Cue the Fairy Tale Characters, Please

Jill Reid

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

Symbols are powerful. Even sticky old wigs have their magic, and in retrospect, the season of the Snow White wig was thick with both fairy tale and curse. Disney’s Rapunzel and Sleeping Beauty and Snow White played on loops on the living room TV, their Technicolor endings a crescendo of orchestra music, ball gowns, and satisfying conclusion. Meanwhile, I re-read passages for literature classes in which the dragon killed Beowulf, and Othello murdered Desdemona. Mr. Hyde overcame Dr. Jekyll, and poor tentative Alfred J. Prufrock measured out his “life in coffee spoons.”

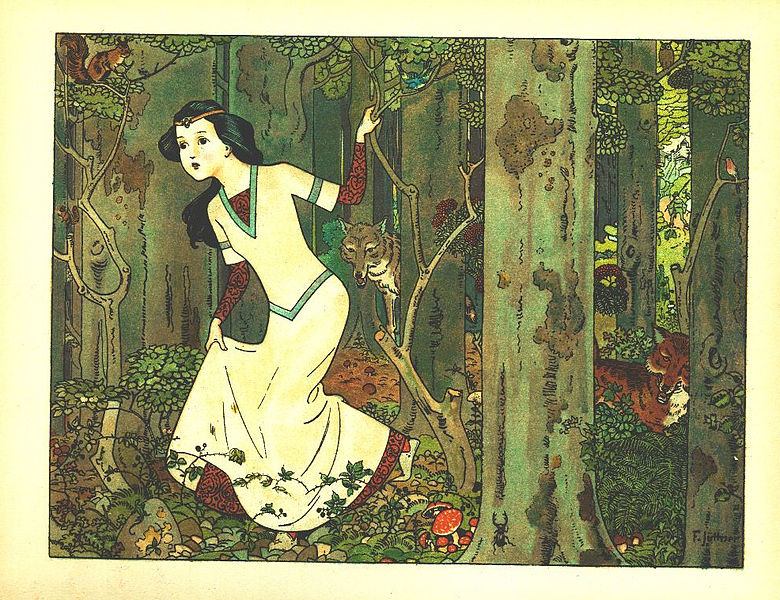

Those stories, in contrast to the fairy tale, were as fragmented as the world my child and I lived within. During the season of the Snow White wig, my own life experience with single parenthood, toddler potty training, and exhaustion dug in its heels against the “simplicity” of fairy tales. Really, how do you embrace the enchantment in Snow White’s story, when what you have read and lived and survived suggests that in your own story, should you ever bite into one of life’s poison apple, you will have to drive your own poisoned self to the ER?

That was also the season when, in the middle of a week sopping with the weariness of cynicism, my notebook became a revelation. I sat at my desk writing the word “Loss” over and over without even realizing the path my pen was taking. And next to that, I jotted down a statement by C.S. Lewis that, prior to that moment, had existed only as a lovely sentiment I intended to quote to students.

“Loss. Loss. Loss,” my notebook read. "Some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again,” C.S. Lewis told me. And just like that, after months of rolling my eyes at Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, I saw the wisdom in Ellie’s beautiful, tangled Snow White wig. “What,” I could almost hear Snow White whisper, “has ever been easy about overcoming a curse?”

Perhaps when C.S. Lewis talks about growing old enough to read fairytales again, he alludes to the slowly re-gained wisdom in believing in the possibility of the cursed truly overcoming their curses - even on this side of heaven. Rather than a curse that divvies itself out over a lifetime in wrinkles and mortgage payments, the fairy tale offers one pure cup of concentrated curse, potent as Snow White’s apple, for us to swallow and overcome all at once. There is a special kind of relief in knowing exactly what curse you’re up against , how to defeat it, and that it can be defeated at all.

Of fairy tales, Neil Gaiman, in a paragraph of G.K. Chesterton’s longer explanation, wrote, “Fairy tales are more than true; not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.” Each day, the dragons gather. They show up in the latest news cycle. They loom when I sit down to pay the bills or comfort a sick child. In class, I spend hours discussing all the gray spaces where the heroes fall to dragons or where, sometimes, there are no heroes at all. But, as I grow older, I believe more and more that in a world full of dragons, there is a special wisdom in embracing the fairy tale, matted and familiar as a Snow White wig, as a place of empowerment, where we can, at least for the breadth of a story, watch the dragons fall.

Read

Read