Billy Collins’ poem “Aimless Love” strikes a special chord with me. The poem, wherein Mr. Collins falls in love with “... a wren/ and later in the day with a mouse/ the cat had dropped under the dining room table,” makes me remember my first love. I was only a child, and it was a brief affair — a deep, fleeting affection that was not reciprocated — but which set the tone for many of my experiences as an adult. My first love, you see, was an ant on a clover in my neighbor’s yard.

Billy Collins’ poem “Aimless Love” strikes a special chord with me. The poem, wherein Mr. Collins falls in love with “... a wren/ and later in the day with a mouse/ the cat had dropped under the dining room table,” makes me remember my first love. I was only a child, and it was a brief affair — a deep, fleeting affection that was not reciprocated — but which set the tone for many of my experiences as an adult. My first love, you see, was an ant on a clover in my neighbor’s yard.

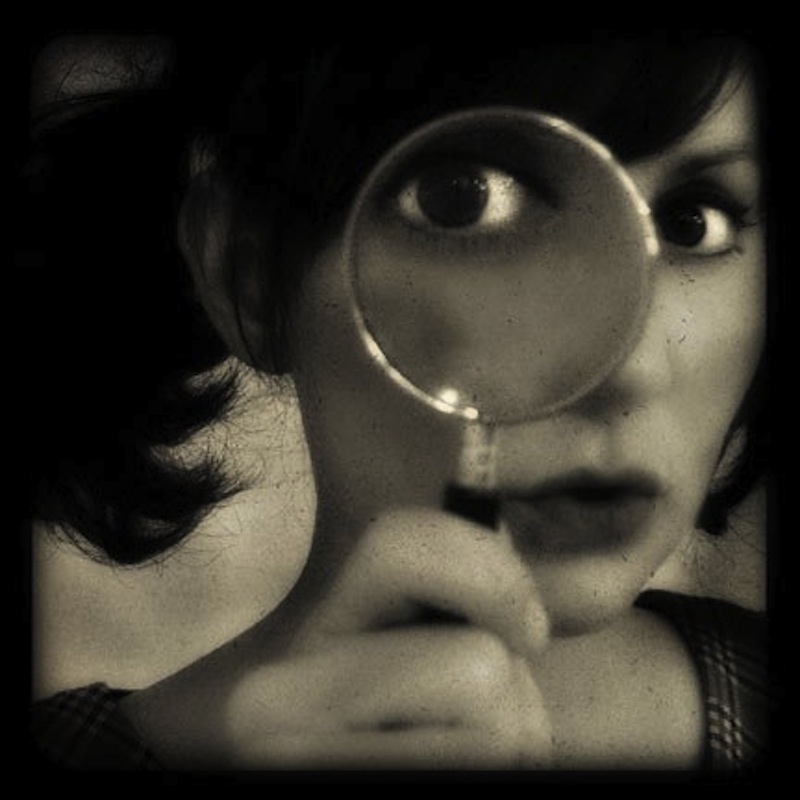

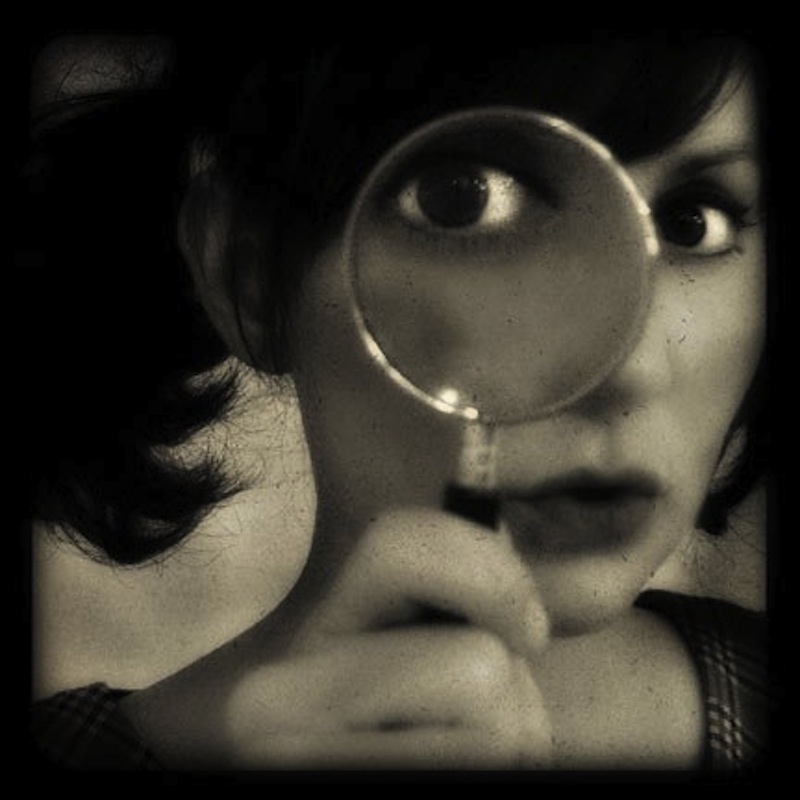

My sister and I decided to “go on a safari” outside. So we packed a backpack with some paper, a magnifying glass, and several apples, and solemnly announced to our mother that we were Going Outside to Be In Nature. Off we went, and, through some series of events, I ended up face down in a neighbor’s yard watching an ant on a clover. As I watched it climb, I felt a sudden deep, fierce love for that bug. It was so small, and the flower it climbed was so much larger than it was, and the grass in the yard towered over it like a forest, and I was keenly aware of how large in the world I was, and how clumsy, and how apt I was to overlook small things like ants on clovers.

Such love seems very human. I always tend to roll my eyes when people throw around the phrase “God is love.” It makes me think of awful little Victorian cherubs and vacuous worship songs. I’ve always thought of God more in the Old Testament sense — the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob who spoke light out of the darkness, who stopped the sun in the sky while his people fought at Gibeon. God is love, of course, but I have always thought of God’s love in a more terrible, cosmic kind of way, not the kind that’s fussed by everyday details. That’s why the passage wherein God is described as knowing when a sparrow dies always startles me — it’s hard for me to imagine. But it is a beautiful thing to know that God does know when a sparrow dies, or that he cares even for the lilies in the valley, or that he can count the number of hairs on my head.

That ant was a long time ago. But I am now very familiar with that sudden, painfully clear love for small things. Like Collins, who falls in love with steam rising from a bowl of broth, whose heart is “always propped up/ in a field on its tripod/ ready for the next arrow,” I direct my affections at odd, unsuspecting people or objects — my friend’s face, illuminated as she bends over the stove; the shape of my cat on a chair; a particular shade of green. It’s a fleeting, aimless love. But I do like to think that, maybe, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is looking with me and loving the details. Even the ants on clovers.