Dylan: The Times They Are A-Changin’

Jayne English

“Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now."

—Bob Dylan

“Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now."

—Bob Dylan

My brother began listening to Dylan when he was 17. That means I heard iconic lyrics like: “Well, they’ll stone you when you’re tryin’ to be so good/They’ll stone you just like they said they would” and “Once upon a time you dressed so fine/You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?” drift through the house when I was 14. The guitar and harmonica, Dylan’s sometimes smooth, sometimes raspy voice wove their way through my mind and for years resided in the grooves of fond memory. I was immersed in “Blowin’ In the Wind,” “Tamborine Man,” “Lay Lady Lay,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” as they spun their familiar sounds from the turntable. Recently, feeling homesick for those songs, I listened to them again. I was surprised to find that the Dylan I knew opened to new and deeper levels.

It wasn’t just that I was older. During this same time I went back to listen to other music I inhabited as a teenager. Returning to Carole King and Carly Simon, for instance, felt just the same as it did in the past. But Dylan’s music now spoke in ways I never heard before. How is it that even his old songs can still be fresh today? Italian author Italo Calvino offers a simple point about what makes a literary classic: “A classic is a book which has never exhausted all it has to say to its readers.” Dylan’s work is new over time because it is deeply meaningful.

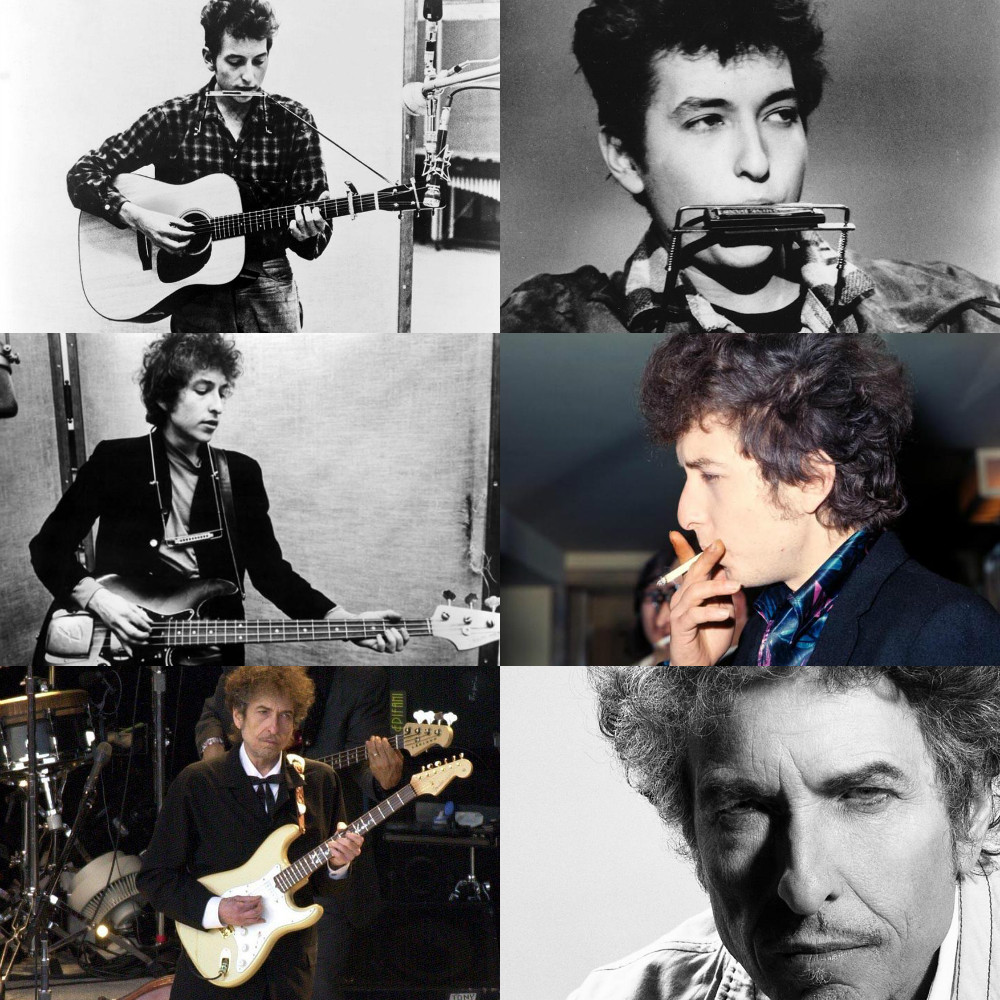

It continues to have something to say because Dylan has always been open to change, not holding himself to a constraint others wanted to impose. He got a lot of grief for it. He was constantly moving artistically, from writing topical songs like Woody Guthrie’s, to protest songs, to flashing image songs, and he famously switched from acoustic to electric guitar. He probably would never consider himself brilliant, but there is brilliance in his lyrics, music, and knowing not to hold onto categories, but to allow himself the freedom to chase change and ambiguity.

Dylan’s style could change because he is true to his inspirations. Among the many are Herman Melville, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, Dylan Thomas, Arthur Rimbaud (“When I read [Rimbaud’s] words the bells went off.”), and Paul Verlaine.

After passing through the familiarity of nostalgia, I found in Dylan so much of the poetic soul of the Beats. When he was 18, someone gave Dylan a copy of Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues. Dylan said the book blew his mind. When poet and friend Allen Ginsberg asked him why, Dylan told him, "It was the first poetry that spoke to me in my own language." Ginsberg continues to explain Kerouac’s influence on Dylan: “So those chains of flashing images you get in Dylan, like ‘the motorcycle black Madonna two-wheeled gypsy queen and her silver studded phantom lover,’ they're influenced by Kerouac's chains of flashing images and spontaneous writing.” In Dylan’s “Desolation Row” (1965) he blends these images and more: beauty parlor, circus, Bette Davis, Romeo, Hunchback of Notre Dame, iron vest, Noah’s rainbow, Einstein, a monk, pennywhistles, and mermaids. The Beatles were taken with Dylan’s lyricism and style. George Harrison says of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album, "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful."

As his audience attempted to confine him, Dylan resisted with all his creativity. In a 1966 Playboy interview, Dylan is asked, “Mistake or not, what made you decide to go the rock-'n'-roll route?” Dylan responds with an explanation that was more like an improvisational riff. He spun a tale of images that included a card game, crap game, pool hall, Mexican lady, Charles Atlas. It flows in a pastiche of people and plots and scenes. When he’s finished, the interviewer says, “And that's how you became a rock-'n'-roll singer?” Dylan replies, “No, that's how I got tuberculosis.” Dylan talks in imaginative circles and was often considered “contrary” by journalists because he knew that many people were not willing to listen to, and probably would not understand, his views on the artistic process.

In the same 1966 interview, Playboy reminds Dylan that he told someone he had done everything he ever wanted to do. “If that's true,” the interviewer asks, “what do you have to look forward to?” Dylan replied, “Salvation. Just plain salvation.” Dylan’s work, as it continues to speak, does offer a kind of salvation. As one author puts it, “it is in the nature of beauty to suggest the divine and the eternal.” I’m so glad I followed nostalgia’s pull to Dylan and found more of the place where beauty saves the world.