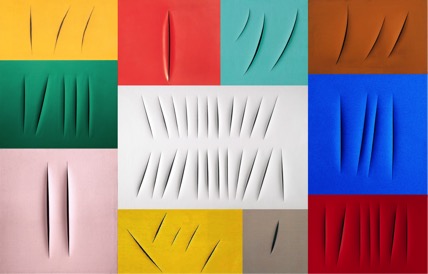

Spatial Concepts

Lou Kaloger

In the late 1940s, Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) took a knife and slashed a canvas that had been painted in a solid color. He called the piece Spatial Concept. Over the next two decades, Fontana produced a large number of similarly-slashed and similarly-titled works in a wide variety of sizes and colors. One of his last pieces was produced in 1964. It was white and contained twenty-three slashes. In February of this year, it sold for over $12.4 million.

Fontana's work was not without forethought and purpose. By relieving the canvas of its tautness, he sought to smudge the lines between two- and three-dimensional art and grant the surface a distinctively sculptural quality. In this sense, his Spatial Concepts seemed to stand as a protest against traditional art, particularly the work of Flemish still-life artists. After all, the depth, texture, light, and perspective of a Flemish still life is artificial. It is an illusion created by fooling the eye through technique.

The space depicted in Fontana's work can be measured. The space depicted in a Flemish still life is just a story.

Or so it seems.

Fontana's slashed canvases may have been "accurate," but the stories told by these Flemish still lifes said infinitely more. Many were chronicles of an individual's life summed up in the artifacts he or she owned. The best of them almost always included a memento mori. These "mementos of our morality" might be presented in the form of a bleached skull, a diminishing hourglass, a half-eaten apple, or an extinguished candle. Each served as a vivid reminder that the story of life is told best when we remember that we are but a vapor called to abide in the One who is from the beginning.

I guess that's the power of all good stories: Sentences with nouns and verbs. Rich imagery and tumbling metaphors. Stories about people, and places, and circumstances. People different from us, but also people a lot like us. Good stories measure.

Will I find myself in that story?