Smartwoods

Joanna Campbell

If I can see a tree outside my bedroom window, blood flow to my brain will be different than if I was looking at a view without vegetation. Right now, I have a rectangular perspective of deciduous trees and evergreens making their home next to sidewalks and steep neighborhood staircases. The Italian restaurant across the street is shaded by bare-branched trees adorned in twinkle lights. I have lived in Seattle, Washington, for four years, the most urban place I have ever called home. Wildness and development exist as two tangled lovers, bound by each other’s bodies. I came from Arkansas, and there was a forest in my backyard. I went to the woods as often as I could.

If I can see a tree outside my bedroom window, blood flow to my brain will be different than if I was looking at a view without vegetation. Right now, I have a rectangular perspective of deciduous trees and evergreens making their home next to sidewalks and steep neighborhood staircases. The Italian restaurant across the street is shaded by bare-branched trees adorned in twinkle lights. I have lived in Seattle, Washington, for four years, the most urban place I have ever called home. Wildness and development exist as two tangled lovers, bound by each other’s bodies. I came from Arkansas, and there was a forest in my backyard. I went to the woods as often as I could.

Nature is unscripted. There are no directors, writers, artists, activists, scientists, or programmers predetermining my experience. No one is cuing or staging events. I get to be surprised on nature’s terms, and with thousands of variables at play, the possibilities are limitless. In Seattle, this means a sea gull suddenly appears. Occasionally, a bald eagle will soar. I wonder about the village life of microorganisms dwelling in the rosemary bush that Chef Paul uses for his pasta dishes.

On clear days, I can see beyond the Italian restaurant and the undulating Seattle neighborhoods, all the way to Puget Sound and the Olympic mountains. Though I have never penetrated the heart of its wildness, glimpsing the glacial-capped mountains from my home perch offers its own kind of exhilaration. I know there are six species of shrews and four species of bats. There are flying squirrels, marmots, and Pacific jumping mice. Wolves and black bears, elk and porcupines and cougars are living somewhere in the folds of the land I see from my living room window. River otters share territory with both the spotted and the striped skunk. And those are just a handful of the mammals. Amphibians, reptiles, invertebrates, birds, and marine animals breathe the same air. There are six kinds of salamanders, four kinds of frogs, one toad, and one newt, the rough-skinned variety.

Yes, humans are part of nature. And, humans are influencing nature in terrifying ways. And yes, there are no longer any places on the planet untouched by anthropomorphic choices. We’ve altered the chemistry of the atmosphere after all. But still, I know that walking through my childhood forest is vastly different from using a painting or sketching app on an electronically-intelligent, handheld device. The toolbox on the iPad was decided for the “user” by someone else. The forest’s toolbox is up to your own imagination. You may decide the forest is a place for solitude, reflection, adventure, or escape. It may be a place to play, learn, draw, plant, crawl, climb, cry, laugh, or pretend. There is medicine. There is food. There is sanctuary. There are tools and potential tools. There is paint and clay. There are nuts and crystals and vines. There are bones and long branches dotted in lichen hamlets. All in the forest. All free.

The forest is not framed as a box. It did not arrive in a box. Imperfect spirals and curves and edges separate one thing from another. Nature lives and breathes. Smartphones are not vital organs. Swamps are the lungs of the Earth.

Though it’s possible to reduce ecological processes to precise scientific explanations, nature is miraculous just as human life is miraculous. It is no wonder I secretly hope trees may speak a human language. Or maybe the trees strain for us to hear them. The skin of the Earth and all the wild things thriving from its body are the souls keeping us alive, holding us, sheltering our sanity, giving us hope and inspiration to be more than users. We are creators. We are imagineers in ways most opposite to Disney’s brand of employment.

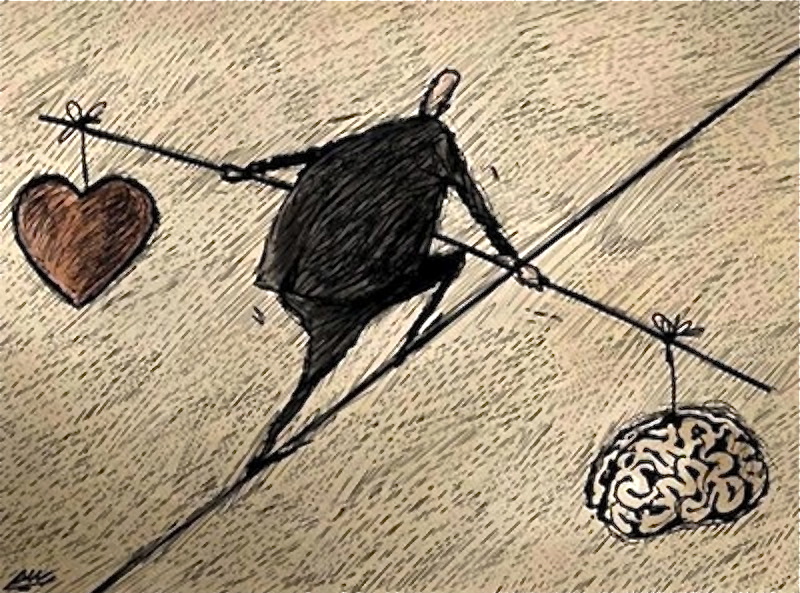

And here I am, writing this missive on my MacBook Air, created by a wildly imaginative person who loved art and calligraphy and beauty. I am listening to music on iTunes. It is an instrumental piece titled Become Ocean. I gaze at trees and buildings framed by 90-degree angles. The music calms and transports me away from the gray dark winter of Seattle. Given these ironies, I still know with all that I am that walking through the woods gives my heart delight unlike any cyber-styled comfort. No, delight is not a correct description. The euphoria of breathing without worry for what may happen, knowing something exquisite could transpire at any moment and a shimmering wave of endorphins will sparkle through the body—that’s the feeling. That’s the surprise I long for amidst the predetermined criteria of computer-generated beauty. Give me a fungus-infested tree over a perfect sequence of Fibonacci numbers, which produce the ideal pixelated tree. I want the freedom to not understand everything. My body needs mystery and mistakes.