When we first arrived, before we entered the silence, we did Lectio Divina together. The words from 1 Peter 3:15 struck me: "In your hearts, set apart Christ as Lord." As we reread and listened to the passage, I kept hearing the phrase, "Christ as Lord." During the third cycle, which asks us to respond to what God is speaking, I prayed, "Christ, be Lord." The prayer moved me toward surrender, and centered me.

Despite that prayer, it took me a long time to be silent inside. The first night, my brain was spinning, my thoughts louder than the silence around me. I spent several hours wandering around the dark, yelling at God. Hope felt as far away as the quiet stars. Eventually I walked inside the dimly lit cathedral, the flap of my sandals reverberating in the emptiness.

I knelt down near the suspended crucifix and began to cry. After hours of wrestling with God, in a moment, the pain behind my anger dissolved into tears. I had the distinct impression that Christ was grieving with me, that I was not alone. I didn't find answers, but I knew God was there. The tears were not only a cathartic release; they became a symbol of surrender.

Silence is a type of surrender. It's a letting go of the incessant spinning within—the worry about what's next, about what I'm not doing, about the people I love, about the people who drive me crazy. Silence requires me to stop whining at God. This is the necessary cessation if one is to inhabit silence fully.

By morning, I felt as if I had accessed a river of peace. I walked around St. Meinrad not so much thinking as being. When people came to mind, I prayed for them, but the prayer felt more like a gentle lifting of them to the Lord than a cognitive exercise. Put in different terms, I felt as if I had accessed the subconscious. A great space broke open in me.

***

Richard Foster says before we can speak or write, we must be silent. We need to be still so we can hear what God is saying to us. Otherwise our words come from a place of noise. I have experienced the truth of this paradox at different points in my spiritual journey as well as in my writing life.

I am a writer. Last year at this time, I could barely choke out those words. It felt audacious, yet I couldn't deny the primal pull words had for me, calling me like the shore calls the sea. I had to respond. A central theme of this past year has been exploring and embracing that identity. I've asked myself, what does it mean to be a writer? A writer of faith? What do I have to say? Why should anyone listen? Does it even matter?

Silence is helping me keep the work I've been called to in perspective. At best, I don't enter silence with an agenda, to have an experience I can write about later. That may happen, but it isn't why I'm silent. I pursue stillness because God has called me to stillness (Psalm 46:10). Stillness not only helps me connect to God, it helps me connect to this work of writing.

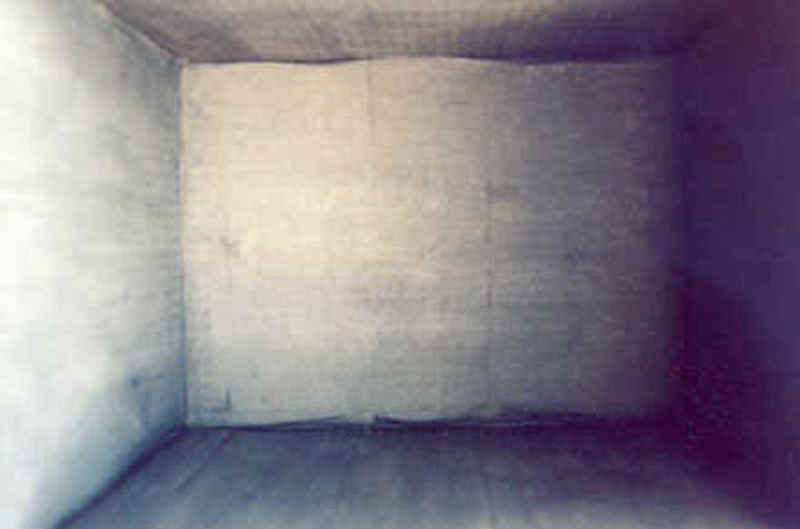

Writing well feels like surrender. I open myself to another place where words flow like water. When I stop striving and am still, sitting in God's presence, I leave space for Him to be God. The same, I'm learning, is true with writing. When I write from a place of rigidity and noise, my words feel stiff, contrived, narrow. When I sit with the white page and let go of my preconceived notions of what's supposed to happen, it works—some of the time, anyway.

Yet stillness isn't a formula that gets me something. Instead it allows me to connect more deeply to myself, to God, and to my work. Some days it feels far away. But the retreat taught me that the river of stillness is closer than I think. I just have to slow down enough to enter it.

Guest blogger Diana Meakem is a senior English creative writing major at Taylor University in Upland, IN. A native of North Carolina, she’s an Ockenga Honors Scholar, member of Sigma Tau Delta, the International English Honors Society, and was the 2014 Editor-in Chief of Parnassus, Taylor’s literary magazine. She has accepted a fellowship at the University of Maine, where she will begin work on her MA in the fall.

(Photo by Hiroshi Sugimoto)