From a Place of Anger

Aaron Guest

I write this from a place of anger. And I think it’s a good place for me to write from.

I write this from a place of anger. And I think it’s a good place for me to write from.

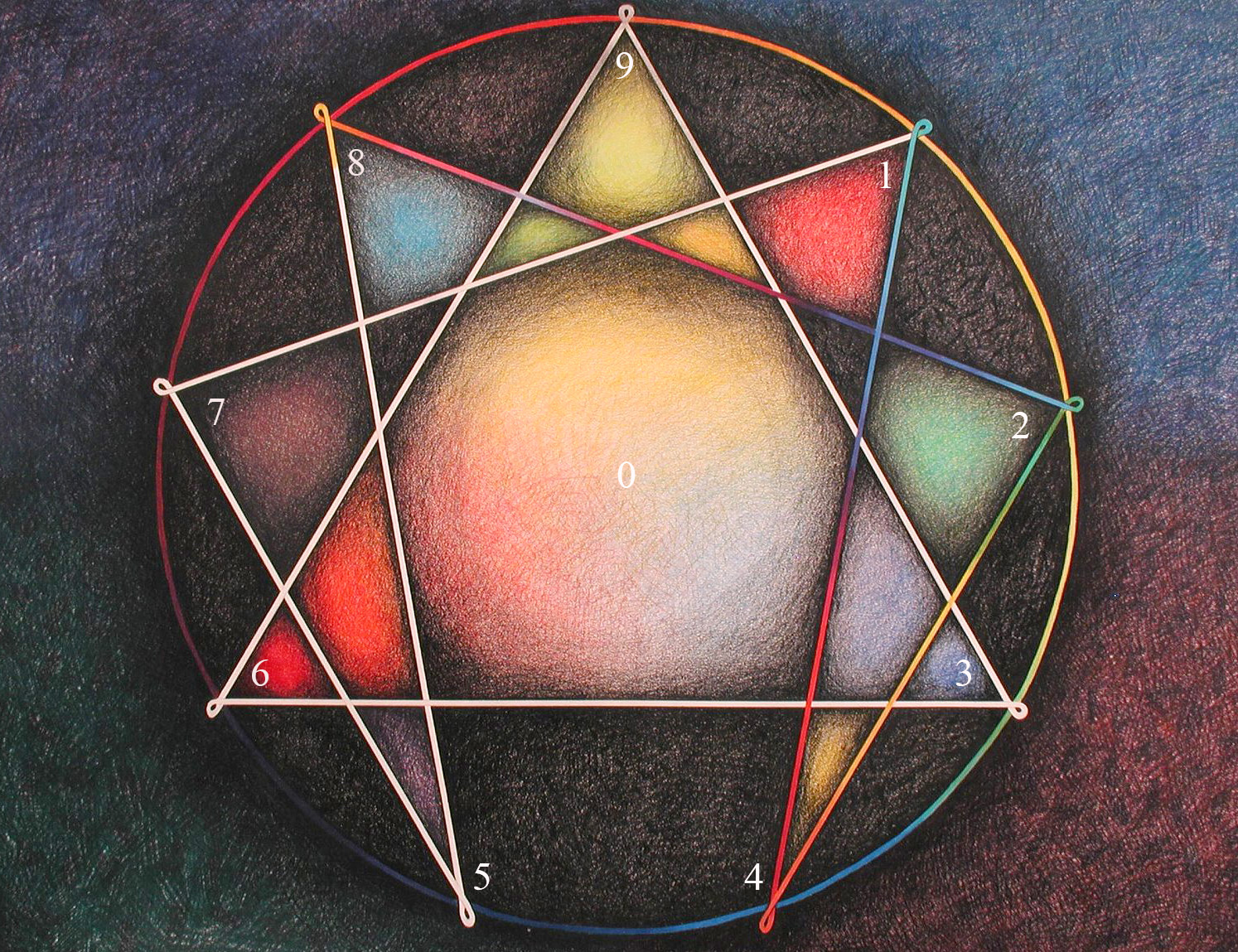

Over the past two years I’ve been able to invest more time into understanding myself. It began when a friend introduced me to the Enneagram. It’s a personality test that assigns one of nine “types” to people based solely on their motivations. From “The Perfectionist” to the “The Peacemaker”, it definitively accounts for the way I, and others, behave.

The Road Back to You is a sublime primer on the Enneagram. Written by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile, it’s witty and informational and I highly recommend it. The book explains the way the Enneagram demonstrates the spontaneous and unpredictable beauty of being human, and how it can flourish and flounder in a predictable away.

Discovering my type has changed the way I understand myself. For example, as a 9 (“The Peacemaker”), when it comes to anger I have an innate ability to dissolve it. To bury it and effectively pretend that it wasn’t a big deal. Sometimes it’s not. But sometimes it is. Like today. The day after the election. This is a big deal and it can’t ever not be.

I also have this incredible ability to put everyone’s desires ahead of my own. I rarely ask myself what I want to do. None of these are de facto negative qualities, but they can be. And my tendency is to let them cripple me. To let them prevent me from doing something, from speaking up.

The Enneagram has also shown me how the people closest to me are very different from me. None of us are the same types. And the Enneagram is at it’s absolute best when it’s showing how the types respond to each other in relationships, in decision making, in conversation. It has become the single most useful tool to help me listen and understand the people around me. We are different. We are each our own type, with our own motivations for action and inaction, for decision and indecision, for happiness and sorrow. The Enneagram advocates for empathy. It lights a path to loving our neighbors in a very real and bright way.

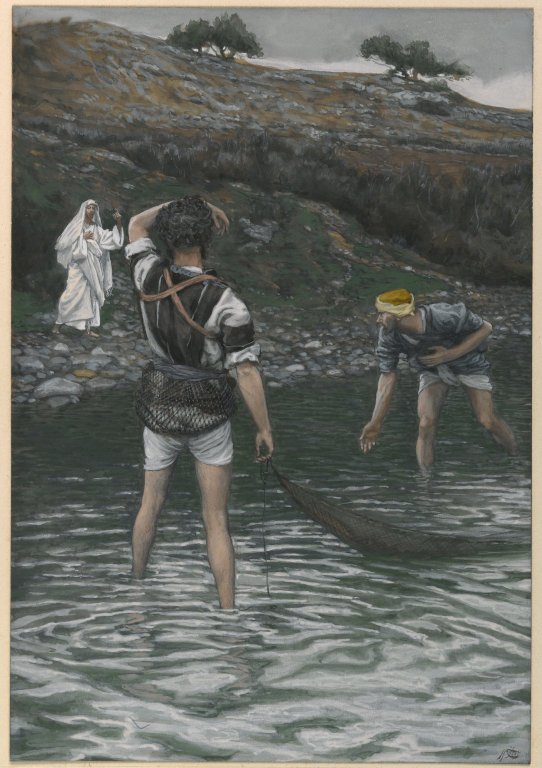

One day soon I will see that the evangelical church I am angry with is made up of different people, with all types of wants and fears. But today, in the days after election day, the Enneagram is teaching me about being honest with my anger. To kick over a few tables—to borrow from a famous scene in the Gospels. American evangelicalism has made a mockery of my faith.

So much of my life as a Nine is to seek peace. To deny my anger because it brings disharmony to my life. But, what looks like my desire for peace is really just a desire to shy away from conflict. Should I pray that this anger translates into action? As a nine, when I move toward action because of anger, I enter into a state of becoming. I awake, soul intact and strong and true, into a better person. And I realize that behind all true peace there must be pain and conflict. As Fr. Richard Rohr says, “The only way to overcome the bad is to be the better.”

May I need to want to be better. May I need to want to not be scared. May I need to want to speak up and fight and change this.

Lord, let me stay angry.

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever  Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:  I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.  On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —  I tag along with my wife to her work functions, mingle with people whom I am trying desperately to assign names to faces. I get the question often enough. And it’s begun to rattle me like empty dinner glasses.

I tag along with my wife to her work functions, mingle with people whom I am trying desperately to assign names to faces. I get the question often enough. And it’s begun to rattle me like empty dinner glasses. The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s

The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s  As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”.

As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”.