The Grip of Entertainment

Michael Dechane

I went to a casino for the first time several weeks ago. I am as numb to stimuli as the next person, but in that place, I felt an extreme sensory overload. Bright, flashing, loud, smoky, and crowded, every sense assaulted. Curiosity and excitement melted into confusion—I had no idea how to do nearly anything in that place—and then into a sadness that reminded me very much of how I eventually came to feel about strip clubs, about 15 years ago. I lost what little money I committed beforehand to losing in about half an hour, mostly over a half-dozen hands or so of blackjack. I wandered outside into the cold, clearer air and began earnestly trying to justify to myself the urge to get a little more cash out of a little machine that sponges dollars from far away bank accounts so I could play a little more. That’s all I’m doing here, I told myself: just playing. The signs everywhere confirmed this: we are all here just for entertainment’s sake, just for fun, you see. Later that night, riding home with my old friends I spoke up out of a prolonged silence: “That was a great place to make some terrible decisions,” I said.

I went to a casino for the first time several weeks ago. I am as numb to stimuli as the next person, but in that place, I felt an extreme sensory overload. Bright, flashing, loud, smoky, and crowded, every sense assaulted. Curiosity and excitement melted into confusion—I had no idea how to do nearly anything in that place—and then into a sadness that reminded me very much of how I eventually came to feel about strip clubs, about 15 years ago. I lost what little money I committed beforehand to losing in about half an hour, mostly over a half-dozen hands or so of blackjack. I wandered outside into the cold, clearer air and began earnestly trying to justify to myself the urge to get a little more cash out of a little machine that sponges dollars from far away bank accounts so I could play a little more. That’s all I’m doing here, I told myself: just playing. The signs everywhere confirmed this: we are all here just for entertainment’s sake, just for fun, you see. Later that night, riding home with my old friends I spoke up out of a prolonged silence: “That was a great place to make some terrible decisions,” I said.

I didn’t really get angry until the next day, in the morning as I had my coffee and journaled and tried to sort out the previous night’s expedition. All the signage about entertainment is what got me, gets me still. I saw faces of people likely having a great time. I saw others that I’m sure were hiding ruin and addiction and wreckage I can’t even bear to imagine much about. “Entertainment” comes to us by way of the late Middle English, before that, the French, and on back to some glued up Latin. “Among” and “to hold.” I don’t know how to put those things together, but the last bit arrests, holds me: we are entertained when we are held by something. When our eyes, mostly, are held by something, and they, in their turn, hold onto something else: let’s say our attention, let’s say our hearts. Let’s say awe diluted to silent gorging; let’s say wonder diminished to wandering curiosity; let’s say praise transmuted into bastardized worship: we cheer and call for more and more, already on our knees and we know not who our Daddy is, as we are entertained, just here for some fun, held, among others, in whatever audience.

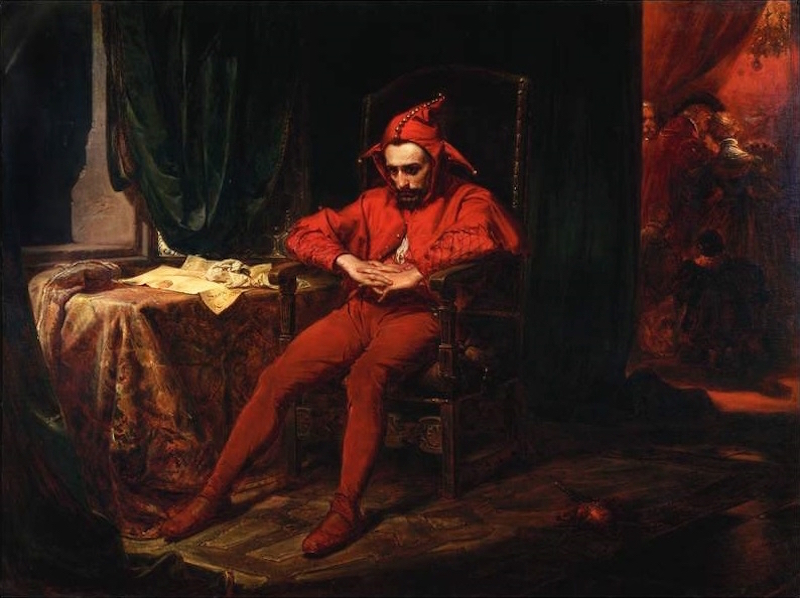

I think “entertainment” and I think first of a king slouched on his throne, bored in his court, who calls for his jester. I don’t care about the jester or his act right now, it’s the king I see: him who does not see, who will not look out on what he has been given to rule. He would see only problems to be dealt with, if he did, or faceless subjects with nothing to offer him but troubles and a dirty throne room floor. He cannot delight in what is his, so bring me someone, bring me something that will at least amuse me, if delight is so out of the question, he roars, and enter the jester in his suit and bells. He is a foolish king, I see, and false to his calling, his kingdom, even to his bored and all too human self.

And then I imagine what I cannot see: how unlike him the King is. The one who sees and is not bored. The one who cares most deeply for what he has made, and what he rules, and what he was given. The King that will not be held by any one or thing against his will and yet sits enthroned and arrested by his children he delights in, calling them before his throne, name by name.