Email From a Young Poet

Howard Schaap

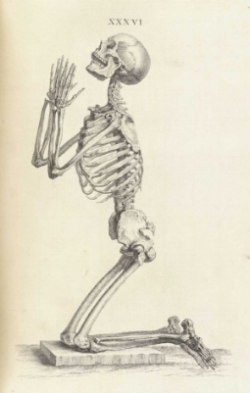

Osteographia, or The anatomy of the bones. Cheselden, William, 1688-1752.

“I like the poem ‘Purity’ by Billy Collins as a way to think about writing poetry,” a poetry student wrote to me recently. She also had some profound questions about the poem, beginning with, “As Christians, while writing poetry, are we still Christians after we’ve stripped ourselves pure as Billy Collins says?”

As a teacher, this is the kind of question that makes me pinch myself and say, “They pay me to do this.”

First, the poem.

“My favourite time to write is in the late afternoon,” writes Billy Collins in “Purity,”

weekdays, particularly Wednesdays.

This is how I got about it:

I take a fresh pot of tea into my study and close the door.

Then I remove my clothes and leave them in a pile

as if I had melted to death and my legacy consisted of only

a white shirt, a pair of pants and a pot of cold tea.

Knowing Collins, one can pick up the irony in his voice early—if not at “Purity” itself, then at “particularly Wednesdays,” that day of woe. When he takes off his clothes the jig is up completely, and at the melted death we might very well be LOLing.

Collins has identified “purity” by the end of stanza one as the pesky fly of temptation that it is. But he doesn’t stop there. The larger point and funnier comedy is still to come. Stripped down naked, we’re left with the body and what could be less pure than that? He continues,

Then I remove my flesh and hang it over a chair.

I slide if off my bones like a silken garment.

I do this so that what I write will be pure,

completely rinsed of the carnal,

uncontaminated by the preoccupations of the body.

Lest we miss the sarcasm—why would we want to write or read poetry “rinsed of the carnal?”—Collins doubles back on himself to emphasize just how impossible it is to get outside of something like “manhood,” one’s manliness, one’s junk.

I should mention that sometimes I leave my penis on.

I find it difficult to ignore the temptation.

Then I am a skeleton with a penis at a typewriter.

In this condition I write extraordinary love poems,

most of them exploiting the connection between sex and death.

But hold the phone. Is there a sort of double irony here? We’re not just limited in writing to our pervy sexual selves, are we? Is the irony of the poem the fact that we can’t get out of our bodies? Or is the irony that we’re no longer allowed to—that everything must come down to the driver’s license measurements of who we are?

Remember the original question: where does self end and faith begin? Here’s my student again: “Our deepest and truest selves are found in Christ. But at the same time, I feel like to be honest about our human-ness, we need to write about how we (or others if writing in 3rd person) don’t always remember this?”

What do we do with the imagination if we can’t send it out—purely, ideally—to inhabit another body, to imagine its way into another time, place, existence, reality?

And isn’t one of the goals of supposedly honest writing to confront our innermost selves as human beings, no matter what we find there? (“The horror! The horror!”) The layers that Flannery O’Connor reveals in the Grandmother in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” come to mind.

Maybe the answer to both these questions is the same: “Yes, but. . .” Maybe the answer is just, It’s a frightening thing, this writing.

Or maybe through laughter Collins’ poem attempts to free us from fear—both the fears of going out, and those of going in—by freeing us from the idol of “purity.” Neither effort will ever be “pure,” and if we set those ideals aside, maybe it just frees us to do good, bodily work.

Still, I can’t help but think this student’s question is the perfect one for Christian writers—or for writers who are Christians—or whatever “leap then into the arms of God” kind of state a person who happens to write finds him/her/cis/trans self in. There is a temptation to try write beyond faith to the true self. I can’t help but think this is the central idol of a certain kind of writing, and an idol I am certainly tempted by—to write to a truer truth about the self than the simple sap in the pew understands.

But that just means you’re writing into another kind of faith, not beyond it. You can’t write beyond faith, I told this student. You can find you haven’t clothed yourself in Christ the way you should have, that you have other clothes on altogether, or are naked. But that’s a good thing—though not a fun thing—to find out.

It just means you once again try to put on different clothes, to put on Christ.

And then sometimes, despite all your prattling, you find yourself saying something surprisingly faithful, though it might not sound like the language of faith. Like Flannery’s Grandmother, you just look into the image of God in the Misfit before you and say something like, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children."