Things

Chrysta Brown

On August 30, Kanye West won an award for being a brilliant artist of some sort. During his acceptance speech he claimed that awards shows were ridiculous, called himself an artist’s messiah, confessed to smoking pot, and announced that he would be running for president. A year ago, maybe even a month ago, I might have sighed and muttered, “Oh, Kanye,” but this time, with the nagging realization that I probably have more deadlines than talent, all I could do was think about how I will never be able to write like that and have people support it. Everything felt so meaningless.

There is a picture of Idris Elba saved on my computer. His hands are folded and he wears an expression that quite attractively blends judgment and concern. “Shouldn’t you be writing?” the caption asks. Yes. Yes, Idris, I should be writing. I should be penning down my every thought, victory, tragedy, and curiosity on paper and online, but the blank page and I are in the midst of a staring contest, and so neither one of us has much to say.

That may not be exactly true. There are a lot of things going on that would make excellent essays, or at least mediocre essays that I could edit into readable ones, but I don’t feel like talking about those things. It doesn’t matter, though. The lack of something to say and the lack of will to say something both yield the same result. Nothing. Yet, I’m still suffering from the urge to create. In spite of the fact that millions of thoughts get published and posted every minute of every day, I have the tiniest bit of hope that I can water and nurture and grow something special where nothing used to be.

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” God introduces himself as a character by speaking light, ecosystems, and cows into existence. I know what the Bible says. I know what the lesson is for the artist: Words have power. I guess that is true. Words do things, change things, create and destroy things. But, is the inverse also true? Is the artist powerless when he can’t find the words or when he isn’t big enough to speak them? It feels that way. I feel drained and empty when I sit down to write and all I can do is stare out of the open window and watch the trees let go of leaves that weren’t strong enough to keep trying.

The first sentence of the Bible does not interest me because I do not understand people who always have something to say. I do not trust people who brag about how easy creation is. What grabs me is second sentence. I like the part where the narrator reveals with a sort of flyaway detail that, prior to everything, there was a whole lot of nothing. If I were given this manuscript in a workshop, this is the part I would circle and highlight as the big point. As both a reader and a writer, I would ask the author, “How long did you stare at nothing before you found something to say?”

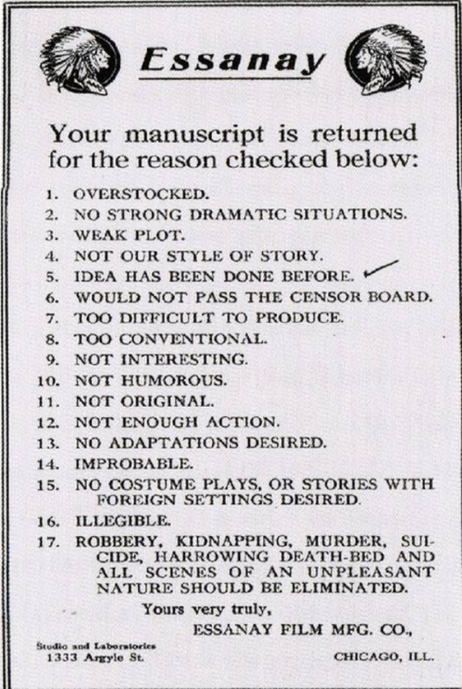

Rejection always hurts, but this publisher seems particularly hard to please! This vintage rejection slip is from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company (1907-1925), who is famous for their production of Charlie Chaplin movies (Photo originally posted on

Rejection always hurts, but this publisher seems particularly hard to please! This vintage rejection slip is from the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company (1907-1925), who is famous for their production of Charlie Chaplin movies (Photo originally posted on