Ghost Stories

Scott Robinson

In great deeds, something abides. On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear, but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field to ponder and dream; And lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.

— Bvt. Maj. Gen. Joshua L. Chamberlain

Through a tinted window. That is the most common way to tour the fields of Gettysburg. Whether you hop onto one of the bigger bus tours or opt to follow an audio tour in your own car, you can usually grasp the basics of the historic battle in a few air-conditioned hours. Other than the occasional photo-op at a monument or the perusal of an inscription, the whole affair — although interesting — can feel somewhat pedantic.

Recently I had an opportunity to revisit this battleground from a different perspective. Our little group spent the day marching up hills and across fields, following the Confederate advance through those three fateful summer days. The trip overturned my formerly nonchalant perspective. No longer was I a sunglassed surveyor. In some remote way, I became a participant.

Through the journey, our guide carefully tied each step into the historical narrative. A ridge before us was not just “a ridge that troops crossed”. It was the location in which the 26th North Carolina Regiment broke the lines of the Union’s famed (and previously undefeated) Iron Brigade. The 26th lost 687 of their 843 men that afternoon.

But the stories were more often personal than strategic. Here was the spot where Confederate George Washington Kelly was shot after crossing Willoughby's Run with his regiment’s battle standards. Up ahead was the place (nine flag-bearers later) that Col. John Lane was shot through the mouth while holding those same standards, yet lived to lead another regiment. On a different hill, we stood where 19 year old Union Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson severed the remnants of his leg with his personal knife after being hit by an artillery shell. He died hours later of blood loss.

As we moved along in the gory narrative, I could almost hear the soldiers shouting around me, the mass of grey coats surging forward against the blue. The air seemed to ripple with a silent cacophony of gun blasts. The ground cried out with the blood of brothers. Despite a century and a half of distance, the battle’s oppressive weight was still there, nearly tangible in the afternoon haze.

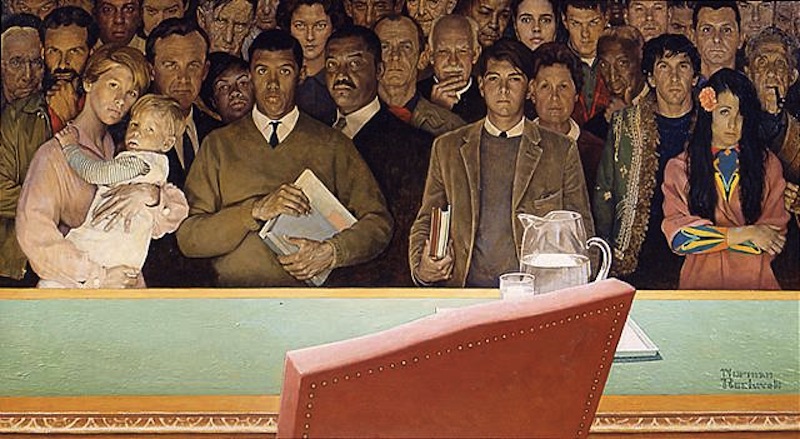

The wraiths within these spaces enveloped me. They left me, not with facts and figures, but with ethereal snapshots: a terrified groan, a rebel yell, a whispered prayer. Data is far more comfortable for me; these ghosts were foreign. A thousand stories strong, they advanced together, filling the empty fields with faces, names, and families.

The echoes of Gettysburg, the poignancies of its moment, are not finally preserved in its maneuvers or numbers — important as those may be. Rather, the heart and soul of Gettysburg is found in its storehouse of narratives, drawn from sonorous tones of old veterans and bloodstained letters pried from cold hands. Through them, Chamberlain’s “shadow of a mighty presence” endures in an amaranthine theater full of tragedy and promise.