wedding, he never saw or spoke with his father again. In later years, Elsie became mentally ill, showing signs of paranoia about neighbors and the couple’s daughter’s childhood friends. In a review, Helen Vendler calls Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man” his saddest poem, “in which a man realizes that he must make something of a permanently wintry world of ice, snow, evergreens and wind, attempting to see ‘nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.’”

Perhaps it was his sorrow over Elsie that led him into confrontations we’d expect more from Bukowski. Stevens argued on two separate occasions in Key West with Robert Frost (they had strong feelings about their own ideas of poetry), and said things he shouldn’t have said about Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway afterwards started a fist fight over it and Stevens returned home to Connecticut with a puffy eye and broken hand.

Stevens and Bukowski, despite their differences, had another important characteristic in common. They had to write. As one Stevens biography puts it, he saw poetry as “the supreme fusion of the creative imagination and objective reality.” His poem “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” puts it this way:

This endlessly elaborating poem Displays the theory of poetry, As the life of poetry. A more severe,

More harassing master would extemporize Subtler, more urgent proof that the theory Of poetry is the theory of life,

As it is, in the intricate evasions of as, In things seen and unseen, created from nothingness, The heavens, the hells, the worlds, the longed-for lands.

Bukowski talked about the need to write poetry this way:

unless it comes out of your soul like a rocket, unless being still would drive you to madness or suicide or murder, don't do it.

Considering the differences and (maybe) surprising similarities between these two poets, which flavor would refresh your summer day?