Space for Affection

Christina Lee

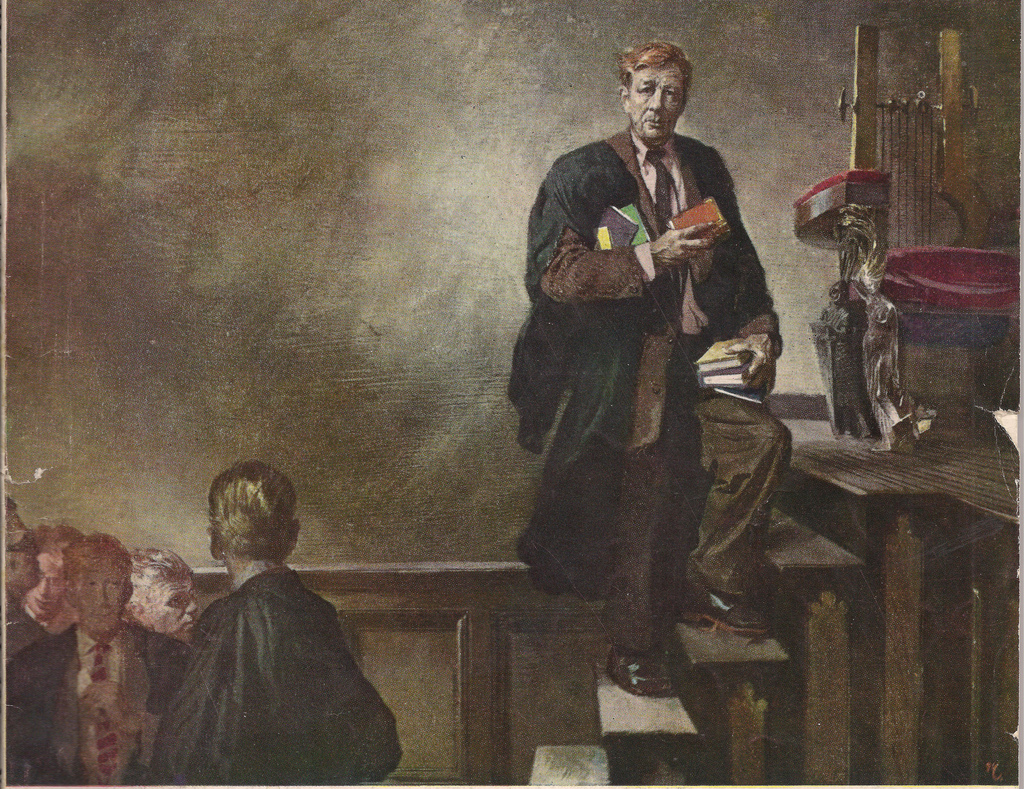

I’m armed with 409 and paper towels, wiping down the desks in my classroom. A few have accumulated clandestine graffiti, the kind made by etching the top layer of wood laminate with the metal tip of a mechanical pencil.

I’m armed with 409 and paper towels, wiping down the desks in my classroom. A few have accumulated clandestine graffiti, the kind made by etching the top layer of wood laminate with the metal tip of a mechanical pencil.

It’s very polite graffiti. So far, I’ve found and excised the following: “I love me.” “Tim is fat.” “The end.” “Andrew + ---” (the name is scratched out).

As I scrub, I remember the students who’ve filled these desks—growing so fast, full of so much, trying their best (usually) to pay attention to my lessons while also trying to make sense of their emotions and their bodies and their world.

(I worry for whoever carved “The End.” It seems so ominous. But who knows? Maybe it’s a ska band.)

Near the back of the room, I find another one: a heart tucked into a desk’s inner edge. This one is deeper, more visible. It must have taken weeks to carve. I know I should be annoyed, but as I wipe out the graphite, I feel an overwhelming sense of affection for my students.

In 2001, Wendell Berry gave an NEA lecture called “It Turns on Affection.” In his own quiet, thoughtful way, Berry wages war on “the industrialization of everything” and on corporations seeking “the highest possible profit, ignoring the side effects,” devastating the land and the farming industry.

Instead of simply seeking profit, he argues, we must cultivate affection for the land and those who farm it. Affection, in his mind, is a powerful tool, one we discount too quickly. “Affection can teach us,” he writes, “if we grant appropriate standing to affection.”

I’m not a farmer (in fact, I’m shocked my grocery-store basil plant has made it through the week), but as a teacher, Berry’s words resonate with me.

My first day back at school, our staff is trained to use a program that promises to produce “data-driven lessons.”

We’re told that after we administer a two-hour, web-based assessment, we’ll be able to generate dozens of reports displaying our students’ deficiencies. Our trainer suggests—straight faced— that if we’re not happy with a student’s performance, we should tell our junior highers, “I just don’t think your data is reflective of your ability.”

As Berry says, “Knowledge without affection leads us astray every time.”

Berry’s lecture calls attention to the great harm done when “people of land economies are reduced to statistical numerals,” and I see the same danger in our schools, which often default to a corporate model, merely dubbing “test scores” over the word “profit.”

Remember “No Child Left Behind,” the law mandating that 100% of students score grade-level-proficient on state tests by 2014—even students with learning disabilities, even non-English-speaking students, even students grappling with severe trauma or family dysfunction? Schools were told that if they didn’t reach that 100% mark, they’d face restructuring and loss of funding.

What a perfect illustration of Berry’s words: “They imagine perhaps nothing at all, their minds being filled to capacity by numbers leading to the bottom line.”

Even after NCLB failed, data is still revered in school settings. It’s universally understood that data finishes conversations, and data definitely trumps affection. Go against this norm and you’ll only embarrass yourself.

It’s right after our data-driven training that I end up cleaning the desks. After I’m done, I sit down to rest in the one marked “The End.” I try to imagine who will fill this seat tomorrow and how that student is feeling about school right now. I try to remember how I felt starting junior high.

"By imagination we recognize with sympathy the fellow members…with whom we share our place," says Berry. "By that local experience we see the need to grant a sort of preemptive sympathy to all the fellow members, the neighbors, with whom we share the world. As imagination enables sympathy, sympathy enables affection."

I know it’s necessary to assess my students’ skill levels. And I know I will work very hard every day this year to ensure that my students reach their data-driven goals.

But to have any real impact on my students’ lives (measurable or otherwise), I must leave space beside the data for “informed, practical, and practiced affection.” As Berry says, “It is by imagination that knowledge is carried to the heart.”

Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”

Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.”

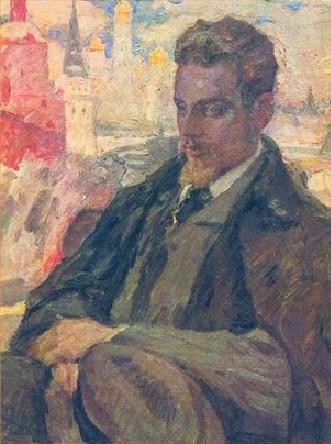

Naomi Shihab Nye describes poetry as “a conversation with the world, a conversation with those words on the page allowing them to speak back to you—a conversation with yourself.” Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his

Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his  I am a trail runner. But when I tell you that, you will get the wrong idea about me. You will picture someone with gleaming calf muscles and a wardrobe stuffed with Lulu Lemon gear.

I am a trail runner. But when I tell you that, you will get the wrong idea about me. You will picture someone with gleaming calf muscles and a wardrobe stuffed with Lulu Lemon gear.