“Mrs. Feyen, do you like professional football teams?” This comes from George, one of my 8th grade students. He’s asking me about football because I’m wearing a Notre Dame t-shirt today. I probably shouldn’t be wearing it; it’s not very professional, but every so often I get dreadfully homesick for the Midwest and this morning as I got dressed I decided to pull Notre Dame over my head and feel a little of South Bend on me as I walked through the day.

“Mrs. Feyen, do you like professional football teams?” This comes from George, one of my 8th grade students. He’s asking me about football because I’m wearing a Notre Dame t-shirt today. I probably shouldn’t be wearing it; it’s not very professional, but every so often I get dreadfully homesick for the Midwest and this morning as I got dressed I decided to pull Notre Dame over my head and feel a little of South Bend on me as I walked through the day.

I wore a cardigan and a scarf with it and figured nobody would notice I was wearing a t-shirt. George notices, and now he’s asking me about the NFL. While I like everything that has to do with football: tailgating, the stadiums, fall, old, grey depressed towns that transform into vibrant, storybook places for 48 hours, I know nothing about the sport, professional or college.

“Let me guess,” George says, shifting his backpack to his other shoulder. “The Chicago Bears.”

I smile. I never hear them referred to as “The Chicago Bears.” Just, “the Bears,” and the “s” is drawn out a bit. George reminds me where I am – in Maryland, in Redskin territory, in a classroom of 21 of the rowdiest, craziest, 8th graders I’ve ever come into contact with. Trying to teach them is like trying to keep the lids on 21 pots of boiling water. On better days, I call them hippogriffs. On the days they bring me to my knees, they are grizzly bears.

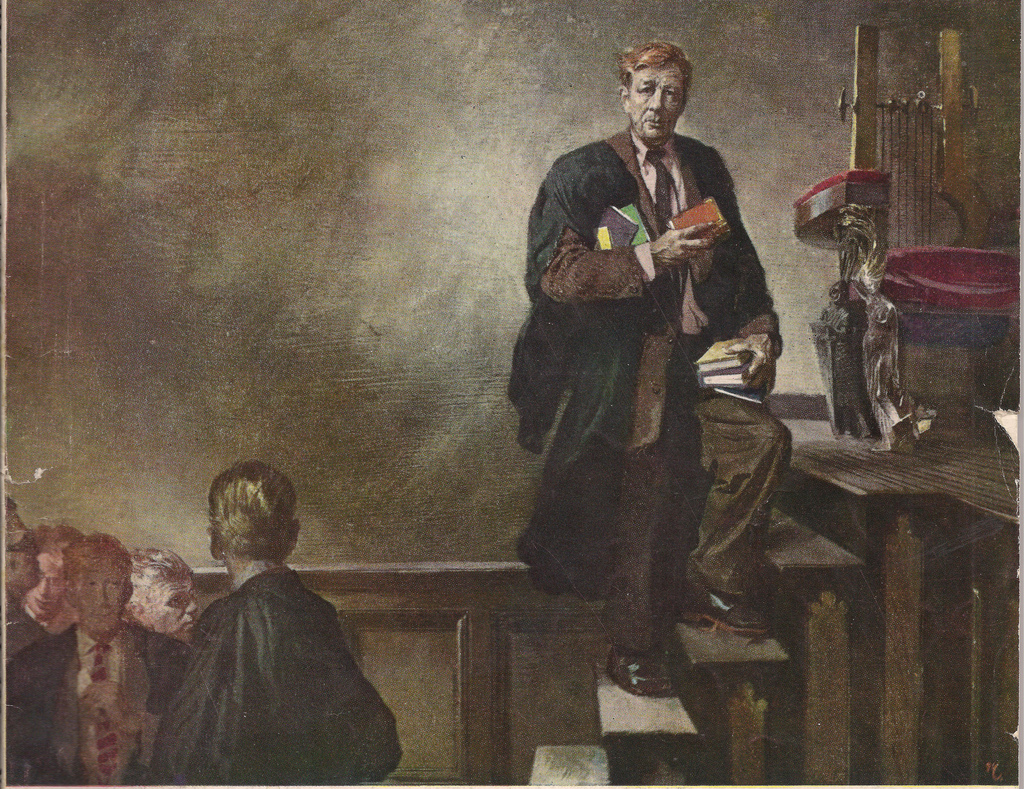

I shouldn’t take any of this personally: the eye rolls, the snickers, the talking while I’m talking. Most days, standing in front of them feels like I have my fly unzipped or toilet paper hanging from my butt. That’s how they look at me, if they look at me. Most of the time they are either looking at each other, falling asleep, or so zoned out I think I am teaching the dead. I usually drive home from school crying, trying to figure out where I went wrong.

They are my grizzly bears, though. As ruthless, conniving, and ridiculous as they are, I adore them. They make me laugh, they are dead silent when I read out loud to them, and when I can get them to trust me and themselves, they are poets. We take walks in a patch of woods behind the school and they write in the second person using all five senses. They can write a sonnet about baseball or their little brothers, all in iambic pentameter. Their writing is vulnerable and gritty. They can be lyrical and they can be stark. You’d never see it in class, though. It only comes out on paper, when they are writing with the lights off. Their preference. They are most comfortable in the dark.

“George,” I say as I erase the whiteboard. “I don’t think I can say I like the Bears, but I do root for them.” I turn towards him and say, “they break a lot of peoples’ hearts on Sundays in the fall.”

George laughs. “Yeah.” He leaves the classroom and I am by myself, looking around. Candy wrappers are everywhere. Assignments I took hours grading are balled up and lying next to the garbage can. There’s writing on the whiteboard, something about peaches. I think it’s a dirty, menacing joke aimed at a student in the class, but I’m not certain. I’m also not sure which student this is aimed at, nor am I sure how this got here in the first place. How did I not see a kid writing on the whiteboard?

As much as these students break my heart, I am addicted to the contrast they bring. I believe my faith lives in that contrast.

We are studying Romeo and Juliet right now, and day they meet Sampson and Gregory, they gasp in what I’m certain is delight when they hear Sampson talking about thrusting women against walls. When we get to the part where Gregory and Sampson contemplate the size and beauty of their reproductive organs, I feel like I’m conducting class in a frat house.

“I had NO IDEA how dirty this play is,” one kids says, delightedly.

When Romeo describes his love of Rosaline, “feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire, sick health,” we discuss why the opposites contribute to the definition of Romeo’s love. “You can feel it more,” one of them says.

We try to do the same thing to describe the word, “crush:” perfect confusion, sorrowful happiness, paralyzing giddiness. They all smile, and I smile, too. I remember so well those days.

“Romeo kind of likes this mood, doesn’t he?” I suggest.

“Yeah,” they all say, knowingly.

“Now you try,” I tell them, handing them a piece of paper.

Loud secret is used for "mysterious," blurry focus for "art," and my favorite, hopeful mystery for the word "bless."

I tell them I’m going to cry for how good they are. “Read mine! Read mine!” they say, reaching their papers towards me. I take their work, and they put their heads on the table, shy now. I always tell them good job. I always tell them I love what they write. It’s as close as I can get to saying I love them.

When Mercutio and Tybalt die, I have them make webs around their names and we write down all the things they were: inappropriate, angry, possessive, rude.

“Is that all they were?”

No, they say. Mercutio was hilarious and he was a good friend. Tybalt was fiercely protective of Juliet.

I tell them Mercutio and Tybalt were nasty and awful, but that’s not all they were. “If we believe they were made in the image of God, then nothing they do – nothing anything any of us do – can separate us from His love.” I stagger when I say this. I’m always stuttering and tripping over my feet when I talk to my 8th graders.

This class might give me nightmares. They might make me second guess everything I do, but they show me how to live in the contrast. I think it’s where the smiles are bigger, the laughter is heartier, and grace is at its most palpable.

We are cleaning up the classroom during the last five minutes of class. I’m trying to pass back papers, and kids are shooting baskets across the room with them. I get hit several times and realize they’re probably aiming at me. One girl has hip pinned another girl to the wall. Another kid is doing some sort of rendition of “Bring in the Noise, Bring in the Funk.”

George is sitting at his desk, whistling. He has perfect pitch, and I can hear him above all the ruckus. He is whistling the Doxology. “Praise God from whom all blessings flow.”

George reminds me where I am. George reminds me of my blessings. George, and all his classmates, help me believe in the hopeful mystery.

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nothing Gold Can Stay On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

“Mrs. Feyen, do you like professional football teams?” This comes from George, one of my 8th grade students. He’s asking me about football because I’m wearing a Notre Dame t-shirt today. I probably shouldn’t be wearing it; it’s not very professional, but every so often I get dreadfully homesick for the Midwest and this morning as I got dressed I decided to pull Notre Dame over my head and feel a little of South Bend on me as I walked through the day.

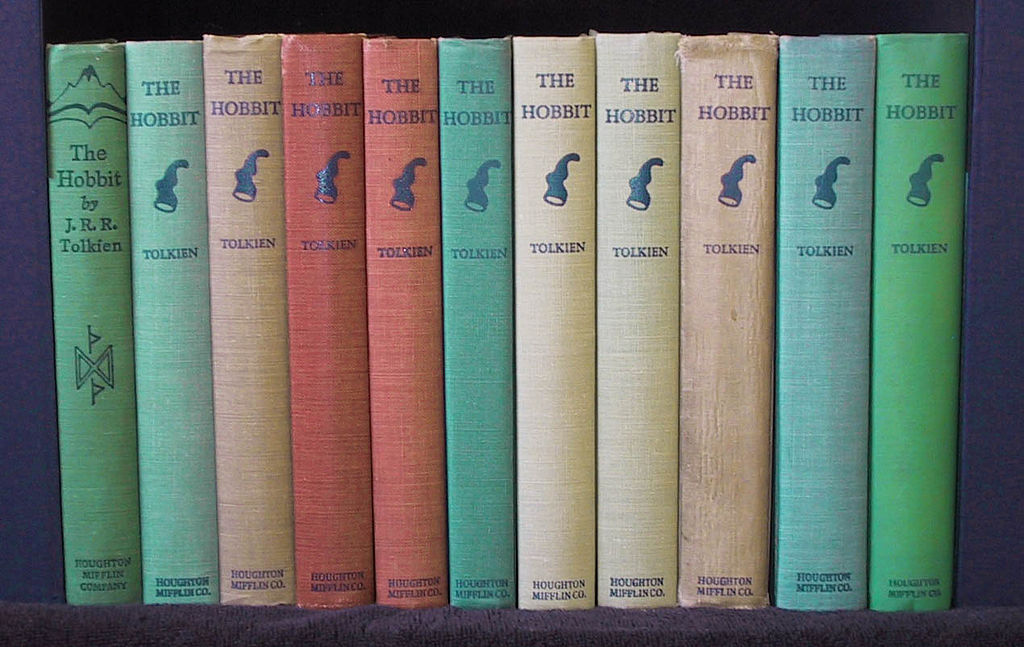

“Mrs. Feyen, do you like professional football teams?” This comes from George, one of my 8th grade students. He’s asking me about football because I’m wearing a Notre Dame t-shirt today. I probably shouldn’t be wearing it; it’s not very professional, but every so often I get dreadfully homesick for the Midwest and this morning as I got dressed I decided to pull Notre Dame over my head and feel a little of South Bend on me as I walked through the day. I am reading

I am reading