“... the only way of ‘mastering’ one’s material is to abandon the whole conception of

mastery and to co-operate with it in love: whosoever will be a lord of life,

let him be its servant. If he tries to wrest life out of its true nature, it will revenge itself

in judgment, as the work revenges itself on the domineering artist.”

(Dorothy Sayers, The Mind of the Maker, 186)

In The Mind of the Maker, Dorothy Sayers makes the intriguing point that our modern culture typically approaches life according to a scientific or analytic “problem and solution” paradigm rather than what she calls a “creative” paradigm. As she states, modern man views life “as a series of problems … which he has to solve with the means at his disposal. And he is distressed to find that the more means he can dispose of — such as machine power, rapid transport, and general civilized amenities, the more his problems grow in hardness and complexity. This is particularly disconcerting to him, because he has been frequently told that the increase of scientific knowledge would give him ‘mastery over nature’ — which ought surely to imply mastery over life” (185-6). In short, we try to take a method that’s applicable to a small subset of human experience and try to apply it to all areas of life, indeed to human life itself.

In her creative paradigm, life isn’t a problem to be solved, nor the mystery of the universe an equation to be worked out; for one thing, these imply the ability to master life. Rather, in this view (as Christine Fletcher summarizes Sayers), “life presents a series of opportunities to make something new” (The Artist and the Trinity, 96). The artist, for Sayers, doesn’t stand outside life as an engineer, but, open-endedly, within life, working with the elements of life according to their nature, in order to make something out of them in harmony with their nature, essentially in an ongoing process of being fruitful and multiplying, that is, in all the various aspects of human life and human interaction with the world. Sayers applies this creative paradigm not just to the artist in the narrower sense, but to the fabric of human nature itself, indeed suggesting that “creative mind is … the very grain of the spiritual universe” (Mind of the Maker, 185).

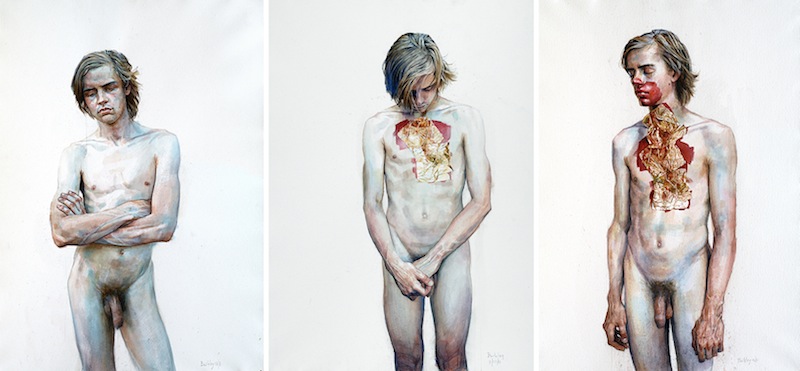

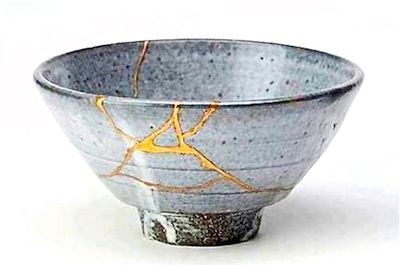

Thus, central to what Sayers is arguing seems to be that modern man does not want to live life (this ongoing fruitful process); he wants to master life. Modern man seeks to overcome even the deeper problems of life through, e.g., analytic or machine techniques, seeking to conform the world to human will. But the creative paradigm doesn’t seek to master nature. It works with the materials received, according to their nature, to bring forth yet new things. Therein, even “the pains and sorrows of this troublesome world can never … be wholly meaningless and useless.” The artist will seek to “make something of them” (192-3). In short, they are the materials for a new creation or a new synthesis. This, Sayers argues, is the pattern that Christian theology provides as well. And there is a striking parallel, e.g., in the Incarnation. The problem of the Fall isn’t simply “solved” in the sense that problematic elements simply disappear by force of will and reason. They become themselves part of the very elements out of which something brand new is brought forth. God enters within the context of human life as things stand and creatively engages with all the factors involved according to their nature (taking on the “likeness of sinful flesh” [Rom 8:3]). Thus all the materials of the fallen order are employed to create something new. To be sure, God “adds” new materials — the supernatural breaking into the natural — but the old materials are integrated into the new, having been transformed into something glorious through God’s creative work. One is reminded of C. S. Lewis’ analogy, in “The Grand Miracle,” of discovering the missing, central passage of a symphony or chapter of a novel, which, when plugged in, transforms and transvalues its whole meaning, making new sense of all the other parts, forming a masterpiece. Thus, though life is often, in large part, made up of tragedy we can rest in God’s promise and his creative power that he can take all of those elements — the scars, pain, loss, and all other seemingly useless material — not simply erasing them or resetting everything to zero, but creatively forming out of them a new creation of unforeseen glory (how else could a crucifixion be the creative means of glorifying the Son of God?).

Do we perhaps often stand “outside” life, seeking to engineer our lives and thereby gain mastery over it through techniques, or (similarly) get lost in imaginary scenarios that could have been but are not? If Sayers is correct, should we not rather stand “within” life, as its servant, imaginatively interacting with what is there, engaging with life in media res, seeking to create new forms and re-integrations of the good, the beautiful, the true (in all walks of life)? While also, of course, admitting to the tragedy and the brokenness and the longing of life that cannot be assuaged by human ingenuity.

(Painting by Frida Kahlo)

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever

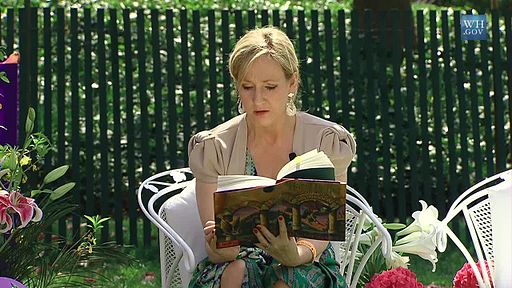

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever  I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

“But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, but can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty in it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties.”

― Kenneth Grahame,

“But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, but can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty in it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties.”

― Kenneth Grahame,  Read Part I

Read Part I