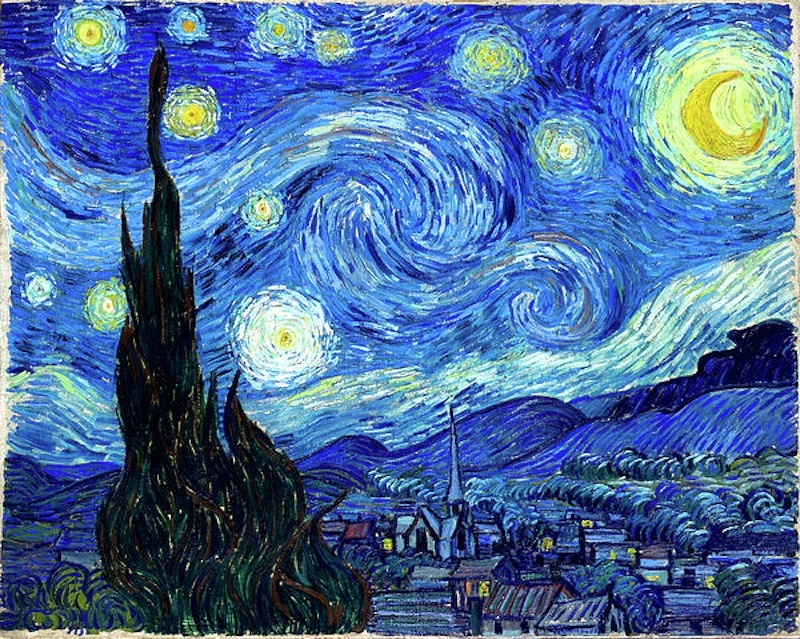

Van Gogh and Victor Hugo Meet “in the center of the starry night”

David Kirkpatrick

“I dream of painting and then I paint my dream,” Vincent van Gogh reportedly said. In the case of his most famous painting, The Starry Night, he may not have dreamed it, but may have found it in the words of Victor Hugo. Victor Hugo and Vincent van Gogh never met in person. However, an avid reader of fiction, Van Gogh was extremely moved by a passage in Hugo‘s masterwork, Les Miserables. This is, according to William J. Havlicek, Ph.D., author of the marvelous Van Gogh's Untold Journey, the passage from Les Miserables which inspired Van Gogh:

“I dream of painting and then I paint my dream,” Vincent van Gogh reportedly said. In the case of his most famous painting, The Starry Night, he may not have dreamed it, but may have found it in the words of Victor Hugo. Victor Hugo and Vincent van Gogh never met in person. However, an avid reader of fiction, Van Gogh was extremely moved by a passage in Hugo‘s masterwork, Les Miserables. This is, according to William J. Havlicek, Ph.D., author of the marvelous Van Gogh's Untold Journey, the passage from Les Miserables which inspired Van Gogh:

“He was out there alone with himself, composed, tranquil, adoring, comparing the serenity of his heart to the serenity of the skies, moved in the darkness by the visible splendors of the constellations and the invisible splendor of God, opening his soul to the thoughts that fall from the Unknown. In such moments, offering up his heart as the flowers of night emit their perfume, he lit like a lamp in the center of the starry night, expanding in ecstasy the midst of creation’s universal radiance, perhaps he could not have told what was happening in his own mind; he felt something floating away from him, and something descending upon him, mysterious exchanges of the soul with the universe.”

We often think of Vincent van Gogh as a nut job: a reckless artist who cuts off his ear as a gift to his lover, a man in so much pain he offs himself. If we take the time to actually glimpse the pentimento beneath the true portrait of van Gogh, we might find a very different painting. This portrait might show the artist as an avid reader, a thoughtful writer (writing over 1000 letters in his brief lifetime), an artist devoted to evoking the divine in his work, and a follower of Jesus.

In a Letter to Emil Bernard on June 26,1988 van Gogh wrote,

“Christ lived serenely, as an artist greater than all other artists, scorning marble and clay and paint, working in the living flesh. In other words, this peerless artist, scarcely conceivable with the blunt instrument of our modern, nervous and obtuse brains, made neither statues nor paintings nor books. He maintained in no uncertain terms that he made…living men, immortals.”

This letter was written a year before van Gogh checked into the asylum in Saint-Remy France. He moved into the asylum for sleep disorders and fits. The latest information points to van Gogh suffering from chronic sleeplessness due to a combination of genetic epilepsy and brain damage from absinthe abuse. New information gathered from Pulitzer Prize winners, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, indicates that Van Gogh did not commit suicide, but that he was killed by some local town ruffians when a gun malfunctioned. In a pointed assumption by the writers, they believe because of van Gogh’s “Christian nature,” he kept the incident from the authorities. It took several days for the artist to die, and while he was dying Van Gogh told the authorities that the wound was self inflicted (he was terribly sick anyway). The theory is that he did not want the accident to destroy the young lives of his assaulters.

As a culture, we are fortunate that Hugo and van Gogh met not in real time, but “in the center of the starry night”. For without Hugo’s writing, van Gogh may never have been inspired in the way that he was to paint what has become one of the most beloved and recognized paintings of the modern epoch.

(Painting by Vncent van Gogh)