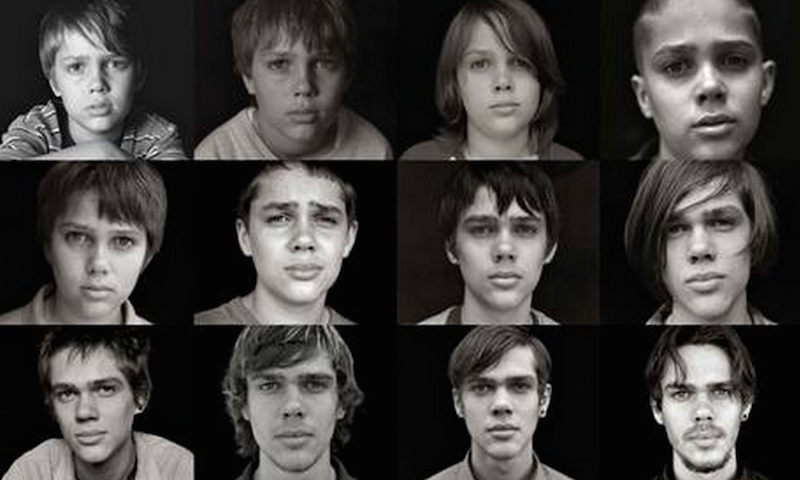

Boyhood, Birdman and the Problem of Existence, Part 3

Drew Trotter

In my last two blog posts, I have tried to show how both Boyhood and Birdman seem bent on resurrecting a philosophy popular in the 1960’s: existentialism. While Boyhood seems to give a hopeful spin to its form of it, Birdman presents a much darker picture, linking existentialism to what was commonly thought then was the only truly authentic act in the face of the death of God: suicide. Albert Camus fought this notion, but many under the influence particularly of Friedrich Nietzsche, embraced it thoroughly.

In my last two blog posts, I have tried to show how both Boyhood and Birdman seem bent on resurrecting a philosophy popular in the 1960’s: existentialism. While Boyhood seems to give a hopeful spin to its form of it, Birdman presents a much darker picture, linking existentialism to what was commonly thought then was the only truly authentic act in the face of the death of God: suicide. Albert Camus fought this notion, but many under the influence particularly of Friedrich Nietzsche, embraced it thoroughly.

Now, I am a Christian theologian, and I believe that Christianity spends a lot of energy encouraging us to realize that the present is the only moment we have in which to act responsibly. We share this in common with existentialism, this focus on the present in the journey of our own lives. We can do nothing about the past because we cannot alter it, and we can do nothing about the future because we do not know what challenges it will bring. Therefore, following the Good Shepherd in the moment is what we are called to do, and it is enough.

One does not have to look far in Christian teaching for support for this way of living. I think of Jesus’s statement in the Sermon on the Mount about not being anxious for anything: “Therefore do not be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.” (Mt 6.34 ESV) or the ancient wisdom of Prov. 27.1: “Do not boast about tomorrow, for you do not know what a day may bring.” (ESV).

These two statements are about the future, but, similarly, the regrettable past is forgiven and forgotten in a very real sense for the Christian, and, while the memories of works of beauty and goodness that may have been done to us or by us, are great gifts, we cannot change those gifts, nor would we want to.

But—and it is a very large “but” indeed—all our understanding of both the past and the future takes place in a universe in which God oversees the past, the present and the future from His eternal stance outside of time. He bestows meaning to our existential moments in the framework of both an ethical structure based in the law, which in turn is based on His eternal character, and a metaphysical structure based in His revelation of Himself as creator, redeemer, and sustainer. All meaning flows from Him, and provides us a rich and satisfying philosophy by which to live and in which to believe. He gives meaning to both the past and the future, and so we, His creatures, can rest assured about both the reality of, and the significance of, both the past and the future. We may not be able to change them, but we look at them with very different perspectives than do the existentialists.

I do not see any alternative better than this. Camus’s notion of revolt in the face of the absurdism of a universe without God is purely a decision to go in a direction he wants to go. His attempt in “The Myth of Sisyphus” to answer in the negative the question of whether or not one should commit suicide in the face of an absurd universe is unconvincing. Even worse is his attempt ultimately to justify the embrace—happy embrace, I might add—of the fate of pushing the rock to the top of the mountain each day, only to see it roll back down to the bottom every night. He simply gives us no reason to feel that this is a better alternative than simply to end it all in despair.

But the greatest fault of existentialism is its premise that God does not exist. The much better hypothesis is that He does, and that He has revealed Himself in Christ for the good of the world. The hope of Boyhood is not wrong; it’s just misplaced given its premise. The craving for love in Birdman is not wrong; it’s just misdirected from looking for God’s approval to looking for man’s (John 2:23-25). The Christian can hope and can love because of their faith, the faith that the one true God exists and gives life and meaning to the past, the present and the future.