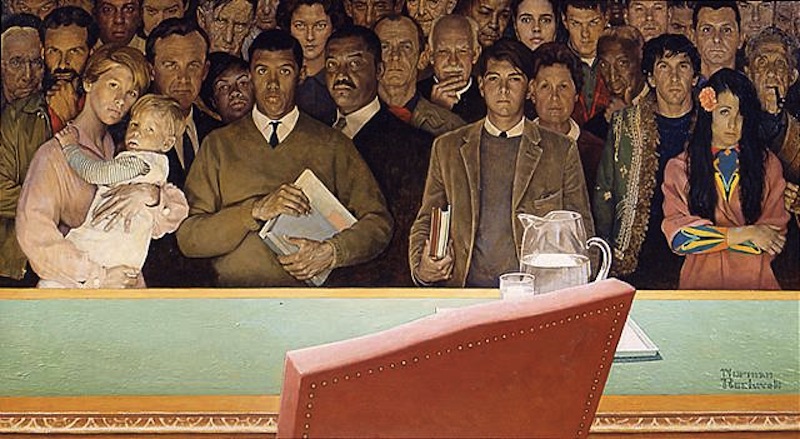

Mental Hygiene

Jean Hoefling

I’ve become mildly addicted to the campy, corny, classroom social guidance films of the post-war years. These social engineering gems portray the standards of an American society (albeit idealized) so long-gone it may as well be foreign. Yet partly through the philosophy portrayed in mental hygiene films, a couple of generations of American young people were indoctrinated (or not) on subjects as varied as personal grooming, sex education, Communism, and everybody’s Cold War favorite: surviving a nuclear blast with duck-and-cover techniques. In atonal, scripted voices, characters display religious commitment to “fitting in,”“cleanliness and neatness,”and the ominous mantra, “Girls who park in cars with boys are not really popular.” In What Makes a Good Party? there’s not a racy décolleté, beatnik individualist, or hint of postmodern cynicism among the swell teens gathered around the piano. One might wonder if the chaperoning mother contrasted this wholesome tableau with her own wild, Roaring Twenties youth. And me, I’m just a little bit wistful of the whole thing.

I ask myself why I keep watching. Though amateurish in the extreme by current standards, it’s the naiveté and unapologetic dogmatism of these films that draws me, which had to be partly what motivated the psychically fractured Cold War-era adults who produced and endorsed them –– determined that the new generation would enjoy the symmetrical lives they’d been deprived of through the Depression and horrors of war. Mental Hygiene author Ken Smith suggests too that post-war zealots might also have sought to exorcise their own internal demons through moral and social ideation. Cleanliness and neatness! If you kids would just keep those fingernails cleaner, maybe we’d be able to forget the waters that ran red on D-Day.

Sixty years later, our culture dodges its own specters. My children and their friends have been clawed to shreds by the wolves of cultural nihilism, and my numbed heart scans for easy answers, big colorful Band-Aids. I too crave security and order, social niceties, life without serial school shootings or restaurants full of men’s hairy armpits. Tonight, I’ll tune in to another tidy social guidance film, say, Arranging the Tea Table. If I can get that table squared away, maybe everything else will fall in place.