Stubborn Patience in Paradise Lost

Joy and Matthew Steem

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Often, in an attempt to make me feel better, people will tell me that they are not very good with directions either. They mean well, but it doesn’t really help; it makes me feel like they think they understand, but they don’t. It can be somewhat isolating. So, when I meet someone who has a similar challenge it can be really quite bonding.

The petite elderly professor who taught me Paradise Lost was like that. One of her colleagues once told our class that said professor was so perpetually lost that it was sometimes an accomplishment for her to find her way home from a neighbour’s. True or not, the impression stuck and she became among my favorite instructors. When she spoke of Milton’s Satan, Adam, and Eve, I paid attention and was quite nearly riveted. Without power point, whiteboard, props or even a dramatic voice, the passages she pointed to were gripping. I still read it from time to time. The story fascinates me. I know the ending, how can I possibly be so transfixed, I sometimes wonder. I’m beginning to think I might have an inkling of what particularly fascinates me about the story: Satan.

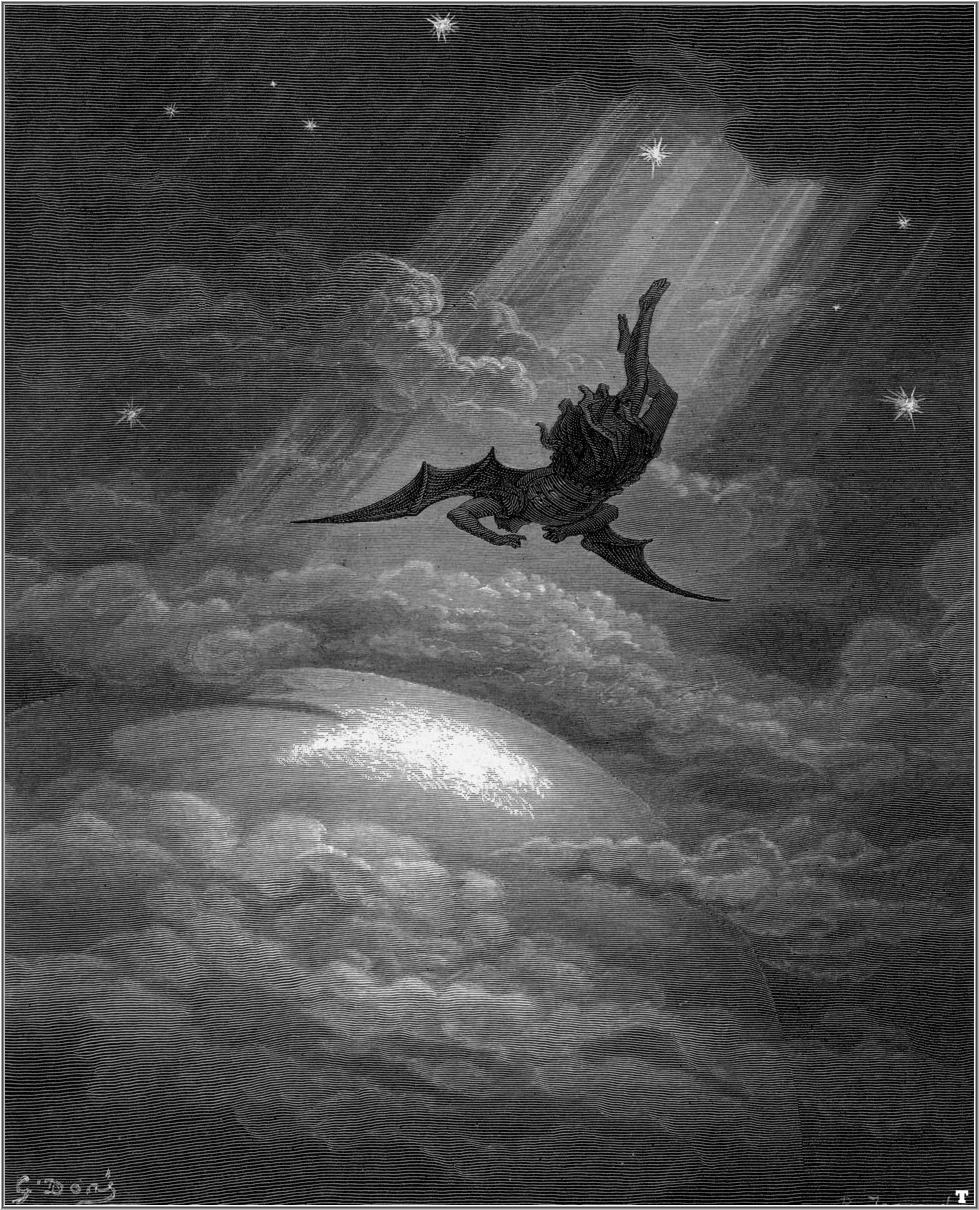

Perhaps of all the lines in Paradise Lost, the description of Satan’s “stubborn patience as with triple steel” is among the most chilling for me. The Fallen Angel’s designs to deceive and destroy God’s freshly created Eve and Adam stuns me with its icy resolution. It strikes me because of its dissimilarity with the nature of evil that I often see portrayed in culture and literature: hot, passionate, sensual desire with searing results. Milton, however, shows us a Satan who is not sexy, only stubborn.

Like Francis Underwood of House of Cards, Satan’s plans are strategic, stealthy and unwearied: his will is enduring and his resilience indestructible. Perhaps this image is so striking for me because of the composed calmness the line suggests he possesses. There is little hustle and bustle going on at this moment; instead, there is cold calculation. Rather than the perpetrator of forbidden fun like the devil (who can forget Al Pacino in this role) in Devil’s Advocate, Milton’s antagonist embodies the nature of evil Charles Williams explores in Descent into Hell: deliberate, incremental and isolating steps that go deeper and deeper into the non-spectacular: the anti-spectacular, in fact, for it is oblivion.