Returning

Joanna Campbell

My brother-in-law died on Thanksgiving. His death took him away from a suffering that began, in truth, the day his wife died suddenly nine years ago. His wife’s death did not mark a tragic beginning. It was a bookend holding up decades pressed against the day his father drowned trying to save his life in the Spring River.

My brother-in-law died on Thanksgiving. His death took him away from a suffering that began, in truth, the day his wife died suddenly nine years ago. His wife’s death did not mark a tragic beginning. It was a bookend holding up decades pressed against the day his father drowned trying to save his life in the Spring River.

The news about Mike stunned me for a moment, and then I breathed a little easier. Mike was free. The cancer didn’t get him. That was our biggest fear. Pneumonia eased him into a greater life unburdened by softball-sized tumors and excruciating pain. If vices exist in heaven, he can now drink without becoming an alcoholic. He can smoke without getting cancer. He is made whole. This is what I am to believe as a Christian. That’s good news in my tradition.

Here’s the problem. Now that he’s been relieved of his pain and angst, I’d like him returned back to us, whole and renewed. He’s been dead for over a week. That’s plenty of time to rest. In my book, he’s had a decent break from this messed up world and his broken body.

I never knew Mike before his wife died. I’m told he was a pillar of his community. I don’t need him to be a pillar. I wouldn’t mind if he returned in a cloud of cigarette smoke. I just want to see him restored, free of pain long buried in a riverbed. I need his stories, his expressions, his laughter, and music. I need him to be a brother to my husband and a father to my niece and an uncle to my husband’s children.

When my husband was fighting for his own life in a Seattle hospital a few years ago, I talked Mike out of driving 2,200 miles to break his brother out of ICU. I don’t doubt Mike’s conviction that his little brother was better off in his hands. Now my husband and I are released from our worries. We will no longer wonder about Mike’s mental and physical health. This trade-off feels like a bum deal.

The shape of my husband’s family is made by the endings of family members gone too soon.

I’ve known about death in the pot since I was little. My parents never shielded it from me. Mike’s death is different. It’s uncomfortably fresh. I feel such relief that he is no longer afflicted that I forget he’s dead. And then I remember. And it’s stunning.

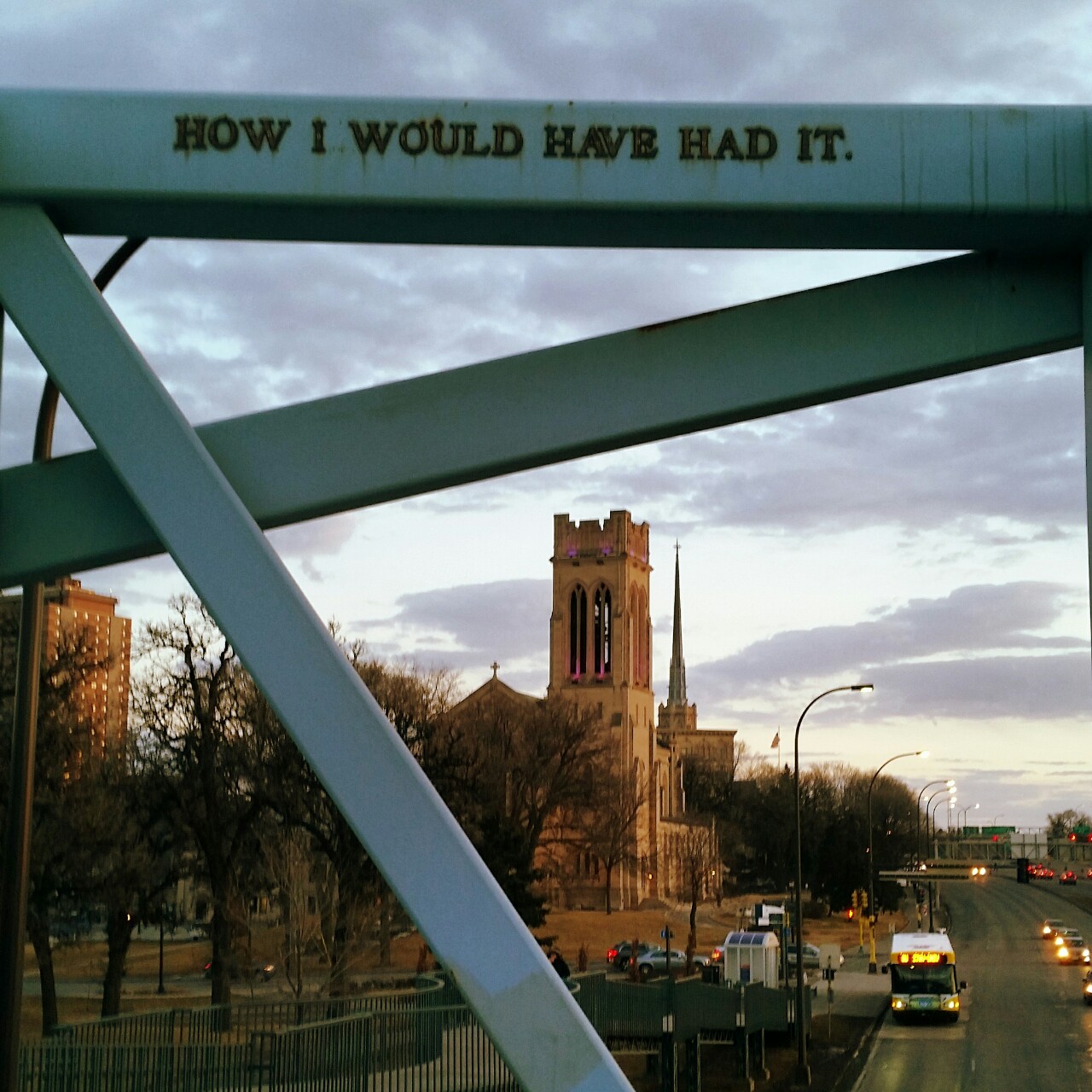

A sharp December wind strikes my face as I walk to church on this second Sunday in Advent. I am supposed to be preparing, literally and spiritually. I put my Advent wreath out a week late, and the center candle is missing. I can’t find it anywhere. I should be writing about snow globes and, instead, all I can think of is this ridiculous arrangement I’m forced to consent to. Mike is dead and will not return.

Each year, I celebrate the birth of Jesus without fail. I try, with little success, to block the holiday ads and treacle songs. I try to focus on the raw story of Mary and Joseph and a messy birth in a barn. I imagine what it must have been like to be part of such wonder. It’s hard for me to focus on newborn Jesus right now. I light two candles of my incomplete wreath. At least it has some greenery, I think. I feel selfish. I’m more focused on Mike and his body and spirit made whole so far from our reach.

I know this is magical thinking, wanting Mike to come back as if he’s been away at a cosmic rehab center. But it’s Advent. This is the time of waiting for the unexpected, the miraculous. I am trying my best to prepare, but I can’t even find the dang center candle on Amazon.com. Logic dictates Mike is not returning. This means we will never go fishing on his beloved St. Francis River, nor will he and my husband drink a tallboy in a backwater bar.

Maybe I don’t want what I’ve been taught, at least not right now. He is in a better place. True. That doesn’t change the gaping hole left in our family. It doesn’t alter the fact that my husband lost his only sibling. I don’t want tidy expressions of grief. They are too much like the holiday ads. I need the freedom to be messy in our tangled loss. I’ve got no choice but to wait in the muck and long for impossible things until the longing becomes part of an unforeseeable making. I need permission to want Mike back. He was my husband’s brother.

I find a broken white taper at the bottom of a moving box. It’ll do.