Aaron Guest

There were only a handful of parents at our daughter’s ballet recital. We were all dressed in jeans and jackets and shoes, our phones recording, sitting in the corner of the YMCA studio, our backs to the full-length mirrors. After the recital had begun, one mother began crawling across the wood floor, from one end of the studio to the other. Her scramble immediately struck me as unnecessary and annoying. Get up and walk.

There were only a handful of parents at our daughter’s ballet recital. We were all dressed in jeans and jackets and shoes, our phones recording, sitting in the corner of the YMCA studio, our backs to the full-length mirrors. After the recital had begun, one mother began crawling across the wood floor, from one end of the studio to the other. Her scramble immediately struck me as unnecessary and annoying. Get up and walk.

“What kinds of reality are considered prerequisites for compassion?” Leslie Jamison asks in one essay in her excellent collection The Empathy Exams. How dissimilar does a person’s life have to be before we fail to show them compassion? Jamison’s essays present us with people who believe they have worms emerging from the their skin, who drive themselves insane in highly competitive adventure races, who have abortions. When the realities grow farther apart from our own, it’s likely the capacity for compassion shrinks, she suggests.

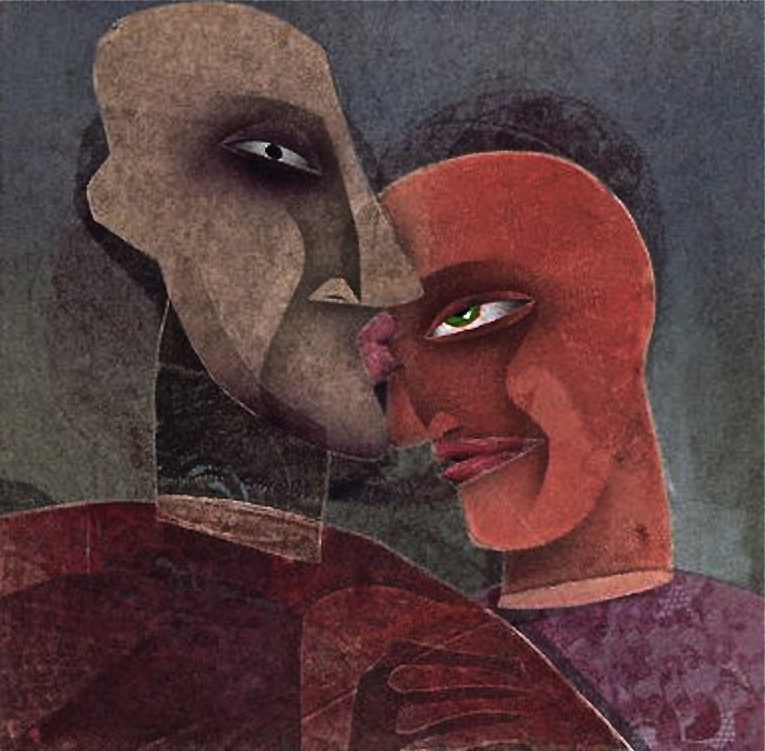

But being a writer, I’m willing to wonder about others who inhabit a different reality. I relish this getting up and going outside of my own world. Crossing along a bridge as tenuous as a lone plank between cliffs. In doing so, I find myself unwilling to return the way I came. Maybe that’s a necessity for genuine compassion? You should be altered by the encounter.

Jesus was in constant fellowship with those who’s reality differed greatly from His own. But often when compassion eludes me, it’s when I share the prerequisite experiences and resources. When I find myself frustrated that similar realities don’t yield the same approach to a situation. Shouldn’t they just get up and walk? Jesus had a very specific image for this.

At home after the ballet recital, I voiced my frustration to my wife, a physician: It was ridiculous to crawl like that. But she’d seen this woman walking around at ballet class and noticed her gait was awry, maybe because of severe hip dysplasia. And if so, then it would’ve been easier for her to crawl than to stand and walk. And possibly hardest to watch her daughter tendu and relevé and plié, knowing her own limitations would prevent her from ever sharing in that reality.

I think Jamison might say even meeting the prerequisites can sometimes obtund compassion as a plank left in the eye blurs sight. In those cases, it’s best I do a little crawling about in my world, looking for that piece of wood. It’ll make a good bridge.