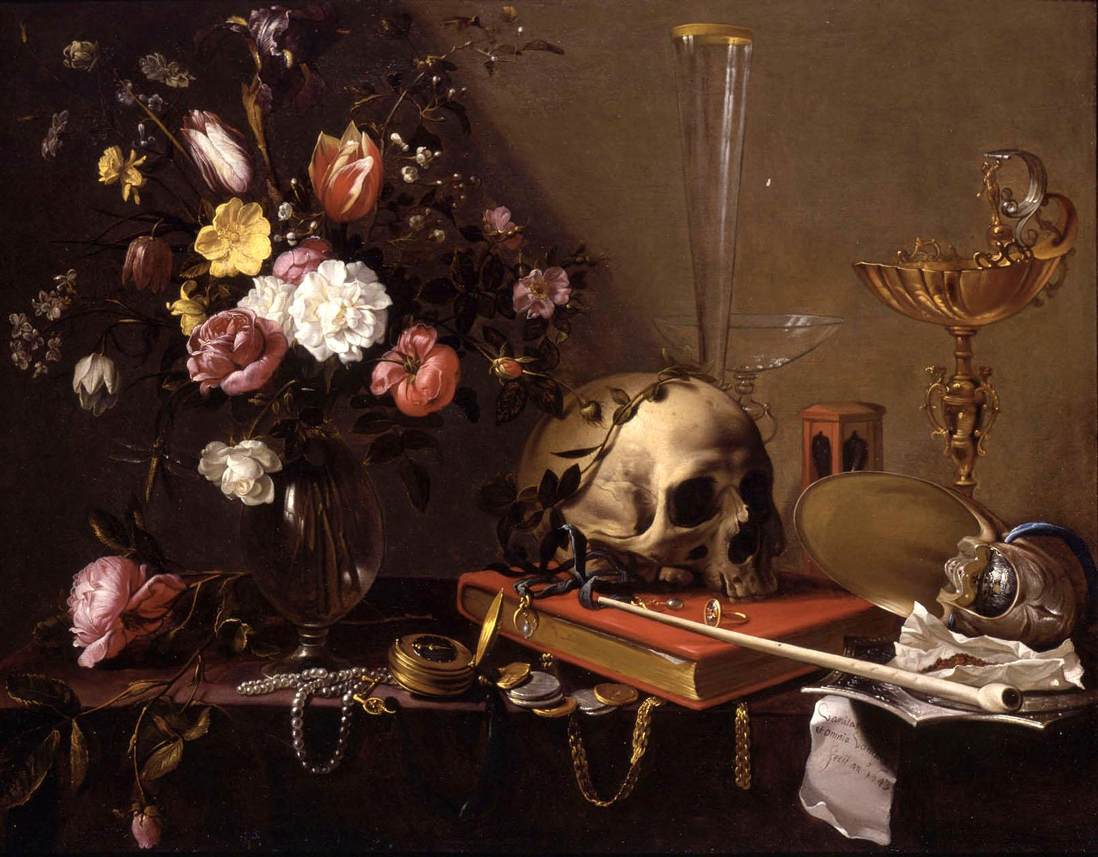

A Defense of Skeletons

Jean Hoefling

The truth is that man’s horror of the skeleton is not horror of death at all. It is man’s eccentric glory that he has not, generally speaking, any objection to being dead, but has a very serious objection to being undignified. And the fundamental matter which troubles him in the skeleton is the reminder that the ground-plan of his appearance is shamelessly grotesque. - G.K. Chesterton, "A Defense of Skeletons"

In his quirky essay, Chesterton writes of walking through woods where the forest folk kept apologizing that it was winter and the trees were bereft of foliage. “There was evidently a general feeling that I had caught the trees in a kind of disgraceful dishabille and that they ought not to be seen until, like the first human sinners, they had covered themselves with leaves.” We’re a lot like those peasants regarding our own souls, trying to appear more clothed and commendable than we are, knocking around with planks sticking out of our eye sockets while we swipe at someone else’s dislodged eyelash with a bony phalange and hope no one mistakes us for a character in Saint-Saëns tone poem, Danse Macabre. (See St. Matthew 7:3) Yet deep down we know that when death strips us of the pretty outer wrappings, our “shamelessly grotesque” frame will be exposed by the likes of devouring worms.

How little of grace we understand. For if our hearts were more gripped by grace, we might not only be less shy about our undignified skeletons, but waste less energy in denial about the inevitable core of our human nature. Who knows, laughing at our souls’ bare bones might be just the thing that begins to heal our poorly disguised pride.

As an example, I give you my recent preparation for the Sacrament of Confession. I wrote out my tiresome, amateurish sins on a 3x5 card as usual, using a pencil (badly in need of sharpening) so that I could tweak my wording. Somewhere down the list I wrote, “I’ve been jealous of another’s life.” What nonsense. It isn’t the other’s life I’m jealous of; I have one of my own. And who is this ambiguous “another?” I forced myself to erase and rewrite the embarrassing truth: “I’ve been chronically jealous of a close friend’s wealth and opportunities.” How petty the words looked on paper, how undignified. Still, I felt a twinge of elation in my brute honesty, blurted out the next day at church before the icon of Christ while the priest stood by. For in my insistence on specifics I had momentarily conquered that eccentric glory Chesterton talks about, that tendency to grope for coverings to hide the truth of what I am. And I take heart that someday I might be comfortable enough with my skeleton that I can boldly dash off concise sins of omission and commission with an expensive pen that doesn’t skip ink, and without hesitation. “Let our sins be strong,” Martin Luther said. And let our willingness to admit them for what they actually are be stronger still.

Afterward, I turned from the icon and went my way, vaguely amused. I forgot to look into its glossy surface to see whether a reflection of my own skull was grinning back at me.