Always Fair

Jayne English

When we have a good memory of our childhood, we shouldn’t visit it after we grow old. — Antonio

In the film Found Memories, Madalena lives in a small Brazilian village. The village’s former vibrance lies forgotten beneath peeling paint and rust. The handful of villagers are old and everything about them seems faded. They walk slowly up the hill to mass. They rarely talk. They eat in silence, the men play ring toss without speaking. The priest has locked the cemetery. Madalena says they have forgotten to die.

Madelena struggles to hold on to her memories. She writes a love letter every evening to Guilherme, her deceased husband. She writes just a few lines then folds the paper and puts it in a basket for safe keeping. “My love, I’d like to keep our memory forever alive, so our love, in the future, doesn’t suffer from the passing of time. We have to go beyond death, this cruel enemy, that didn’t choose day or time. I kiss you tenderly. Yours, Madalena.” She keeps their wedding photo in a closed-off room.

Rita, a young photographer, follows the empty railroad tracks to the village. She comes in like Mnemosyne, unlocking their memories and speech with each click of her camera. “I used to date a girl who looked like you,” says a man as she frames him in her lens. Rita is quick to remember. She watches Madelena make bread for the townspeople and says, “This town reminds me of the stories my dad used to tell.” Rita draws out Madelena’s memories. She retrieves her wedding photo for Rita, caressing it before hanging it back on the wall.

Early one morning, Rita takes a picture of Madalena in kerchief and nightgown. She shows Madalena who says, “Oh Lord.” Later, she carries her fresh baked rolls to Antonio’s shop. Usually they barely speak. Every morning he tells her to let him arrange the rolls in the cabinet. Every morning she insists on placing them herself. He calls her “stubborn old woman,” and she calls him “annoying old man.” But this morning Madalena asks, “Do you think I’m old?” “Old and stubborn,” he says nodding toward the rolls. She looks away and says, “My husband used to tell me, “Madalena, when I look at you, I don’t see you as you are. I see you as you were, when you were 20, and we got married. This is how I see you.”

Sipping their coffee outside, Antonio tells her, “When I was young, I had a girlfriend who died when she was 18. Thank God I never saw her grow old. Because when I remember her, I’m 18 as well.” But when he adds how we shouldn’t revisit childhood memories, Madalena asks, “What’s left then?” “Us!” he says. To which Madalena replies, “Would you mind being quiet for a while.”

Madalena confides to Antonio that she’s afraid to die. But her returning memories are changing her. She smiles, she doesn’t wear a kerchief as often. Her wrinkles seem to fade framed by her thick hair.

The priest had locked the cemetery as if he thought forgetting the past would help his old flock bear the burdens of age. He shared Antonio’s view that the past is best left behind. But Rita develops pictures from the negative of Antonio’s statement. When the villagers remember the old gifts of loved ones and youthfulness, they discover new ones – they talk to each other and become more intimate. They celebrate, dressing up and dancing outside to favorite old songs on the victrola.

In his poem “Former Beauties,” Thomas Hardy writes of middle-aged women in the market and tries to reconcile their present looks with their former beauty: “Are they the ones we loved in years agone, / And courted here?” He wonders if they remember the vows the young men made to them “In nooks on summer Sundays” and dancing on the green until moonlight. He ends the poem with this stanza:

They must forget, forget! They cannot know What once they were, Or memory would transfigure them, and show Them always fair.

In Found Memories, the villagers had locked up the past. It was as if they couldn’t live and they couldn’t die. When they woke to their former joys, they were “transfigured” into people who danced on the green again.

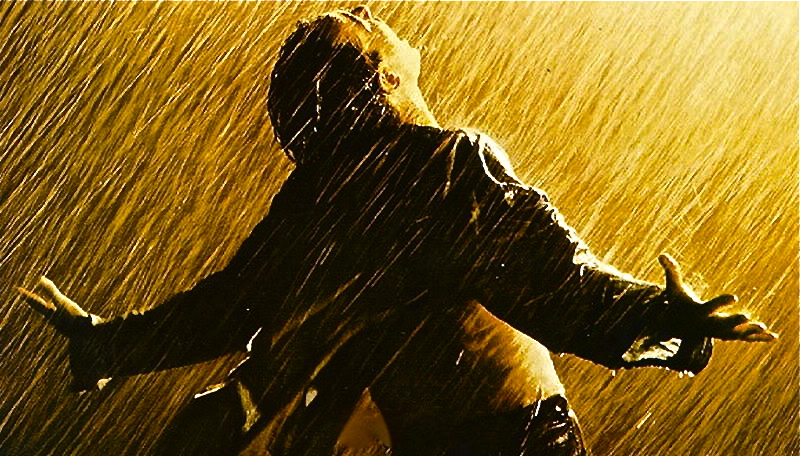

Before Madalena’s death at the end of the movie, Rita takes one more photograph. Madalena’s hair is down, full and wavy. We know by her bare shoulders and a self-conscious look on her face, that she is naked. As she stands before Rita’s camera, her expression transforms, she looks “always fair.” Her smile is expectant like a bride waiting for her bridegroom.