The Eighth Day and Calvary

Tom Sturch

This week many Christians will observe Eighth Day services, or The Octave of Christmas. The Eighth Day signifies the dawning of the New Creation of Christ's reign. It is fitting that we celebrate a new year during this time and plan our fresh starts. Eight is the number of new beginnings in Hebrew numerology. God made eight covenants with the children of Abraham. There were eight people on Noah's Ark (2 Peter 2:5) and Jewish boys were circumcised on eighth day from their birth (Genesis 17:10). Luke 2:21 is where we see the rites of the eighth day celebrated in Jesus' life and is the primary reason for its observance. And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus... In the style of a royal birth announcement, Luke foreshadows who the boy will become. In the child's name, he will be Savior, and in the shedding of innocent blood he will be the perfect atonement.

This week many Christians will observe Eighth Day services, or The Octave of Christmas. The Eighth Day signifies the dawning of the New Creation of Christ's reign. It is fitting that we celebrate a new year during this time and plan our fresh starts. Eight is the number of new beginnings in Hebrew numerology. God made eight covenants with the children of Abraham. There were eight people on Noah's Ark (2 Peter 2:5) and Jewish boys were circumcised on eighth day from their birth (Genesis 17:10). Luke 2:21 is where we see the rites of the eighth day celebrated in Jesus' life and is the primary reason for its observance. And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus... In the style of a royal birth announcement, Luke foreshadows who the boy will become. In the child's name, he will be Savior, and in the shedding of innocent blood he will be the perfect atonement.

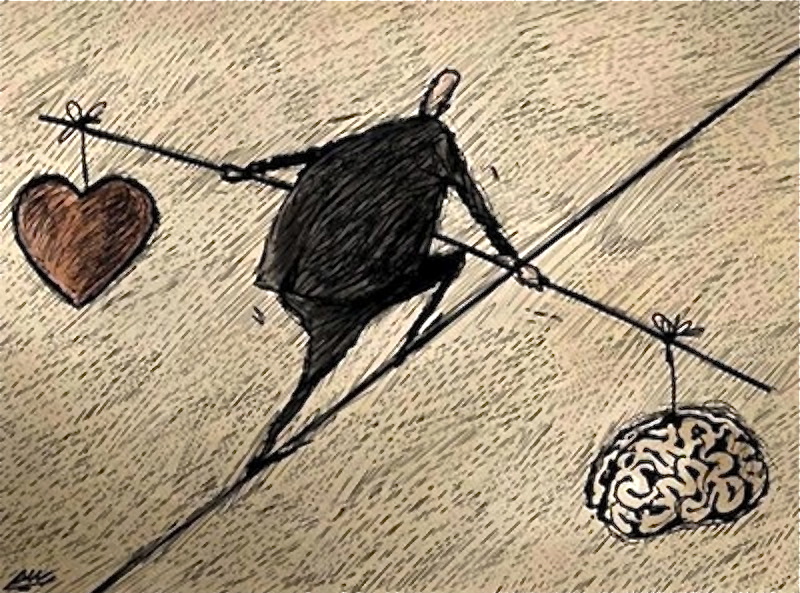

There is a culturally persistent notion that something is wrong and that blood must be shed—that someone must pay. In history, human and animal sacrifice and the penal system all stem from this moral dilemma. It is a subject of great works such as Atonement, The Dead, and Wuthering Heights. Pernicious and unrelenting, it stalks us now in the black and white of the daily news. Its accusations drown our cries for justice. No matter our plans or successes, despite our rituals and good works, it remains. It waits at every door. It says that things can only be made right with restitution of the greatest treasure and with the penalty of a life. And we wonder who will pay? Who can pay?

In Calvary, writer/director John Michael McDonagh wastes no time plunging us into this desperate world. The movie opens with Father James Lavelle dressed in an old-fashioned black soutane and white collar reading Moby Dick in his confessional booth. Someone steps into the adjoining booth and confesses that at the age of seven he was raped every other day for five years by a Catholic priest. “There was a lot of blood,” he said.

LAVELLE:

I don’t know what to say to you. I have no answer for you, I’m sorry.

MAN’S VOICE:

What good would it do anyway, if he were still alive? What’d be the point in killing the bastard? That’d be no news. There’s no point in killing a bad priest. But killing a good one? That’d be a shock, now. They wouldn’t know what to make of that. (pause) I’m going to kill you, Father. I’m going to kill you ‘cause you’ve done nothing wrong. I’m going to kill you ‘cause you’re innocent. (pause) Not right now, though. I’ll give you enough time to put your house in order. Make your peace with God. Sunday week, let’s say. I’ll meet you down on the beach there. Down by the water there. (with a laugh) Killing a priest on a Sunday. That’ll be a good one.

Against the beauty of an Irish seaside village, McDonagh gives us eight days with Father James as he ministers to a cynical, flattened human universe where escape is distraction and suicide is made rational. His aloof invulnerability masks the gross presence of mortality as he gently serves a flock too self-absorbed to desire it until the end when he decides what must be done.

This movie is appropriately rated R for giving a real and frightening look at ourselves and providing the dark background for the light of hope that ought shine in us. I do not agree with the movie's tragic outcome, but it, too, is a common falsity prevalent in the world. We can no more author our own salvation than be the atonement for the sin of another. But the movie's hard questions are a good place to start the year. I'll make my resolutions with them in mind toward preparing myself to give a hope-filled answer.