A Shimmering Mass

Aubrey Allison

"Thus, writing narrative—and reading it—is an act of faith that places us in time and space, locating us in a chronology that suggests by its very order both the cause and meaning of our lives." —Leslie Leyland Fields in Christianity Today.

"Thus, writing narrative—and reading it—is an act of faith that places us in time and space, locating us in a chronology that suggests by its very order both the cause and meaning of our lives." —Leslie Leyland Fields in Christianity Today.

*****

Lubomyr Melnyk has spent his life pioneering a new kind of music for piano: continuous music. "The basic concept," he says, "is that it's a continuous stream of sound, unbroken. There are no phrases of slow notes, rapid notes, and pauses, the way other music is built.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbzU7MT-lHU

Listening to continuous music takes some getting used to. (This is especially so when you hear the music live. The sounds move through a room and bounce off walls differently than they do in a recording.) It requires a kind of attention that I, at least, had to cultivate, not unlike meditation. Melnyk himself has spent decades cultivating these skills: he’s trained his hands to play almost twenty notes per hand per second, and some of his pieces last forty-five unbroken minutes or longer. The effect is fundamentally different than classical and other conventional forms of music. It’s music to get lost in—you must get lost in it in order to follow it.

Continuous music is not built around the traditional structure of melody; rather, it is a sonic space Melnyk creates in which the sound of the piano itself flourishes. Notes build upon and interact with one another in a way that is fluid and almost out of control, almost like chaos. Once you get used to this, classical piano compositions start to feel stiff and incomplete in contrast. Melnyk compares himself this way: "Classical pianists, they live in the music they're playing. They live in the sonata; they live in the piano concerto. They don't live in their fingers."

Continuous music fascinates me in part because it seems like an antidote to an over-emphasis on story. I’m suspicious of story, of the popular push to understand our lives as part of a larger narrative. God’s narrative. In part, story is an alternative to the conception of Truth as propositional—laws, dogma, rational systems, assertions to be proved or disproved. When Christians understand their faith as participation in a divine story, Truth can operate in many different ways—experienced, incarnated in individual lives, unspeakably complex.

But I suspect that the idea of life in a narrative structure—even if it’s a structured unknowing—is shaping my expectations in a way that stops me from being entirely present. I wonder if, when I imagine my confusions, pains, encounters, and observations as material to one day be grasped and threaded together into a coherent arc—I wonder if I’m stopping short of a threshold where life is more unwieldy, but also deeper and more luminous.

When he plays, Melnyk keeps his foot on the sustain pedal, lifting the dampers away from the strings, allowing them to vibrate freely and the notes to decay naturally. With the dampers lifted, surrounding piano strings can also vibrate in sympathy with strings whose vibrations are mathematically related to their own, meaning that many strings vibrate without being struck. New patterns emerge from their interactions. At times, it’s difficult to tell if their swells are real or imagined.

When I live in anticipation of divine narrative in my own life, I suspect I’m living in the sonata, in the concerto.

I want to know what it’s like to live in my fingers.

Instead of a melody, a progression of notes, the notes in Melnyk's music are a shimmering mass, accumulating and undulating through the space around him. When you are in a room with Melnyk playing piano, you are in a room where sounds and harmonic relationships are bouncing through the space and compounding one another, creating swells and ripples in the air. There is Melnyk, alive in his fingers, and there is the music, continually escaping structure, continually expanding.

What else is there to do but listen?

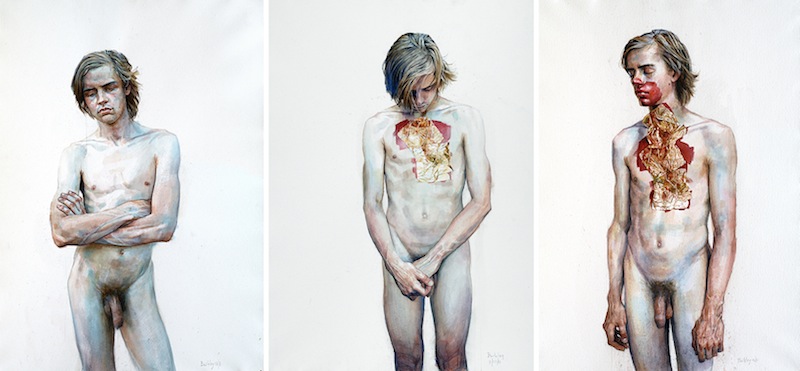

Paintings above by Alex Kanevsky