CA Redemption Value

Michael Dean Clark

A homeless man in his fifties pulls aluminum cans from the trash barrel in front of the Ralphs Supermarket where I shop. He’s clearly no amateur. What catches my attention this morning is not the act itself. He’s not the only person I've seen scavenging to get by today. This is Ocean Beach after all.

What arrests my general distraction is the way he cleans as he pulls the cans out of the refuse, taking time to pick the cigarette butts out of the ash tray on the top of the stone-speckled trash barrel, dropping them one by one into the bag as if to earn the recycling fees others didn't bother taking the time to redeem.

-#-

When I was a reporter in Los Angeles, I worked for a newspaper that covered the Puente Hills Landfill in a strip of unincorporated county land that was once most likely a dairy farm. Now, it’s America’s largest trash heap at 150 meters tall and covering more than 700 acres. I once covered a meeting where officials discussed the rate at which the massive trash mountain was summiting the space allotted to it. At one point in the meeting, a plan to ship the region’s trash by rail into the Nevada desert was discussed, though not seriously. Apparently, the same objection came up every time the concept was mentioned. It’s less expensive (and thus, more profitable) to continue with the current business model until it is no longer viable.

No word on how viable the people of Nevada find the alternative.

-#-

I love family stories, especially the ones from before I was born. Apparently, there was a DIY trend in the early 70s where particularly resourceful interior design types would piece together area rugs from a number of smaller pieces of (hopefully) corresponding color, though I did mention this was the 70s, right? In my mind’s eye, it’s like a shag quilt. All one needed were the remainders of other pieces of plush pile or low nap and the desire to turn said scraps into one Franken-rug.

My parents apparently harbored said desire, which is why, on more than one occasion, you could find my older brother in the dumpster behind a carpet store. I’m told the results were lovely, though no pictures exist as confirmation.

-#-

I may be over-simplifying, but as I relive these scenes I can’t help but see the writing in them all.

Michael Dean Clark is the fiction editor at Relief, as well as an author of fiction and nonfiction and an Assistant Professor of Writing at Point Loma Nazarene University. He lives in San Diego with his wife and three children.

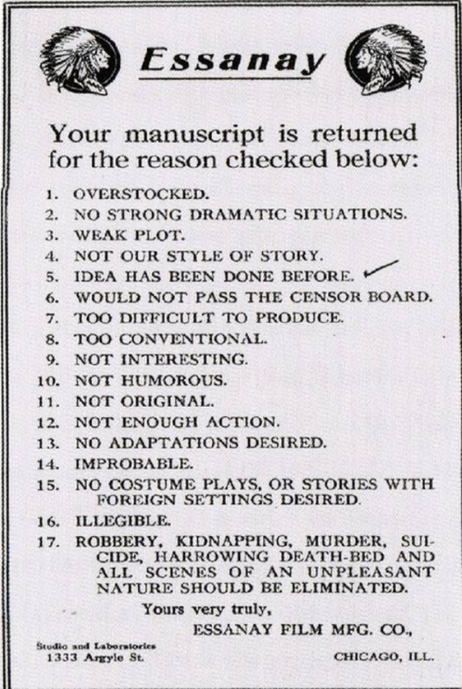

Rejection always hurts, but this publisher seems particularly hard to please! This vintage rejection slip is from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company (1907-1925), who is famous for their production of Charlie Chaplin movies (Photo originally posted on

Rejection always hurts, but this publisher seems particularly hard to please! This vintage rejection slip is from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company (1907-1925), who is famous for their production of Charlie Chaplin movies (Photo originally posted on