I have often heard people who read Chesterton say that despite the expenditure being a mite difficult, reading him was something most definitely delightful. Perhaps this is because Chesterton has the uncanny ability to rephrase a thought or concept in an untraditional way—through a new lens. In many ways I find this helpful since it enables me to rethink what I previously assumed had already been soundly concluded. Either way, looking through the Chesterton lens is often rewarding. And more often than not, the G.K aperture captures a very large region of thought. Plus, Chesterton himself simply refuses to be narrowly labelled or simply catalogued. I suppose, if asked his category of choice, he would quickly and loudly respond “orthodox,” but then even that word would have to be greatly expanded since for many it simply means conservative. And orthodox certainly isn't just that.

I have often heard people who read Chesterton say that despite the expenditure being a mite difficult, reading him was something most definitely delightful. Perhaps this is because Chesterton has the uncanny ability to rephrase a thought or concept in an untraditional way—through a new lens. In many ways I find this helpful since it enables me to rethink what I previously assumed had already been soundly concluded. Either way, looking through the Chesterton lens is often rewarding. And more often than not, the G.K aperture captures a very large region of thought. Plus, Chesterton himself simply refuses to be narrowly labelled or simply catalogued. I suppose, if asked his category of choice, he would quickly and loudly respond “orthodox,” but then even that word would have to be greatly expanded since for many it simply means conservative. And orthodox certainly isn't just that.

In fact, Chesterton spoke out against many an aspect of conservatism. Actually, when it came to capitalism, the vitriol he uses is nearly startling. (“Starling” due to the most unfortunate truth that for many—including me, though it’s changing—the word “Christian” is often linked to conservative, and conservative is linked with capitalism. A truly nasty bit of connection.) Anyway, I was surprised then when I first saw his use of the word “Latitudinarian.” If you go to Google and type in the word “latitudinarian,” you will see the following words:

Latitudinarian was initially a pejorative term applied to a group of ... theologians who believed in conforming to official Church ... practices but who felt that matters of doctrine, liturgical practice, and ecclesiastical organization were of relatively little importance.

And if you search for “latitudinous,” you will get: having latitude, scope, range, breadth, etc., especially of ideas, interests, interpretations, or the like.

Sounds really quite nice, doesn't it? It sounds positively inviting and timely, even. I mean, in terms of the ecumenical movement, it sounds downright attractive. And in terms of mindset, it seems more than just helpful. The more latitude of thought, the better the perspective and ability to appreciate things. Yet every time Chesterton uses the word latitudinous, it is in a pejorative manner—like a lot.

But then again, Chesterton has a way of viewing things differently. So when it comes to largess of breath and range and all that, here is what bothers Chesterton about being overly latitudinous: since the nature of the world is circumscribed by limitations—and we know that our acts of volition (to choose to act in a certain way, whatever it is) will necessarily mean that we will be rejecting some other action—there must be limits even to breadth.

So is it sensible to have a wide perspective? Absolutely. But even with this, there must be limits. In his Orthodoxy, Chesterton says that as in life, in art there are laws and limits.

If you draw a giraffe, you must draw him with a long neck. If, in your bold creative way, you hold yourself free to draw a giraffe with a short neck, you will really find that you are not free to draw a giraffe. The moment you step into the world of facts, you step into a world of limits. You can free things from alien or accidental laws, but not from the laws of their own nature. You may, if you like, free a tiger from his bars; but do not free him from his stripes. Do not free a camel of the burden of his hump: you may be freeing him from being a camel.

Thus while having latitude is good (we must have an expanded enough vision to appreciate variation and variety), we must always maintain the ability to have distinctions. Namely because, when breadth trumps distinction, nothing can be really distinguished, and then, of course, there is an inability to perceive variety. And what is the spice of life? Why, it is variety, of course.

[Some sources for Chesterton’s view on limits and latitudinarians can be read in greater depth from his grand Orthodoxy, and from the following essays: “About Shamelessness,” “Rabelaisian Regret,” “The New Theologian,” and “The Flag of Thought.”]

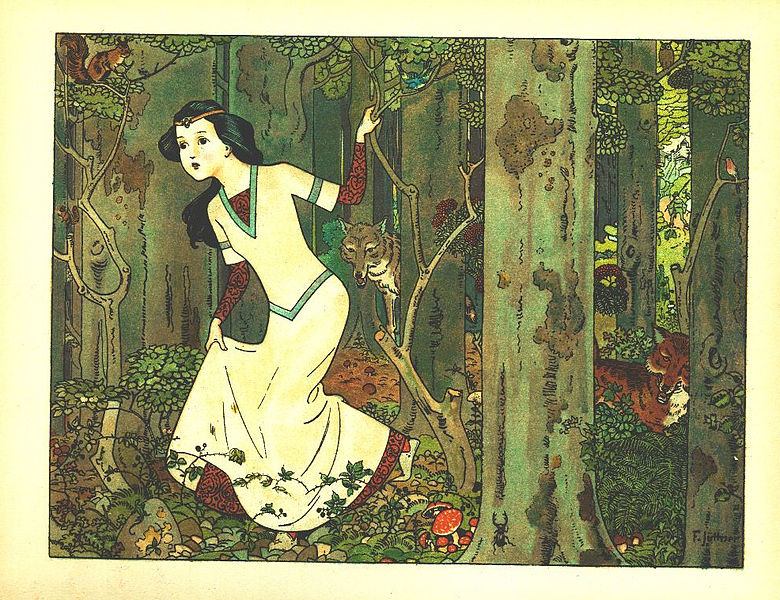

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment. Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with  On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —