In a handful of the sky and earth,

In a handful of God,

We cannot count

All the ecstatic lovers who are dancing there

Behind the mysterious veil.

True art reveals there is no void

Or darkness.

There is no loneliness to the clear-eyed mystic

In this luminous, brimming,

Playful world.

–Hafiz, nineteenth century Persian poet

Artist Andrew Wyeth painted “Pentecost” in memory of a child in his Maine community who had been washed out to sea during a storm. “They couldn’t save her. I was thinking about the young girl’s body floating there underwater, and the nets became her spirit.”

Painting in the heyday of the mid-20th century fad of abstract expressionism, Wyeth was often criticized for the politically incorrect, dogged realism of his work. “More real than reality,” as one journalist of the day put it, referring to Wyeth’s intricate representations. The journalist is right without realizing it, for who can take in an exhibit of Wyeth’s paintings (which I had the privilege of doing on a white-white day last winter) and not be drawn in by the insistent expression of the unseen spirit breathing in all of them—whether tangled in the sparse grass of an ocean dunescape, glancing through diffused light on a stoic New England face, or coaxing our sense of wonder in the haunting way Christina on her hill leans upward toward… what, really?

“The wind blows where it pleases,” Jesus said. The Spirit is as real as anything we can see, swelling fishing nets and billowing through white curtains and drawing our eyes skyward for no reason at all. Its presence at our back can makes us turn around once again (compulsively and against our better judgment), to try to discover Who it is that persists in walking in silence at our elbow.

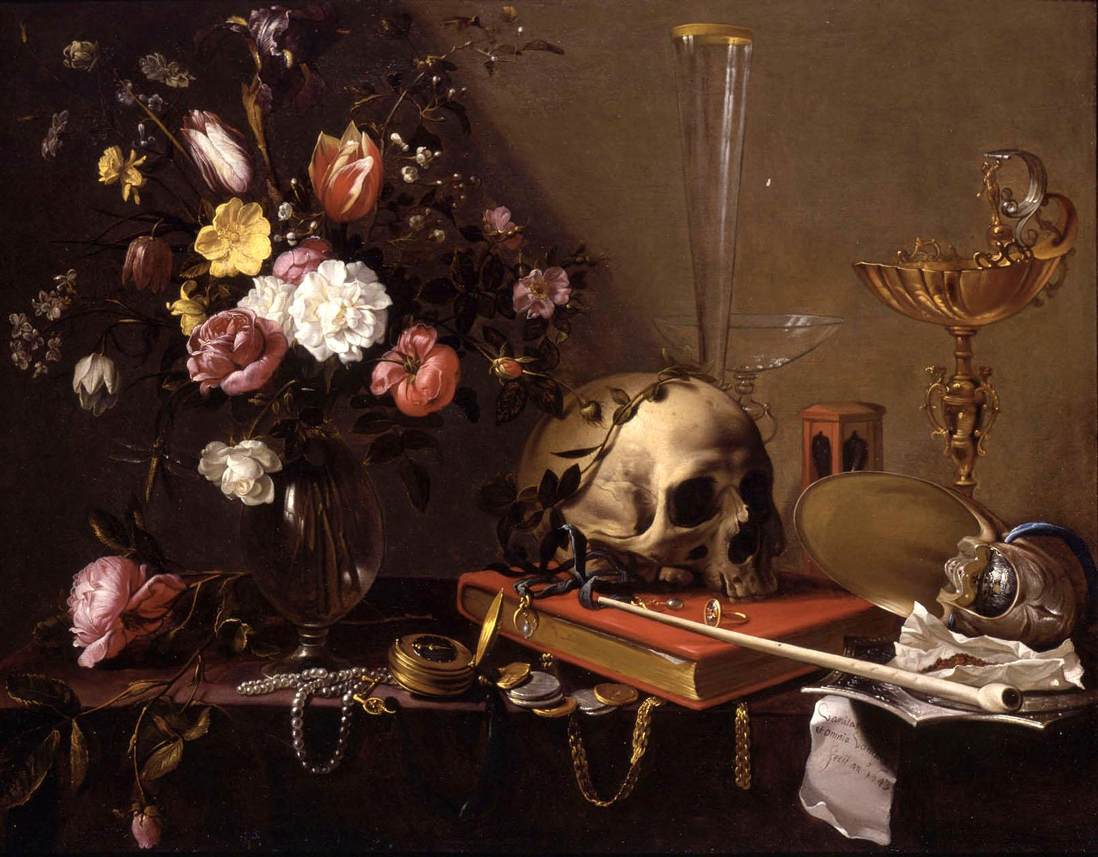

In a handful of God, all eternity resides, and the poet is right in saying that true art reveals there is no void or darkness. All the earth is a container for the divine, and Wyeth understood instinctively—as an artist though perhaps not a theologian—that for the innocent, drowned child, death had opened up to life. Ordinary, humble things are the first to fill up with the splendid, so that we might see and be reminded of what reality actually is.

Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap.

Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap. Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nothing Gold Can Stay

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

—

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

— Kiss me, and you will see how important I am.

—

Kiss me, and you will see how important I am.

—