Doubting at Christmas

Jean Hoefling

![]() . . . But God himself, alive, pulling at the other end of the cord, perhaps approaching at an infinite speed, the hunter, King, husband— that is quite another matter.

—C.S. Lewis, Miracles

. . . But God himself, alive, pulling at the other end of the cord, perhaps approaching at an infinite speed, the hunter, King, husband— that is quite another matter.

—C.S. Lewis, Miracles

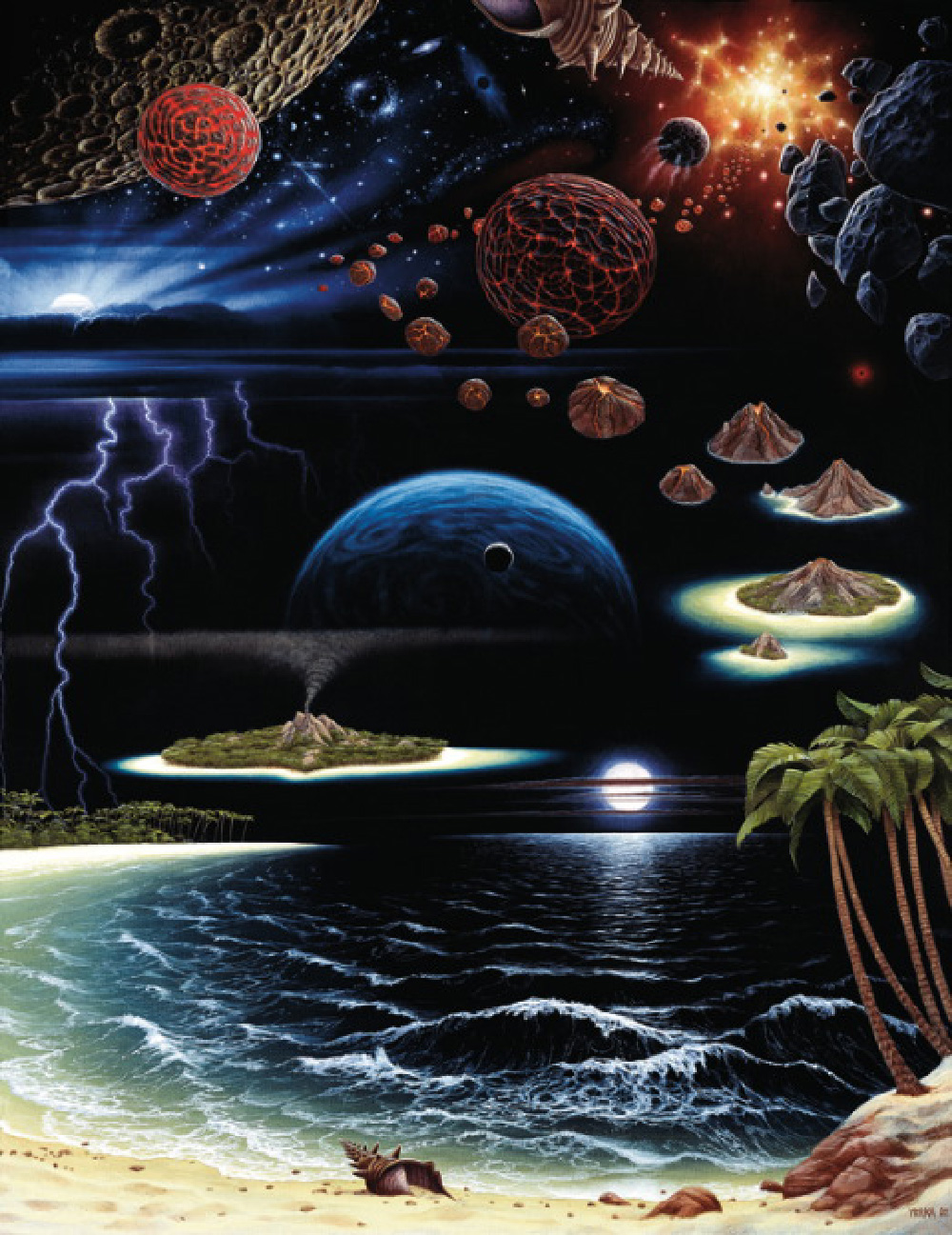

Christmas: God breaking the Second Law of Thermodynamics to snatch the cosmos from its ultimate decay. In other words, a miracle of upward mobility. The Orthodox icon of the Nativity teems with the theology and symbolism of this upswirl, this “redemption of the universe:” the ascending pull of light over the landscape; the bright celestials straddling the razor edge between time and eternity; the ethnic diversity of the Magi, God’s redemptive scope encompassing all peoples and all creation. And in the postures of Mary and Joseph we see the full gamut of human response to this event that couldn’t happen, yet did.

Here the figure of the Virgin is appropriately spacious and central. Mary casts her eyes not toward the babe but away from this one whose swaddling clothes and cradle resemble grave wrappings and a sarcophagus. Her restraint is a reminder, for who can look upon the face of God and live? Yet any minute Mary will pick up that normal looking baby and stare into omnipotent holiness, her soul taut with paradox. Mary’s power of belief is organic to who she is, a chemical and spiritual grace.

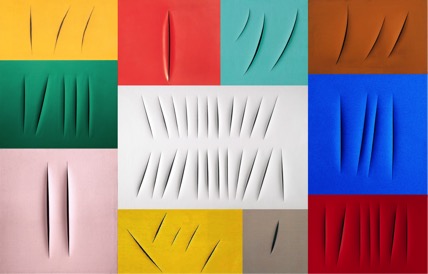

Yet in the figure of Joseph the Betrothed in the lower left we witness the other effect of miracle, the Church’s concession to the difficulty of grappling with blissfully mangled universal laws. A study in body language, Joseph slumps in the throes of mental torment, questioning the baby’s alleged origins. He’s under direct assault from Satan, come to once again sow his tedious doubts, this time in the guise of an aging shepherd. The shepherd’s short tunic and rigid profile symbolize duplicity and gross inadequacy—this father of lies who would keep Joseph’s eyes in the dust with no reference to the divine. (See: “Becoming Two-Eyed”)

In the battle to make peace with mystery, the human mind has a remarkable capacity to see blank sky where in fact shines a sight-giving star. The downward drag of psychic inertia is ever present here among the shambles of the Second Law. Yet though God may approach with “infinite speed,” his home is no longer a manger, but our embrace.