The question, "Will there be stories in heaven?" became an issue for me only when my son was two or three and we started letting him watch a limited amount of TV. Now, this isn't a post about why we let our kid watch TV, even though that would likely get a lot of hits. This is about all these nonviolent alternatives to G.I. Joe and Transformers that are, frankly, dreadfully dull.

Take Caillou, which is maybe an extreme case but is for me the epitome of dull children's programming. Nothing happens! Even in shows I kinda like, such as My Big, Big Friend or Pinky Dinky Doo, nothing much really happens. It concerns me to think that somehow the violence is what makes the difference. It would be tantamount to saying that sin is necessary for interesting conflict and thus for narrative itself. And if that's true, and if one day all sin will be redeemed for good, then it's not clear what our lives will look like—what our very identities will consist in—without story.

I hope it's not strange to say our identities depend on story. Even God tells us who He is through stories in Scripture, and the primary way we know who Jesus himself is is through the stories of the Gospels. Can we imagine ourselves, purified, but without stories, especially without new stories?

Is there narrative without sin and the violence it entails? Most of our Bible stories presume it, even those about Christ. There's much to be said on the subject of violence/nonviolence in children's TV, but I want to focus on when narrative gets "interesting."

In the tedious plots of Caillou and shows like it, there is often no real moral dilemma and thus no real stakes. A child may care a little about whether Caillou makes it through his dentist appointment, but they won't care as much as they will about whether Wolverine defeats Juggernaut again. The stakes in the Wolverine battle are simply higher and so overcoming the conflict means more. It is important that Juggernaut is evil or wants to commit evil acts and that Wolverine is a force for good competent and powerful enough to counteract that evil.

My son even likes the villains. I have decided not to freak out about this. Villains are powerful, and for a time, anyway, they get to do more or less whatever they want. Their wants are, as with many sinful wants, pretty limited and kind of stupid—a fantasy of total freedom. For a kid, this is pretty attractive, even as it is also scary. You don't want Juggernaut or Magneto to get his way in everything, but you might like to get your own.

Of course, some Caillou plots are more staked than others. Going to the zoo is pretty boring, going to the dentist may actually be kind of interesting. It taps into our finitude and our fears of pain and illness and of the body torn or violated. Even an adult may be interested in how a child comes through a dentist appointment. The problem here really is something like ignorance, but more than this, it is about real risk, about something that is legitimately frightening.

A stake in a narrative conflict, then, isn't necessarily the same as a sin or the possibility of sin. It is some part of our understanding of ourselves as human beings that is put into question or to some test. Conflict in this sense does not require an active evil force to drive it.

But it's more complicated, still. The Christian understanding of evil denies that evil is a thing, anyway. We call evil that which falls short of or lacks the good. Our whole broken world is evil in this sense. Narratives about scaling mountains or getting trapped in ravines or being attacked by a bear are part of this kind of evil that is not active but is clearly not good.

The enlightened response to natural evil is to say that we misname it, that the world "is what it is" and we shouldn't moralize it. And it's true we tend to view the world solipsistically, as if the universe were designed for my personal benefit and must be somehow broken if I am not entirely content. However, it is possible to have faith that the (recreated) world can become a true home for humans generally without requiring that it meet all my desires individually, in which case this world is still not what it could be—or I am not yet all I could be.

So let's imagine a revised creation in which humans have access to what they need not only to survive but to thrive (which may already be the case) and where we live so in the light of God's glory that we not only clearly perceive the good but also understand how desirable it is and pursue it joyfully and eagerly (which is emphatically not the case). Can we imagine narrative conflict here?

I think we must still, at least, have the old stories. If we remain in any way finite, which is to say, still human, though living eternally, then we will still need stories to make sense of things with our limited brains. Perhaps stories will be like little breaks from the reality of God rather than glimpses of it. And perhaps hearing the stories of people who erred and had to be brought back may inspire some occasional poor souls to rebel in their little way—the stories would still be open to bad interpretations, after all.

But if we continue to develop the gifts we've been given in meaningful work and relationships, then we will still desire things, and we will still find parts of the world resisting or creating obstacles to that desire, and these will be the seeds of new narratives. Desire, in a world that is not merely there for my benefit, only indicates the ability to imagine something more, and for a finite creature with an infinite soul, we can always imagine something more.

The possibility of narrative in eternity depends in a real way on the doctrine of God's abundance. If God is infinite and his creation is infinitely abundant, then finite creatures cannot cease to find new adventures in exploration and discovery of this abundance.

I'm not sure this is entirely satisfying, though it's the best I've got for the time being. It may be that I am still too broken to appreciate how satisfying narratives of discovering God's goodness could be when my and others' understandings and hearts have been perfected at last. I only have the current stories to go on, and perhaps 90% of the time I find them intolerably naive and egotistical. There's too much darkness in me to have much patience with easy narratives of encountering the light. But that 10% of the time when it works for me, well, then I feel a profound compulsion toward the light, a deep desire for my own story to end that way, at least some times, and this desire seems beyond reproach, even essential. Whatever happens in eternity, we can have no stories here without that desire to find our hearts' true home.

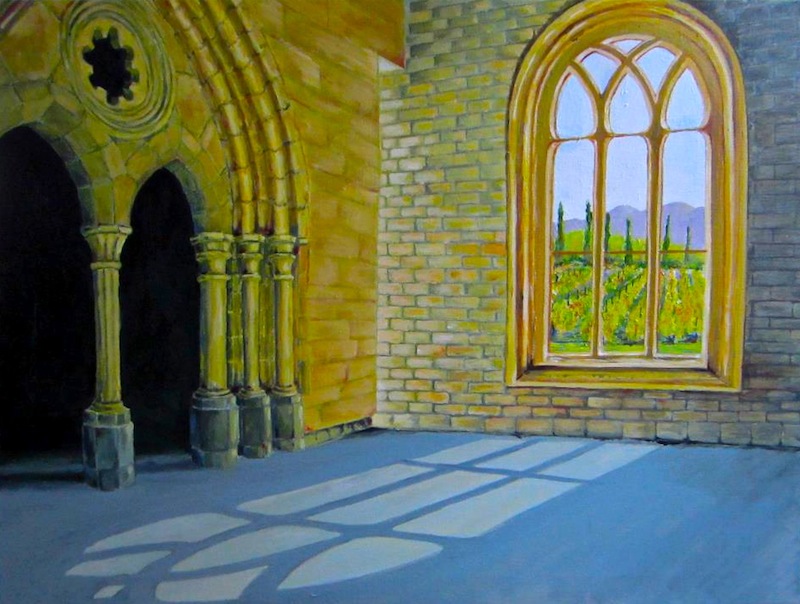

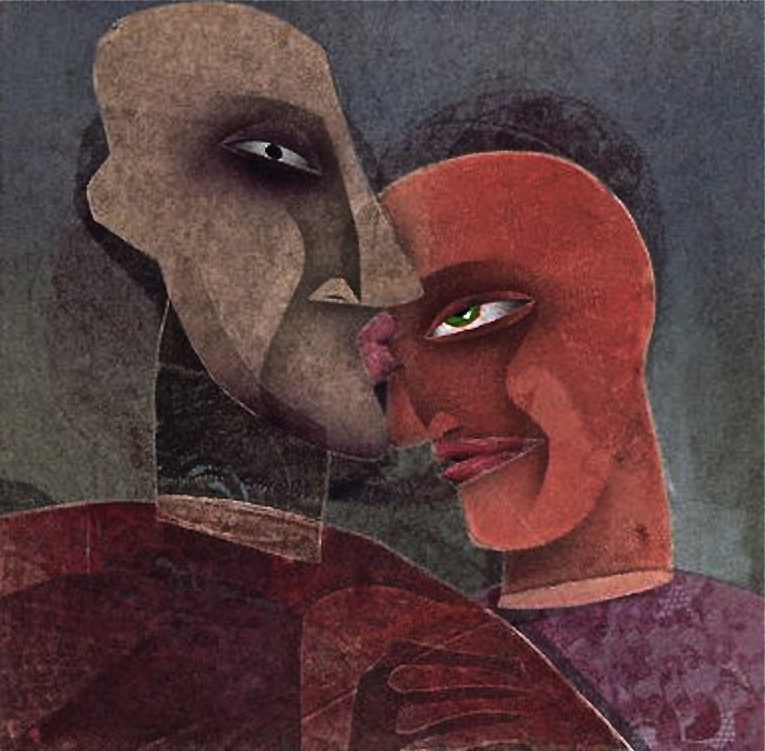

(Painting by N. C. Wyeth)