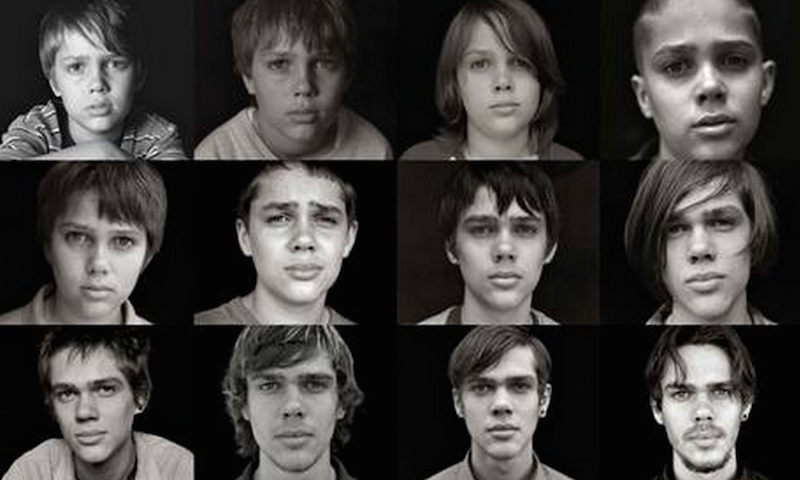

Boyhood, Birdman and the Problem of Existence, Part 1

Drew Trotter

Birdman and Boyhood shared more than the race for the Best Picture Oscar last year. Though the two movies were as different as can be imagined in tone, form, subject matter, pace, and just about every other movie-making category, they were unified in pushing to the forefront a philosophy that goes back some fifty years, but seems to be gaining momentum as a philosophy of life: existentialism.

Birdman and Boyhood shared more than the race for the Best Picture Oscar last year. Though the two movies were as different as can be imagined in tone, form, subject matter, pace, and just about every other movie-making category, they were unified in pushing to the forefront a philosophy that goes back some fifty years, but seems to be gaining momentum as a philosophy of life: existentialism.

Existentialism is known best at the popular level as the theory that the only meaning one can find in life is by living authentically, i.e. passionately and sincerely, in the moment. The “now,” not the “then” on either side of it on the timeline of existence, is the only part of reality that is relevant, and an existentialist is responsible for creating meaning in that “now.” That meaning, however, does not transcend the “now,” but rather requires the doer to live in a series of disconnected moments as authentically as possible to achieve significance. All of this is predicated on the universe being meaningless, there being no God, and therefore no revelation of where meaning for the human being is to be found.

The conversation that shows how serious Boyhood is about its existentialism comprises the last scene in the film. Mason, Boyhood’s main character, is on a hike on his first day of university. He has typically skipped orientation and has met a new girl, Nicole; they are hitting it off. At a beautiful moment of sunset with the rocks glowing that soft red they do in the Texas desert, Mason and Nicole are sitting together, enjoying a brief rest, awkwardly trying to continue the conversation they’ve been having during the walk. Suddenly Mason’s roommate, a crazy extrovert, yells out from down below: “This moment’s having a falsieful whoregasm! It’s like as if all of time has unfolded before us so we could stand here and look out and scream, ‘Fuck yeah!’ Wooo!”

This juvenile moment prompts the much more thoughtful, yet still feeling-her-way Nicole to turn to Mason tentatively and volunteer, “You know how everyone is always saying, ‘Seize the moment!’? I don’t know. I’m kinda thinkin’ it’s the other way around, you know, like, the moment seizes us.” Mason responds, “Yeah. Yeah, I know. It’s constant. The moments. It’s just, it’s like it’s always right now, you know?” She agrees. They look at each other, again in only that way two young people can, who aren’t sure of the future, but are thinking, “I really like this girl/guy; do you think he/she is the one?” They look away, then look back, and the movie cuts to black, ending.

As if this weren’t enough, as the credits roll, a lone voice begins singing, “Here, at my place in time, and here in my own skin, I can finally begin. Let the century pass me by. Standing under my sky, tomorrow is nothin’.”

One couldn’t find in modern film a more existentialist way of viewing life. “It’s like always right now, you know?” But Boyhood cheats because it ends hopefully. The viewer feels Mason has his whole life ahead of him and sees it as an adventure, filled with moments, some of joy, some of sadness, some of reward, some of punishment, but all to be embraced and simply lived until the next one comes. Classic existentialists, on the other hand, could not get over the loss they felt at the knowledge that we create our own meaning in every moment. It made life absurd, random, without any ultimate significance. This newer popular form of the philosophy simply chooses to ignore the consequences of the future, particularly the looming specter that so terrified Sartre, Camus, Becket and others: death.

That specter dominates, in some ways, the other movie, the one which won the big prize: Birdman. Stay tuned.