When I sit down to write, I pretend I am speaking at an event. I’m the plenary at the Festival of Faith and Writing, for example. Or I’m giving my acceptance speech for this year’s Newbery Award. Once, I pretended I was giving the commencement speech at the University of Notre Dame. I was never a student there, but I did teach step aerobics and my inspiring, motivational, and encouraging personality led the university to request my presence at graduation. In my fantasy, they would be giving me an honorary doctorate. For teaching aerobics.

When I sit down to write, I pretend I am speaking at an event. I’m the plenary at the Festival of Faith and Writing, for example. Or I’m giving my acceptance speech for this year’s Newbery Award. Once, I pretended I was giving the commencement speech at the University of Notre Dame. I was never a student there, but I did teach step aerobics and my inspiring, motivational, and encouraging personality led the university to request my presence at graduation. In my fantasy, they would be giving me an honorary doctorate. For teaching aerobics.

I came up with the idea to pretend in order to write in the spring of 1998. I was in a study carol in the library at Calvin College. I was supposed to write a term paper for Dale Brown’s American Literature class, and my usual treats, a large bag of gummy worms and a Poor Man’s Mocha (a mixture of coffee and hot chocolate that cost me fifty cents), were not providing the jumpstart I needed to pick up my pen and write.

I was probably supposed to explore a theme in my paper. But it’s been a minute since 1998 and I don’t remember the exact assignment. What I do remember is sitting in Dale Brown’s class on the first day of my last semester of college and hearing him quote Toni Morrison’s Beloved: “Anything coming back to life hurts.”

Crap, I thought as I wrote that sentence down and circled it. I was interviewing for teaching jobs in South Bend, Indiana where my fiancée was a graduate student. I was looking for a wedding dress with enough tulle that would make Scarlet O’Hara both approve and be envious. I was wondering if my soon-to-be husband would agree to living in an apartment by the St. Joseph River. I wasn’t interested in the idea that we are only fully alive if we are in pain. No thank you, I thought, as I shifted my left hand so the diamond on my ring sparkled.

Morrison’s words were the first notes I took in American Literature. I still have the navy blue Mead notebook. The letters from the sentence and the circle around it are shaky, not my typical neat handwriting. That’s because I trembled when I wrote them.

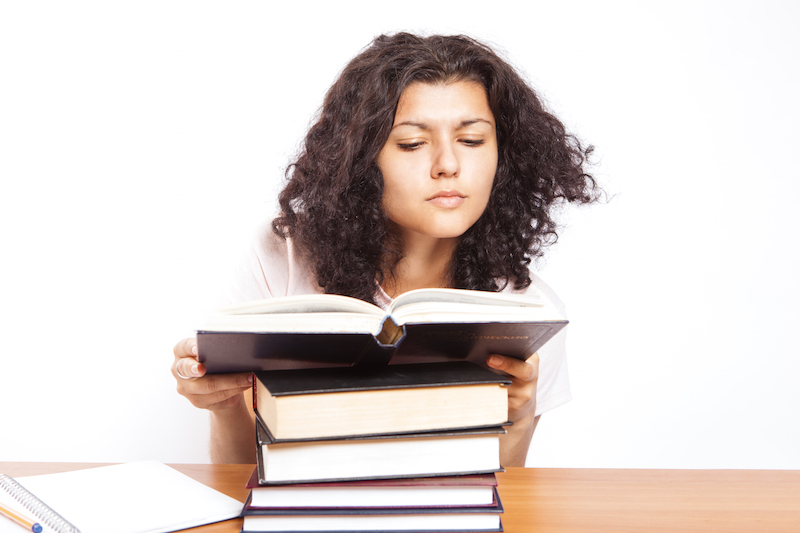

And I trembled when I read the stories Brown assigned for class: “A Soldier’s Heart,” by Ernest Hemingway, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” by Flannery O’Connor. They all bothered me. I walked around that semester feeling as though I’d just been shocked by the morning alarm after being in a deep sleep. I felt like I needed to figure out where I was and what I was supposed to do now that I was awake.

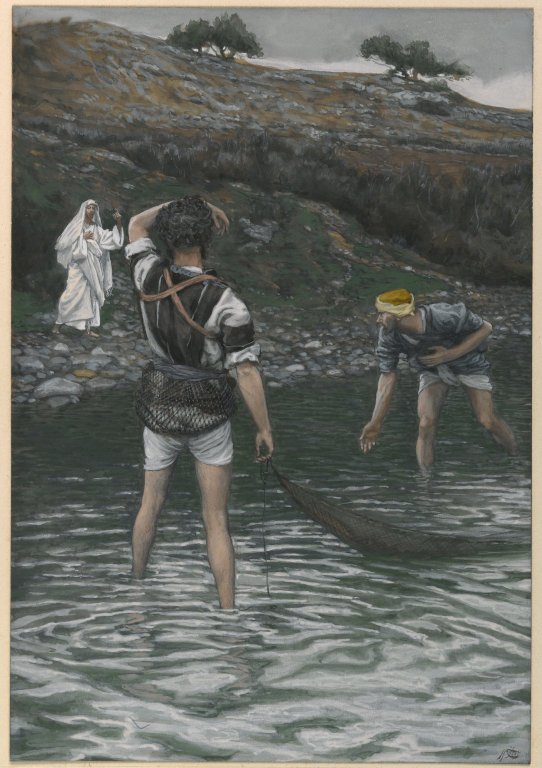

The worst of the stories was, “Where Are You Going And Where Have You Been,” by Joyce Carol Oates. I sat in the back of the room with my head bowed, hoping not to be called on the day we discussed that story. Not abnormal behavior for me, but that morning I was raw from reading about the teenage girl who opens her screen door and walks away with the devil. She knew who he was and he knew she knew. Can Jesus still get to her now? I didn’t want to say a word about this story because I was sure I’d been that girl. I was sure I’d be that girl again. I sat as still as I could and silently pleaded with Jesus to always have a stronger grip on me than the devil.

So I’m in my study carol, the one I always went to because if I leaned a smidgeon to the right I could see a sliver of the campus, and I decide to pretend that I am the valedictorian of my class. I would write an address to my fellow students to be given in the field house upon graduation. The idea was hilarious given my history of being a solid C student (give or take a minus), but it provided enough of a boost to my ego so that I wrote.

The paper was about how what we read should wake us up and shake us around. I argued that reading stories like the ones we read in Brown’s class is vital in forming who we are and how we ought to live. To this day that paper is one of my favorite things I’ve written.

And I think I fooled Dale Brown. He gave me an A on the paper. He wrote that he suspected my speech would be better then the “real” valedictorian address. He called me “one of those” students referring to the sort he’d never forget. He told me I was a writer.

Dale Brown helped me see myself differently. He helped me believe I might have the capability to wrestle with the tough stories. I can still see that girl, almost twenty years ago, leaning close to the words she’s trying to figure out, ignoring the gummy worms and the coffee that’s gone cold, in pain from trying to understand how to come back to life after seeing herself in the girl who walked with the devil, or the grandma in “A Good Man Is Hard To Find.”

Today, in order to get myself to write this piece for Relief, I’m pretending I’m giving Dale Brown’s eulogy. He died last year. He was riding his bike and swerved to avoid a car, but was knocked off and suffered injuries he couldn’t survive.

I’d prefer to pretend that he is still alive saving lives through his teaching; waking all of us up and helping us walk around the world with startled, awe-stricken eyes. I’d prefer to pretend that I am speaking at a banquet thanking him for his years of teaching. I’d prefer to pretend I am that girl twenty years ago, writing down that terrifying sentence about coming back to life, and waiting for Dale Brown to show me what that sentence means.

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:  The sun is snuggled still sleeping behind the mountains. He pulls their snowy peaks over his head and indulges in another hour of sleep. Not me, though. I’m awake. I’m out in public. I am caffeinated and somewhat functional. I am not necessarily in a bad mood. It's just a morning one. I am working the opening shift at the cafe. The sky is still dark.

The sun is snuggled still sleeping behind the mountains. He pulls their snowy peaks over his head and indulges in another hour of sleep. Not me, though. I’m awake. I’m out in public. I am caffeinated and somewhat functional. I am not necessarily in a bad mood. It's just a morning one. I am working the opening shift at the cafe. The sky is still dark. I tag along with my wife to her work functions, mingle with people whom I am trying desperately to assign names to faces. I get the question often enough. And it’s begun to rattle me like empty dinner glasses.

I tag along with my wife to her work functions, mingle with people whom I am trying desperately to assign names to faces. I get the question often enough. And it’s begun to rattle me like empty dinner glasses. On the second day of our impromptu beach vacation, Dennis decides to buy an electric planer at a local hardware store. “The oak panels need to be thinner, so they will resonate more once the harp is complete.”

On the second day of our impromptu beach vacation, Dennis decides to buy an electric planer at a local hardware store. “The oak panels need to be thinner, so they will resonate more once the harp is complete.” Just last week, during prayers at bedtime, my youngest son thanked God that piano lessons were over for the summer. I’m not sure when it became law for upright pianos to be stationed in every household, to break the backs of the fathers who move them there and to break the minds of children who, coming home daily from school, find not freedom but piano lessons, but it’s a law I resent even as I continue to abide by it. In one corner we, too, have a breaking-down piano like a hulking mushroom.

Just last week, during prayers at bedtime, my youngest son thanked God that piano lessons were over for the summer. I’m not sure when it became law for upright pianos to be stationed in every household, to break the backs of the fathers who move them there and to break the minds of children who, coming home daily from school, find not freedom but piano lessons, but it’s a law I resent even as I continue to abide by it. In one corner we, too, have a breaking-down piano like a hulking mushroom. The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s

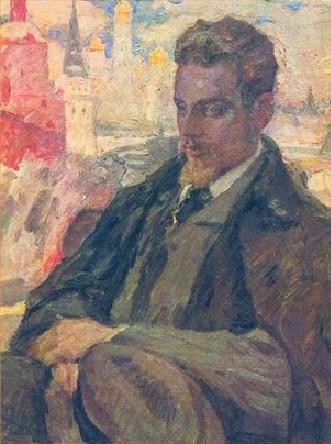

The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s  Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his

Sometimes, when I’m burnt out, I look to Rilke. Not his